In India this is the time of year when “spring cleaning” takes place. In the run up to Diwali, homes are thoroughly aired, dusted and cleaned, and every nook and corner cleared of dirt and cobwebs. Just as this frenzy of cleaning activity has begun, I read a news item that in one of the most famous art museums in the world, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the cleaning crew had been given an order “No vacuum cleaners and no dusters”. They had been given special instructions not to clear, or even slightly disturb, a single cobweb inside the gallery for the last three months. In fact, the Museum Curator takes a round every week to check that all crevices and corners have adequate cobwebs!

This preparation has been the prelude to an exhibition titled “Clara and Crawly Creatures” which will open to the public from 30 September 2022. The exhibition explores how perceptions of insects in art and science have changed over the centuries. In the Middle Ages, lizards, insects, and spiders were associated with death, and with the devil in European culture, but the exhibition notes that in the 16th and 17th centuries there was a re-imagining of the role of insects after the microscope allowed artists and scientists to appreciate beauty that wasn’t always so obvious.

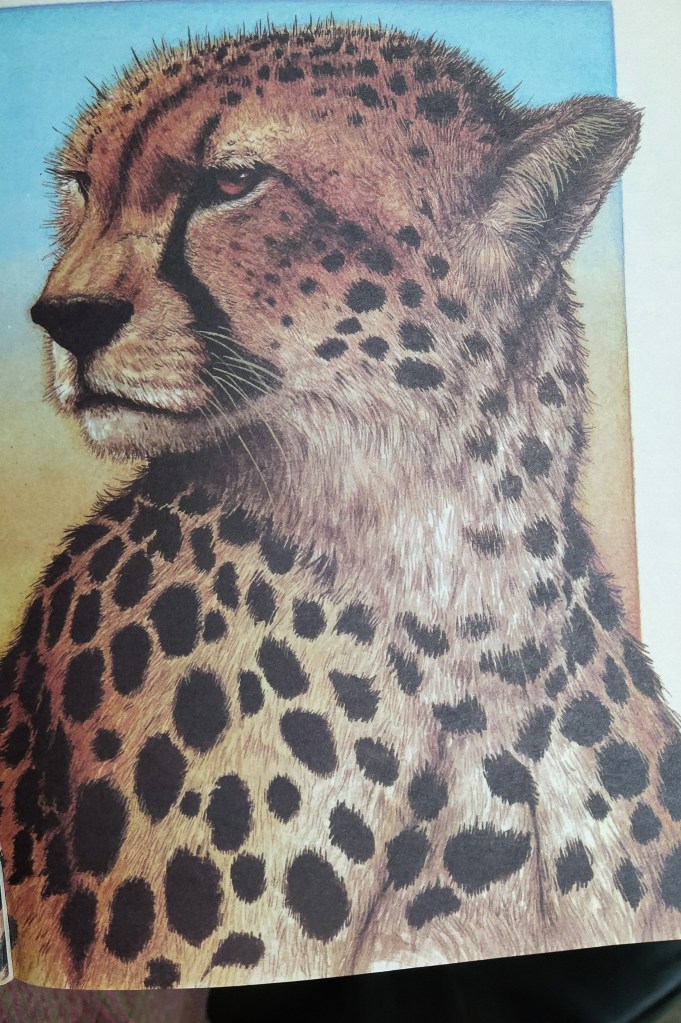

The exhibition prominently displays Albrecht Dürer’s 1505 painting of a stag beetle, its pincers raised. The exhibits take one through the history of how insects have been perceived over the centuries by artists and scientists who have been fascinated by the beauty and ingenuity of these small creatures. The culmination and the highlight of the exhibition is a dark room which has a huge installation by artist Tomas Saraceno– made from silk woven by four spider species that he houses in his studio in Berlin. In fact Saraceno emphasizes that it is not him, but the spiders who should be recognized as the artists.

