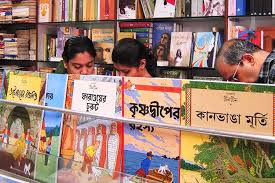

Just as the winter season of book fairs and literature festivals around the country was coming to a close, the temperature heated up with an article in a British newspaper that alleged that the hundred or more literature festivals that covered all parts of the country were more about “being seen” rather than a serious love for books and reading. The article unleashed a flurry of responses, rejoinders and rebuttals. And the debate may continue until the next literature festival.

While the somewhat glitzy avatar of literature festivals might be relatively recent, it may be a surprise to discover that book fairs have a long history in India, and have always had a substantial attendance. In fact, the first book fair in India was held in 1918 in Calcutta. The Boi Mela as it was called, was held at College Street, the hub of Bengal’s learning and publishing industry. This was not a society event, although it was certainly helmed by some of the most prominent intellectuals of the day in Bengal including Rabindranath Tagore, Lala Lajpat Rai, Gurudas Banerjee, Bepinchandra Pal, and Aurobindo Ghosh, among others.

The Book Exhibition, as it was called, was one of the activities that were being planned and carried out as part of the nationwide wave of Swadeshi. The Swadeshi Movement is largely associated with Gandhiji who gave the call for boycott of British goods and adoption of hand-spun khadi as part of the Non-Cooperation Movement launched in 1920-21. However, the swadeshi movement had its roots much before that, in response to the British plan to bifurcate Bengal in 1905. In August 1905, a massive meeting was held at Calcutta Town hall where the formal declaration of the Swadeshi Movement was made. There was a call to boycott Manchester cloth and Liverpool salt. The formal partition of Bengal in 1905 strengthened the call, and the involvement of people from all walks of life in boycotting all British goods and services. The people were fired by the patriotic songs composed by Rabindranath Tagore.

Another aspect of this movement was to counter the education policies of the British Government by evolving a nationalist education system. This triggered a demand for a national university. By November 1905 the climate was charged with multi-pronged efforts towards this. Speeches, meetings, articles in newspapers and magazines endorsed the idea of a national university. Prominent citizens gave generous donations for its establishment. At a conference held on 16 November 1905, a resolution was passed to “establish a National Council of Education… to organize a system of education — Literary, Scientific and Technical on National Lines and under National Control”. The process to work out the details took four months. A resolution formalizing this was passed on 11 March 1906.The Council’s prime objective was to “quicken the national life of the people.”

The National Council of Education (NCE) started the movement to spread science and technical education on national lines and under national control, to counter education and trade policies of the British government. On 14 August 1906, the Council’s first academic institute was inaugurated. This was the Bengal National College and School. Subsequently it also established the Bengal Technical Institute; both of which would later merge to form Jadavpur University.

This was several years before Gandhiji launched his nationwide stir for Swadeshi and set up the first Rashtriya Shala in 1920 to promote national education, manual labour, and handmade products.

Aurobindo Ghosh was the first Principal of Bengal National College. In an article published in 1908 he wrote: ‘The Council is not merely an educational body nor is the College merely an educational institution; they are trustees to the people of a great instrument of National regeneration and should always work in that spirit.’ The founding members also felt that there was a need for widening education and people’s access to books.

It was in this spirit that NCE organized what is considered to be India’s first book fair in 1918. This event symbolized self-reliance and intellectual independence which was one aspect of the Swadeshi Movement. All the leading publishers of that time took part. The Book Exhibition, as it was then called, generated a lot of interest among citizens. It continued to be held annually for the next few years till the nationalist movement shifted its focus to a greater struggle against the British rule.

Over time memories of the first book fair slipped into oblivion until the 1970s when a group of young book lovers and publishers of Kolkata who met regularly at the College Street Coffee House started discussing how the publishing trade could be boosted. Someone gave the example of the Frankfurt Book Fair a commercial trade fair of books. The young publishers envisaged that a similar event could be held in Kolkata, but the older publishers were wary and skeptical about such an event. They felt that books were not commodities that could be sold in fairs. The younger group persisted and their efforts bore fruit when the first Kolkata Book Fair was organized on 5 March 1976. 34 publishers participated and 56 stalls were set up near Victoria Memorial. The entry fee was a nominal 50 paise. Book lovers flocked in.

By 1983, the Fair achieved international accreditation and attracted larger and larger crowds. It moved to the larger Maidan grounds to accommodate growing participation of publishers as well as visitors. Despite challenges like the devastating fire of 1997, which destroyed 100,000 books, and rain damage the following year, the Fair’s resilience became its hallmark.

From 1991, the Fair introduced a focal theme every year, on the lines of the Frankfurt Book Fair. Each year one Indian state was selected to be the theme state for that year’s Fair, highlighting the literature and culture of the state. The first theme state was Assam. Subsequently foreign countries were also accorded theme status for each year. From 1997, the focal theme has been a foreign country, starting with France.

In 2018 the centenary of the first Book Fair was celebrated with a modest book exhibition organized by the Jadavpur campus of National Council of Education.

Starting as a 10-day event, the Kolkata Book Fair gradually became a 12-day affair, usually starting in last week of January. Today the Boi Mela as it is locally called occupies as important a space in the calendar of Bengalis as does Durga Puja. It epitomizes the vibrant intellectual culture, and celebrates Kolkata’s history of reading, learning and sharing knowledge. It is also a reminder of the legacy of the Book Fair, a common meeting place for bibliophiles from every walk of life.

–Mamata