Last week I wrote about Children’s Day. Earlier this month two other important international days passed almost unnoticed. 13 November which is designated as World Kindness Day, and November 16 which is marked as International Day for Tolerance and Peace.

For its fiftieth anniversary on 16 November 1995, UNESCO’s Member States adopted a Declaration of Principles on Tolerance. Among other things, the Declaration affirms that tolerance is respect and appreciation of the rich variety of our world’s cultures, our forms of expression and ways of being human. While this is a universal ideal and aspiration, it is at the level of the individual that the foundation of tolerance and respect is laid.

And this is what the World Kindness Day seeks to do–reinforce the understanding that compassion for others is what binds us all together. It is this that has the power to bridge the gap between people, communities and nations. This global day promotes the importance of being kind to each other, to oneself, and to the world.

The idea of this day was promoted by an international non-profit organisation called the World Kindness Movement which works to inspire individuals towards greater kindness to create a kinder world; and their guiding tenet: The world is full of kind people. If you can’t find one, be one.

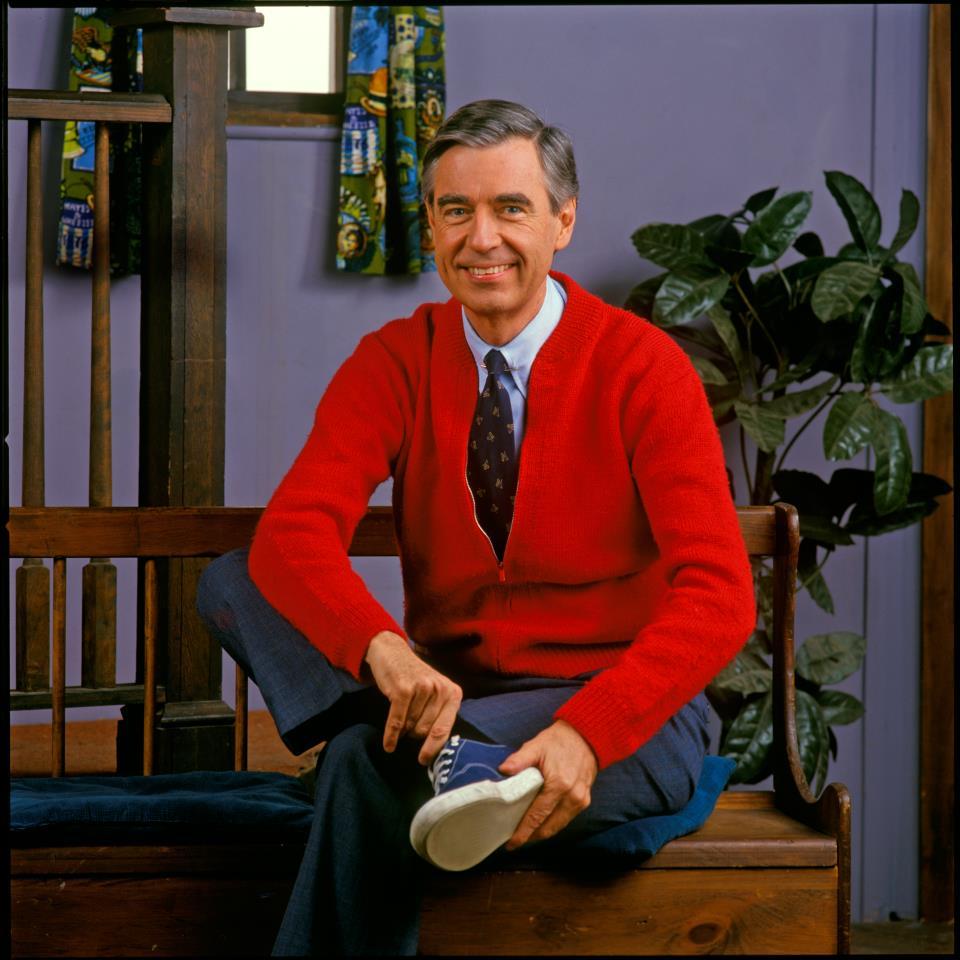

Nothing, and no one, exemplifies the spirit and practice of all the three days better than the beloved Mr Rogers whose TV show celebrated kindness, and helped millions of children to develop empathy.

I came upon the inspiring story of Mr Rogers via Tom Hanks when I saw the movie A Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood. After seeing Tom Hank’s version I wanted to know about the real Mr Rogers!

Fred McFeely Rogers grew up in America in the 1930s as a shy, somewhat awkward, and sometimes bullied child. After getting his first degree in music, he returned home for the vacation before he prepared to enter the seminary and study to become a priest. It was then that he saw television for the first time at his parent’s home. He was appalled to see the kind of programmes where as he said ‘people were throwing pies in each other’s faces.’ While he found this disgusting, he also saw the enormous potential that TV had for connection and enrichment. That eureka moment changed his life—and the lives of millions of Americans.

Fred Rogers went on to create a TV show called Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, which first aired on 19 February 1968 and continued for over 30 years. The last episode of the 31 seasons was aired on 31 August 2001. Fred Rogers was the host of all 895 episodes, the composer of its more than 200 songs, and its puppeteer.

