Mr. TN Seshan’s tenure as Election Commissioner (12 December 1990 to 11 December 1996) changed how we Indians viewed elections—he made free and fair polls a public expectation rather than an exception. The revolution he brought about was to enforce the Rules, provisions and systems that already existed, but no EC before him had acted sufficiently on. The Model Code of Conduct for instance, which political parties routinely flouted, with EC looking in the other direction. He cancelled or postponed elections where the MCC was blatantly violated. He took action to drastically reduce booth capturing, and clean up electoral rolls and reduce bogus voting. He made candidates and parties accountable for their campaign spending and took strong action against black money in elections. He strengthened monitoring of polling stations, and deployed paramilitary forces in sensitive areas. He laid the ground for Voter ID cards. He increased transparency by publishing election schedules and guidelines well in advance.

The man who ‘ate politicians for breakfast’ helped strengthen and deepen Indian democracy.

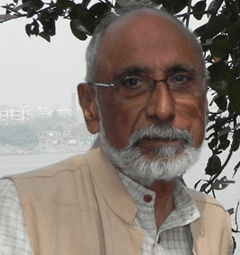

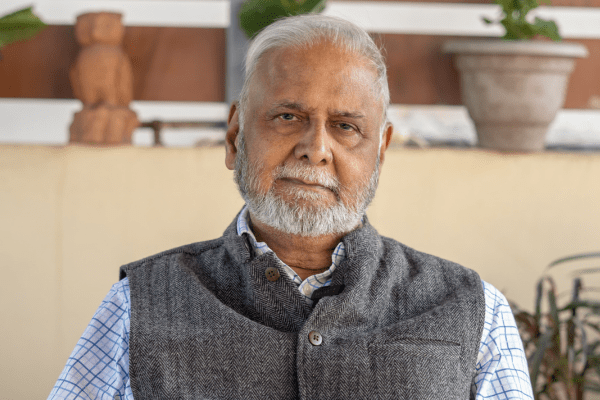

If Mr. Seshan brought about all these changes through rigorously using his given power as a bureaucrat, Jagdeep Chhokar, did it purely from the outside. He co-founded the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) in 1999 along with his colleague Prof Trilochan Sastry and others as an NGO.

ADR’s primary mission is to improve governance and strengthen democracy by bringing transparency and accountability into India’s political and electoral processes. Over the past two decades, it has become one of the most credible civil society voices on issues of electoral reforms, political funding, and the integrity of candidates and parties.

One can see echoes of Mr. Seshan’s work–one of ADR’s most significant contributions has been its role in disclosure of criminal, financial, and educational background of candidates contesting elections. Following a landmark Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed by ADR, the Supreme Court of India in 2002 mandated that all candidates must file self-sworn affidavits disclosing their criminal records, assets, liabilities, and educational qualifications. This judgment fundamentally changed the way Indian voters access information about their representatives. Since then, ADR, through its platform MyNeta.info, has been collecting, analyzing, and disseminating this information for every state and national election, enabling citizens to make more informed choices.

ADR has also been active in examining political party funding and expenditure, a highly opaque area of Indian democracy. By studying income tax returns and donation reports of political parties, it has consistently highlighted the growing role of unaccounted money in politics. ADR’s reports show that a large proportion of party funding comes from unknown sources, often via electoral bonds or cash donations, which raises concerns about transparency. These findings have been widely cited in media, parliamentary debates, and reform discussions.

Beyond data disclosure, ADR has worked to strengthen electoral reforms in collaboration with the Election Commission of India (ECI), civil society organizations, and policy experts. Its advocacy has covered areas such as decriminalization of politics, regulation of inner-party democracy, curbing misuse of money and muscle power, and improving voter awareness.

Another major initiative is citizen empowerment through voter education. ADR conducts voter awareness campaigns, disseminates easy-to-understand report cards on candidates, and organizes debates and dialogues to promote ethical voting. It also collaborates with other organizations on programs like the National Election Watch (NEW), a network that monitors elections and promotes democratic accountability.

ADR has been central in challenging the electoral bond scheme in courts. In February 2024, the Supreme Court of India struck down the electoral bond scheme as unconstitutional, ordering disclosure of donor identities, amounts, etc.

In essence, ADR’s work has created a data-driven framework for citizen engagement, holding both candidates and political parties accountable. While challenges remain in implementing deeper reforms, ADR has significantly advanced transparency in Indian democracy and continues to push for systemic change.

Recent Initiatives of ADR

- ADR has published updated data (as of July 2025) on how parties redeemed electoral bonds from 2018-24, including comparison with State Bank of India RTI responses. Their analyses show that in FY 2022-23, 82.42% of the income from “unknown sources” declared by national political parties came from electoral bonds.

- The report also examines the financial disclosures of Registered Unrecognised Political Parties (those registered with the Election Commission but not recognised as state or national parties). There was a 223% rise in declared income during FY 2022-23 among these parties.

- ADR and its network National Election Watch (NEW) analysed the affidavits of 8,337 out of 8,360 candidates in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections

- Among findings:

• Around 20% of all candidates had declared criminal cases; for state party candidates it was ~47%.

• 46% of the winning MPs declared criminal cases, up from 43% in 2019.

A Friend

For Mamata and me however, he was Jagdeep, husband of colleague and dear friend Kiran. For me, he was also the colleague of my husband, and neighbour for decades.

What I recall very fondly is how caring of older people Jagdeep and Kiran were. Often when my parents were visiting and they knew I was travelling, they would ensure to drop in and chat, and solve any little problem they might have. The affection was mutual. He was a particular favourite of my mother’s who would rush to make rasam if she heard he had a cold.

Jagdeep did his Law when he was teaching at IIM. And he never did well in exams at all, because he did not follow the quarter-baked kunjis from which examiners expected students to mug and regurgitate answers. He would regale us with the regressive and misinterpreted answers that featured in crib-books, and while we laughed, we also worried about what lawyers were learning.

All of us who knew Jagdeep personally will of course miss you. But the whole country will miss you. Thank you for everything you have done for India’s democracy. We know it was your consuming passion and commitment for the last 25 years. And we also know it took an immense amount of courage.

Thank you Jagdeep. RIP.

Wish you all strength, Kiran.

–Meena and Mamata

Also see: Close encouters with Al-Seshan at https://millennialmatriarch464992105.wordpress.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=1106&action=edit