This week Meena wrote about World Book Day on 23 April. Not exactly coincidentally, this day is also marked as English Language Day. English Language Day is the result of a 2010 initiative by the UN’s Department of Global Communications, establishing language days for each of the Organization’s six official languages (English, French, Spanish, Chinese, Arabic, and Russian).The purpose of the UN’s language days is to celebrate multilingualism and cultural diversity, and to promote equal use of all six official languages throughout the Organization. English Language Day celebrates the English language and promotes its history, culture and achievements.

Books certainly come in all the languages of the world, but the very fact that we are, at this moment, reading and writing in English, is a testimony to the fact that English is indeed one of the languages that unites word lovers across the world. English is one of the languages of international communication; it enables people from different countries and cultures to communicate with each other in a common language, even if it is not their first language.

April 23, as English Language Day, celebrates the life and works of William Shakespeare, who not only died on this day, but is also believed to have been born on the same date in 1564. The day is a tribute to the enormous contribution that Shakespeare made to the English language.

Shakespeare’s prodigious output of sonnets and plays was remarkable as a body of creative work. These literary works were expressed in thousands of words, many of which (1700 it is believed), he created himself! When he embarked on his literary marathon, there were no dictionaries that Shakespeare could dip into. The first such reference to meanings of words in English was A Table Alphabeticall that was published in 1604. Texts on grammar appeared only in the 1700s. Thus Shakespeare did not have ready resources which could be used to populate his vocabulary.

Scholars believe that Shakespeare’s vocabulary owed to a combination of sources. It is likely that he lent an alert ear to the commonly spoken language of the time, and drew words from there which were written into his plays and verses. Thus he can certainly be credited with the ‘first recorded uses’ of numerous words. But he was equally a master of wordplay. He coined new words himself, often by combining words (eye and ball to make eyeball) changing nouns into verbs (from ‘elbow’ to ‘elbow someone out’), adding prefixes and suffixes into preexisting words. He anglicised foreign words, such as creating ‘bandit’ from the Italian ‘banditto’, and the word ‘zanni’ which referred to characters in sixteenth-century Italian comedies who mimicked the antics of clowns and other performers, and used it as a noun–zany.

These introduced words were soon adopted into the English language, enriching it considerably.

I must admit that in my younger days, I did not take as easily to Shakespeare in the original as may have been done by the more “literary types” of my generation. Whatever Shakespeare we were exposed to was in the form of the ‘abridged and simplified’ versions that made their way into English language textbooks year after year. Yes, we knew that “a rose by any other name”, and “all the world’s a stage” and “all’s well that ends well” was quintessentially Shakespeare, but I for one did not know that so many words that we use today, imagining them to be ‘contemporary’ language were coined and couched in William’s prose and poetry!

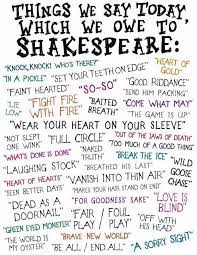

Here are some very ‘modern’ terms that first appeared in Shakespeare’s writing.

Addiction, assassination, auspicious, baseless, barefaced, bedroom, champion, cold-blooded, critic, elbow, fashionable, generous, gloomy, hint, hostile, lackluster, lonely, majestic, manager, obscene, overblown, puking, pious, radiance, reliance, skim milk, submerge, swagger, watchdog!

Here are some that have not travelled intact through the centuries. Today some of these are “Greek to us” (incidentally it is Shakespeare who first coined this phrase!).

Mobbled: With face muffled up, veiled.

Foison: Abundance, plenty, profusion

Ganesome: Sportive, merry, playful

Noddle: The back of the head

Fleshment: The excitement associated with a successful beginning

Gratulate: Greet, welcome, salute

Kicky-wicky: Girlfriend, wife

Bawcock: Fine fellow, good chap

Buzzer: Rumour-monger, gossiper

Gallimaufry: Complete mixture, medley, hotchpotch

Garboil: Trouble, disturbance, commotion

Miching: Sulking, lurking, sneaking

For Shakespeare “all the world was a stage” and he also coined a number of colloquial phrases that added drama to the dialogues of his many characters, from Romeo and Juliet to Othello, from the Merchant of Venice to Hamlet and Macbeth. These “as good luck would have it” continue to enrich our speech even today.

All that glisters is not gold

A sorry sight

Bated breath

Break the ice

Cold comfort

Come what may

Dead as a doornail

Devil incarnate

Eaten me out of house and home

Fair play

Green-eyed monster

Laughing stock

Naked truth

In a pickle

Seen better days

Set your teeth on edge

The world is my oyster

Too much of a good thing

Vanish into thin air

Wild-goose chase

What’s done is done

And, it is not Sherlock Holmes but Shakespeare who first said “the game is afoot!”

Shakespeare may be “as dead as a doornail” but he remains the most quoted writer in English of all time. How zany is that!

Well, words maketh a book, and Shakespeare maketh words!

–Mamata