Attention is also drawn to the uncleared cobwebs in the rest of the gallery by An Open Letter for Invertebrate Rights, written by Saraceno and placed next to one of the webs in which he makes a strong case for coexisting with creepy-crawlies rather than viewing them as pests. Saraceno, who allows spiders to thrive in his own home, suggests that it is humans who are living in the spiders’ world rather than the other way round. As he puts it: “Spiders have been on the planet almost 280 million years and we humans only 300,000. With this letter on invertebrate rights, we say: ‘Hey look, spiders have the right also to come to the museum, spiders are around you’.”

Tomas Saraceno, the person, also breaks all the traditional perceptions of ‘artist’ and ‘scientist’. Trained both as an architect and a visual artist Saraceno’s works demonstrate a stunning intermeshing of art, physics, biology, astronomy and engineering. Saraceno is also an environmental activist who is constantly exploring new, sustainable ways to inhabit and sense the environment. In 2015, he achieved the world record for the first and longest certified fully-solar manned flight. In the quest for more sustainable ways of living he has worked closely with indigenous people as well as with renowned scientific and technological institutions.

Among all his other passions and accomplishments, Saraceno is an ardent ‘arachnophile’—an advocate for spiders and their ingenious airborne lifestyle, and spiders’ webs that inspire a lot of his work! As he often reminds us: “Somehow, when people talk about spiders, they forget that some spiders weave webs; [in fact,] they’re very dependent upon their multifunctional webs that provide shelter, protection, food and, when vibrated, a means of communication.”

The multi-functionality of the web, as well its unique structure, can be attributed to the incredible spider silk which it produces and uses not only to spin its web but which has multiple functions. Any individual spider can make up to seven different types of silk, but most generally make four to five kinds. This is produced in internal glands, moving from a soluble form to a hardened form, and then spun into fibre by the spinnerets on the spider’s abdomen.

The sticky silk prevents the prey from slipping off the web, and is useful to wrap and immobilize the prey once it is caught. The spider used the long strands or draglines as a safety line, to keep itself connected to the web; these are also used for parachuting or ballooning to help the young to disperse and find new areas as food sources; they also act as shelter for the spider. The chemical properties of the silk make it tough, elastic and waterproof. Each strand which is finer than the human hair is believed to be five times stronger by weight than steel of the same diameter, and thus has an incredible tensile strength. No wonder then, that Tomas Saraceno can use it for his installations!

Spiders are master engineers, gifted with amazing planning skills and a material that allows them to precisely design functional webs, which they create in a mind-boggling variety of patterns. Saraceno sees the web as vital for the life of a spider. “The web is a tool for a spider to sense what’s around them—it’s part of their body, almost. Some spiders are blind, or some spiders have eyes but their vision is very bad. They also don’t have ears—they can’t hear. They feel vibrations on their web to understand what’s going on around them. I wanted to build something that allowed a human to be inside the mind of a spider.”

It is this that drove his first major show in the United States called Particular Matter(s). This included a giant spider web installation that enabled humans to experience (in a dark room) the vibrations around them, as a spider would.

Saraceno was born in Argentina but currently lives and works in Berlin, and exhibits in different parts of the world. He is much more than an artist. He is a passionate social and environmental justice warrior. His mission, he feels, is simply to get humans to understand that they are not the top of a pyramid of power in what is called the Anthropocene era, but exist on a horizontal plane with all non-humans, to which they should be sensitized and from which they have plenty to learn. He advocates for what he prefers to call the Aerocene era in which interspecies-cooperation and clean air are required.

The exhibition that opens this week is yet another reminder of this message and its urgency. In India the first week of October is celebrated as Wildlife Week when the spotlight is usually on the more charismatic and larger mammals and birds. Tomas Saraceno’s mission to celebrate the less visible but vital members that make up the much larger proportion of ‘wildlife’ is a timely reminder that in the web of life, each and every strand is critical.

–Mamata