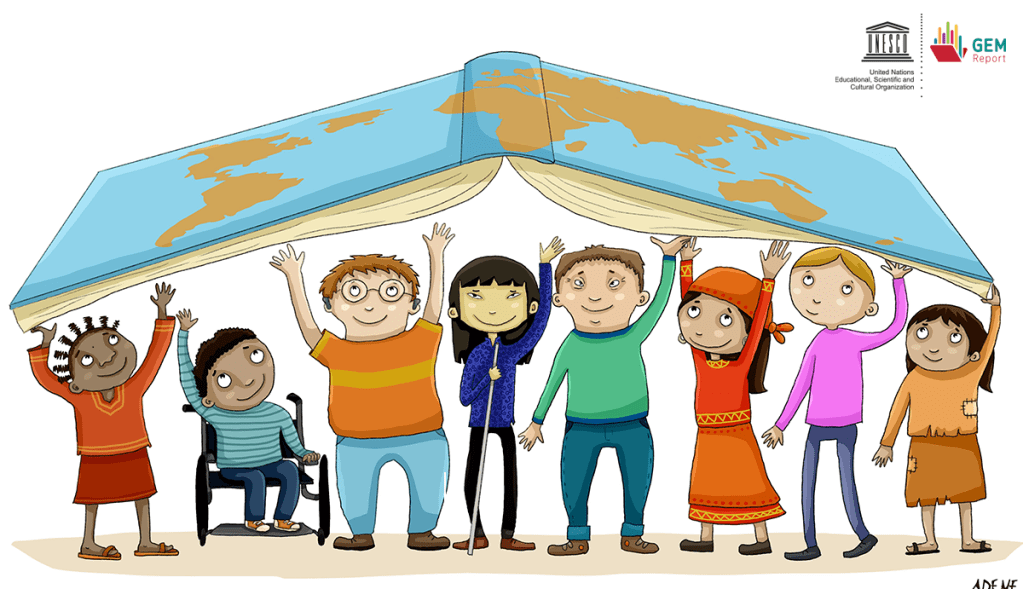

June 27 was declared as World Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) Day by the UN in 2017, to focus on the contribution of this sector to inclusive and sustainable development, both locally and globally. The importance of MSMEs is huge, but not fully registered in the mindsets of most people. Globally, they account for two-thirds of all jobs. In developing countries, 4 out of 5 new jobs in the formal sector were created by MSMEs. Many MSMEs in developing countries, especially the smallest, are often run by women.

There is no standard international definition of MSME. In India, as per changes brought in last year, the classification of units in the sectors is based on a composite of Investment in plant/machinery/ equipment as well as Annual Turnover.

| Classification | Micro | Small | Medium |

| Manufacturing and Service rendering Enterprises | Investment in Plant and Machinery or Equipment: Not over Rs.1 crore; and Annual Turnover not over Rs. 5 crore | Investment in Plant and Machinery or Equipment: Not over Rs.10 crore; and Annual Turnover not over Rs.50 crore | Investment in Plant and Machinery or Equipment: Not over Rs.50 crore; and Annual Turnover not over Rs. 250 crore |

For us, as for many other developing countries, this sector is critical in terms of contribution to employment and GDP. There are about 6 crore MSME units in India today, of which 99.4 per cent of are micro-enterprises, while 0.52 percent are medium, and 0.007 per cent, are medium enterprises. In other words, micro-enterprises dominate. MSMEs account for about 30% of GDP and about 48% of exports. They employ about 11 crore people. About 41% MSMEs are engaged in Manufacturing while 59% of them are in Service activities

The number of MSME units and the people employed have been growing for the last 4-5 years.

But the contribution to the GDP has been almost stagnant. This clearly speaks for the extremely low, and falling productivity of the sector. Studies estimate that Indian MSMEs have a productivity of at best 65% and at worst, 25% of such units in other countries.

This is compounded with the difficulties these units face in scaling up and accessing markets. And not to speak of the challenges of the external environment and regulatory environment challenges. The pandemic has devastated the sector. Not only have orders dried up, but even where there are orders, units have been hit with a reduction of workforce and huge challenges in procurement of raw materials.

In a scenario where jobs are getting scarcer and entrepreneurship is being seen as the answer, we obviously need to do many things at many levels. Speaking as someone engaged in the education and skilling sector, for me a major part of the solution has to do with Education and Training.

First and foremost, we need to get basic education right.

And then, respect for and practice of vocational skills, as well as concepts like quality consciousness and systematic approach to doing any task have to be inculcated right from primary levels. These are not mindsets which can be added on at a later stage. They are very fundamental to a person’s make up, and influence how he/she performs any task in later life.

Skill training has to be much more rigorous than it is today. A student in Germany for instance, would spend about 2 to 3.5 years learning a skill, spending half the time in vocational school and half the time in a real factory, being systematically trained. We are ready to certify youth who go through a 3-month programme as skilled! And even pass-outs from ITI institutions or Polytechnics who spend a longer time, still have zero exposure to any real life workplace situation, and at best spend some time on old and outmoded machines. Not a recipe for productivity!

Third, MSME entrepreneurs need management education. Whether it is managing finances or people, production or marketing, each small entrepreneur seems to be making mistakes, discovering first principles, and reinventing the wheel. Surely not conducive to productivity. There are such initiatives, but they seldom reach the grassroots and the audience who really need these inputs.*

MSMEs have a huge role to play in inclusive development. They have the potential to impact the lives of the poorest, the most vulnerable through creation of local businesses. We need to act now!

–Meena

PS: Those interested in MSMEs and Skilling should watch a webinar by National Skills Network on the subject.

- * I am currently involved in a very interesting initiative of developing an ‘MBA’ programme for rural women entrepreneurs who are Std 8 pass and above. An initiative of Access Livelihoods supported by GIZ.