The set of simple hand puppets featuring 14 characters from his first show continued to be with the friendly Mr Rogers, clad in his trademark red cardigan and sneakers, for over 40 years. The puppets who inhabit the Neighbourhood of Make Believe, portray real-life feelings as they live and learn with the help of their neighbourhood human friends who represent a wide variety of interests and talents. The puppets and the humans live together, care about and learn from each other. As they often reminded viewers “We all have different gifts, so we all have different ways of saying to the world who we are. It’s our job to encourage each other to discover that uniqueness and to provide ways of developing its expression.”

Mr Rogers was far from preachy. He did not shy away from difficult topics like bullying, divorce, and death; he talked honestly and openly about subjects that adults are hesitant to discuss with children, but that children wonder and worry about silently. He reassured children and adults that it was ok if there were some things that they could not understand. He addressed children’s fears and insecurities, and instilled a sense of faith and trust. “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping”.

Although Fred Rogers later acquired graduate degrees in child development as well as divinity, he always consulted with his close associate and child psychologist Dr Margaret Mcfarland, to ensure that his scripts would authentically reflect the real concerns and feelings of children.

His show also offered children the tools to be lifelong learners—a sense of wonder, a curiosity about the world around us, the willingness to ask questions. “Did you know, when you wonder you are learning?”

The concept of neighbour and neighbourhood in the leitmotif of Mr Rogers’ life and work. “Neighbours are people who live close to each other. Neighbours look at each other, they talk to each other; they listen to each other. That’s how they get to know each other.” In his neighbourhood everyone was welcomed and valued, and the characters taught how to appreciate and respect others.

Mr Rogers’ ‘neighbourhood’ in a sense becomes the symbol of community; it extends beyond a residential address to embrace the city, the country, the continent, and ultimately the planet that we all inhabit. It metaphorically embraces the universe. And it reminds us of the dire need for, and the gentle power of sharing and compassion. “All of us, at some time or other, need help. Whether we’re giving or receiving help, each one of us has something valuable to bring to this world. That’s one of the things that connects us as neighbours—in our own way, each one of us is a giver and a receiver.”

Today teaching and learning respect, tolerance, sharing, acceptance of differences, and celebration of diversity are highlighted in “values education” curricula. This is the kind of education proposed by UNESCO in its declaration of four pillars of education, i.e. learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together and learning to be.

Over 50 years ago Fred Rogers planted the seeds of basic human values in millions of children, who must themselves have grandchildren now! And for all this he offered only one mantra: “There are three ways to ultimate success: The first way is to be kind. The second way is to be kind. The third way is to be kind.”

–Mamata

The school showed amazing results. Soon the children exhibited great interest in working with puzzles, learning to prepare meals and clean their environment, were calm, orderly, self-regulating, and engaging in hands-on learning experiences—essentially teaching themselves.

The school showed amazing results. Soon the children exhibited great interest in working with puzzles, learning to prepare meals and clean their environment, were calm, orderly, self-regulating, and engaging in hands-on learning experiences—essentially teaching themselves. But I think this puts a greater and different responsibility on the Ministry of Women and Child Development—viz, the responsibility of educational inputs in the home environment for children below the age of 3. Ages 0-3 is when a baby’s brain grows to 80% of its adult size and is twice as active as adults. Research in developed countries has shown that at age 2, toddlers from low-income families are already 6 months behind in their language processing skills. Without greater investment in the first 3 years, many children will miss the opportunity to reach their full potential. And inputs and influences at this age come mainly from the home environment.

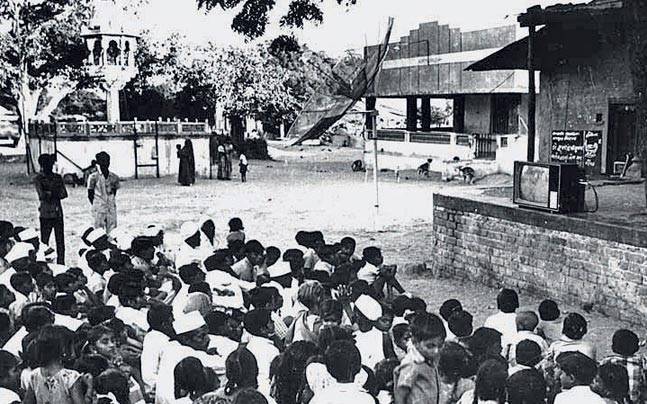

But I think this puts a greater and different responsibility on the Ministry of Women and Child Development—viz, the responsibility of educational inputs in the home environment for children below the age of 3. Ages 0-3 is when a baby’s brain grows to 80% of its adult size and is twice as active as adults. Research in developed countries has shown that at age 2, toddlers from low-income families are already 6 months behind in their language processing skills. Without greater investment in the first 3 years, many children will miss the opportunity to reach their full potential. And inputs and influences at this age come mainly from the home environment. Today, All India Radio is the largest radio network in the world, and one of the largest broadcasters i in terms of the number of languages broadcast (23 languages and 179 dialects!), and the range of audiences it serves. This is done through 420 stations located across the country, reaching nearly 92% of the country’s area and 99.19% of the population. AIR also operates close to 25 FM stations.

Today, All India Radio is the largest radio network in the world, and one of the largest broadcasters i in terms of the number of languages broadcast (23 languages and 179 dialects!), and the range of audiences it serves. This is done through 420 stations located across the country, reaching nearly 92% of the country’s area and 99.19% of the population. AIR also operates close to 25 FM stations. The programs were broadcast for a few hours a day, and hundreds of

The programs were broadcast for a few hours a day, and hundreds of