A recent piece by one of my favourite columnists bemoaned the fact that there is increasingly reduced use of physical dictionaries because of instant and easy access to online dictionaries.

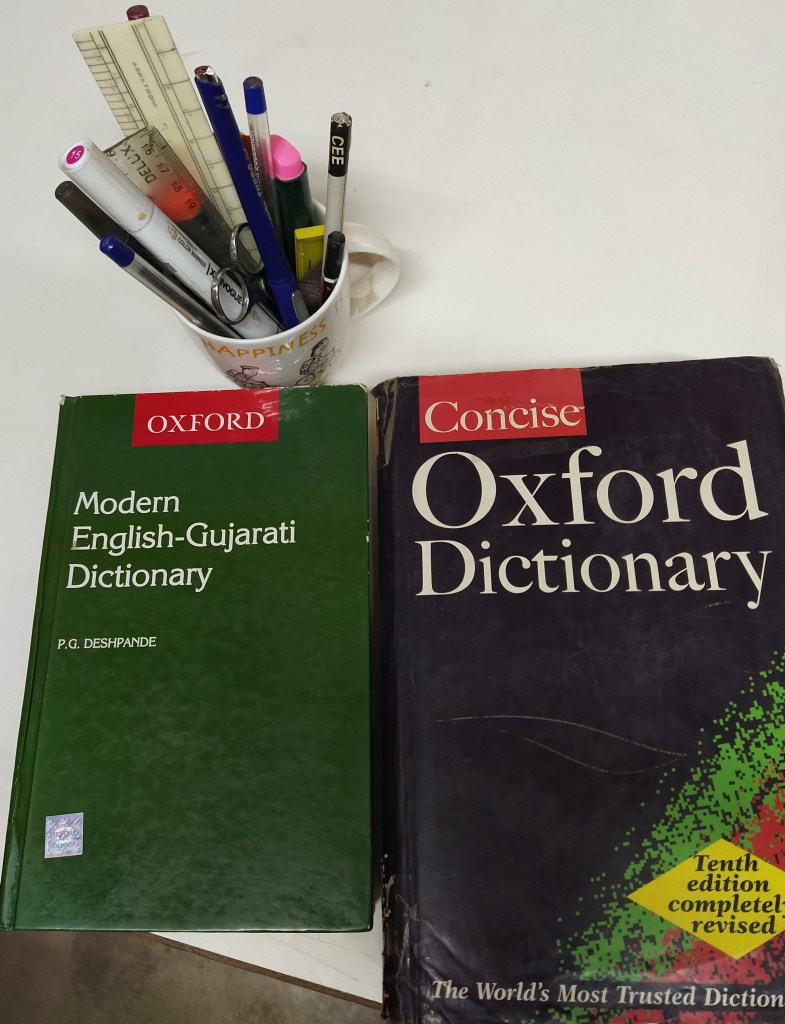

It made me feel a bit guilty as I have begun to succumb to the same short cut, but I still keep my trusty Concise Oxford Dictionary and my bilingual dictionary within hand’s reach on my table, and yes, I do look up words from these tomes. As my erstwhile colleagues may recall, the COD was a permanent fixture on my desk at work. This old friend continues to give me a sense of familiar comfort, as well as continuity in my work and play with words.

While COD is the friendly go-to dictionary, it is the Oxford English Dictionary or OED, which is widely regarded as the accepted authority on the English language. The OED today, is an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and pronunciation of 600,000 words, past and present, from across the English-speaking world. It contains not only not only present-day meanings, but also the history of individual words from over 1000 years of the English language, traced through 3 million quotations from a wide range of sources, from classic literature to cookery books.

What is equally fascinating is the history of the early development of the OED.

Until the 19th century, the English language did not have a complete dictionary. In 1857 the members of the Philological Society of London decided that it was time for a complete re-examination of the language, and embarked on an ambitious project to compile a comprehensive compendium of the English language.

The new dictionary was planned as a four-volume, 6,400-page work that would include all English language vocabulary from the Early Middle English period (1150 AD) onward, plus some earlier words if they had continued to be used into Middle English. It was estimated that the project would be finished in approximately ten years. However, no one realized the full extent of the work, or how long it would take to achieve the final result. After the first grand announcement, the project took a while to take off. And five years after it was launched the editors had only reached as far as the word ‘ant’.

Then in 1879 James Murray a little known school teacher and philologist was given the editorship of this challenging project. His first task was to advertise in all the leading newspapers of the day that the project was looking for ‘volunteers’ in the English-speaking world to send him quotations which would show how the meanings of words had changed over time.

This early experiment in crowdsourcing attracted many volunteers. The most prolific and systematic contributor was a man called Dr William Chester Minor. He regularly sent in meticulously detailed slips tracing the etymology of words, accompanied by relevant examples and quotations. The return address on his letters read simply: Broadmoor, Crowthorne, Berkshire.

For almost a decade, Murray assumed that his favourite volunteer was a reclusive doctor of literary tastes with a good deal of leisure. Then, by chance, Murray discovered that Minor was a murderer who had been committed to the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, which was less than 40 miles from Oxford where Murray was based. In 1891, ten years after they had started corresponding, Murray visited Broadmoor and met Minor. This was the start of a close friendship between the two men that continued for the next twenty years. And one that enriched the OED immeasurably.

Minor’s own story was tragic, as well as inspiring. Born in America, he qualified as a surgeon and joined the Union Army just before the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. After being released from the Army, Minor left for London in 1871 with his books and paints in the hopes of starting a new and more peaceful life. However the war experiences left deep scars on the sensitive and clever young man. He became delusional and paranoid. In one such moment he unintentionally shot a man and killed him.

Minor’s ‘insanity’ plea helped him to avoid going to prison. But he was incarcerated in the Broadmoor mental asylum in 1872. He was a well-behaved, quiet, scholarly inmate. With the approval of the asylum authorities, and using his US army pension he managed to accumulate and build a library of rare and antique books in his cell. It was this collection that provided the useful information about nearly 10,000 words, and examples of their usage, which he shared with Murray. The subsequent close friendship between the two which was marked by a common love for words and their history, scholarship, mutual respect and drive, was crucial in the compilation of the OED–the last word on words for over a century.

Murray acknowledged Minor’s invaluable contribution when in 1899 he said “we could easily illustrate the last four centuries from his quotations alone.” Murray also petitioned tirelessly for the release of his friend arguing that a mental asylum was no place for a man of his intellectual calibre. Sadly, Minor’s mental condition deteriorated. Finally he was released, and died in obscurity at his home in 1920.

The two men who gave half their lives to a project of unprecedented historical and cultural importance, did not live to see the publication of their magnum opus. It took roughly forty years for the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary to be completed.

So it was, the story that made the words, rather than the words that made the story!

–Mamata