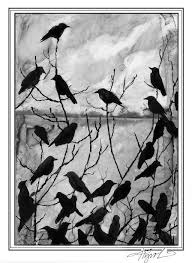

A few days ago our champa tree was the venue for an impromptu gathering of crows. They descended literally out of the blue and within flapping seconds, settled onto the branches and commenced a raucous chorus. What a “cawcaphony” I said to myself and peeped out to investigate the cause of the assembly. It turned out that there was a dead crow not far from the tree, and the incident was being marked with a suitable mourning from its clan. Quite spontaneously, I remembered that the collective noun for a group of crows is called a ‘murder’ of crows. Well here I was witness to a murder of crows in action!

Why this descriptor? The term is believed to have originated in England in the 15th century, and was linked to old folk tales and superstitions. In the Middle Ages, collective nouns were often given to animals based not only on their behaviour but also on superstitions or prevalent attitudes towards them.

One among these was the belief that crows will come together to decide the fate of another crow (a court of crows?). Another belief was that the appearance of crows was an omen of death. Yet another, based on the fact that crows are scavengers and were thought to circle over areas where animals and people were expected to die. A more scientific reason for his may be that crows are opportunistic feeders and will eat everything–carrion, small animals, insects, or crops, and thus find their way to wherever these may be available.

In fact, crows, though often considered to be pests, and generally irritating, are a highly intelligent and social species. They have the ability to create and use tools, they have been known to solve multi-step puzzles. They are extremely social birds that flock together and also have an ability to learn from each other.

Another interesting aspect of crow communities is that they have been shown to recognize their dead and hold “funerals” for dead individuals, something that has only been observed in a few other species including elephants, dolphins and some primates. This could be an unsettling scene for observers, (probably what I witnessed) but scientists believe this is a way by which they communicate to their fellow crows about potential threats to be avoided.

Besides ‘funerals’ why do crows flock together? For many reasons. Crow are smart and adaptable, and gathering in large groups is often both a solution to a problem and a social benefit. Communal foraging strengthens social bonds and hierarchies within the crow community as well as efficiency. Communal roosting provides safety from predators and establishes social bonds, social learning and information.

The ‘cawcaphony’ also has its reasons. Loud and distinctive cawing is used to convey messages about food locations, to call others for support in defending their territory, or to alert the flock of approaching predators. There are specific caws for different types of danger. As well as caws, crows have softer calls which are used within family groups.

Yes crows are a part of our lives, generally around, but not really headline grabbers. Until recently, when crows have been in the news. And this time the news is about a literal “murder of crows”. The target of this planned execution is the Indian house crow Corvus splendens, whose population is being systematically eliminated in Kenya.

The story of the crow in Kenya goes back to the 1880s when it is believed that the first few pairs of Corvus splendens arrived on the island of Zanzibar by ship. One story goes that a breeding pair was presented to the Sultan of Zanzibar as a gift from an Indian dignitary. Another account believes that the scavenging crows were brought to the island in a bid to clean up the garbage. The introduced species soon gained a foothold not only on the island, but also spread to nearby mainland countries like Tanzania and Kenya. Showcasing all their traits of intelligence, adaptability and resourcefulness, the crow population grew rapidly and began to not just scavenge but also raid crops and poultry farms, as well as food sources in urban areas. By 1917, House crows were officially declared as ‘pests’ by the local authorities.

The House crow reached Kenya in 1947, and since then its numbers have exploded. The growing human population, both local and tourists (tourism is the mainstay of Kenyan economy) has led to growing waste sites with mounds of garbage. The municipal authorities have not been able to efficiently manage the waste. This has led to a huge proliferation of crows who not only feed on the garbage but have also learned to mob eating places and swoop up food from diners’ plates.

Besides the pestering of humans, conservationists are concerned that the overwhelming numbers of crows are driving out many smaller indigenous species of birds, impacting biodiversity. With decline in indigenous bird species, pests and insects begin to proliferate, impacting local flora as well as crop plants. This is one more case of how invasive species can impact local ecosystems.

The Kenyan government undertook a programme to control the invasive bird species twenty years ago. While this helped reduce the crow population for some time, the resilient species bounced back with an exponential rise in numbers. In the past there this menace has been addressed with the baiting of food with Starlicide, a slow-acting poison to tackle the crow menace. This time the Kenyan government is planning to use all methods, including this, to eliminate a million crows by the end of the year. A sad, but perhaps unavoidable, murder of crows.

And just last week was the news that the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to kill half a million Barred owls across the states of California, Washington and Oregon over the next ten years. This is because the population of Barred owls is crowding out its less aggressive relative the Northern spotted owl which is an endangered species. This news has sparked of several debates. While this is not a case of an invasive species, it is a case of one species becoming dominant, to the detriment of other species. There is also the moral issue of killing one species to protect another. Perhaps it will take a ‘parliament of owls’ to resolve the case!

See also:

The Camel in the Tent: Invasive Animal Species

A Parliament of Owls

–Mamata