How often we randomly pick up a feather as we walk along. And wonder which bird it could belong to.

A feather library is where we can turn to for help in such a situation. These are digital or physical collections of bird feathers, used for research and education. They are an invaluable resource for understanding bird species, identifying feathers, and gathering data on bird health and natural history. These libraries are important tools for the study and conservation of bird species, offering insights into bird morphology and helping in the identification of feathers found in the wild.

There are not too many across the world. Some of the established ones include:

1. The Feather Atlas created by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is a comprehensive image database of North American birds and covers about 438 species. It can be browsed by bird order, family, or species. It has an open identification tool in which one can fill in details about feather patterns, colors, size, and position, which can help you identify the bird your feather belongs to.

2.Featherbase (Germany) has been created by a working group of German feather-scientists and other collectors worldwide who have come together and contributed their personal collections. It holds close to 8000 specimens from over 1,000 bird species, with a focus on European and African birds. The collection includes high-resolution images and detailed anatomical information, and has supporeted studies in forensics, conservation, and biodiversity monitoring. It is rigorously classified and offers options of various languages so that birders from across the world can use it.

3. Found Feathers (iNaturalist Project) is a citizen science initiative where users contribute observations of feathers they find. The project encourages the collection of feather length and placement data, enhancing the database’s utility for researchers and birders. There are over 2,00,000 observations from across the world.

Special among these is India’s Feather Library. This pioneering initiative is the first of its kind in India and the world, dedicated to documenting, identifying, and studying the flight feathers of Indian birds. It is the passion project of architect Esha Munshi, a dedicated bird watcher who has seen over 1500 bird species across the world, and veterinarian Sherwin Everett who works in a bird hospital in Ahmedabad. They have created the library with the aim of having all feather-related data under one roof, fostering collaboration and advancing the collective understanding of Indian birds. In the short span of time since inception on Nov 15, 2021, 135 species have been documented.

The process is rigorous. They collect feather specimens from dead birds at rescue centres to establish a primary database of bird species. They then make detailed notes on the flight feathers, taking into account the number of Primaries, Secondaries, Tertials (Wing Feathers), and Rectrices (Tail Feathers), along with basic details such as overall length, bill length and width, leg lengths, etc. Then they stretch out one wing and fan the tail in both dorsal and ventral views to document the exact number of feathers, unique characteristics, colour, pattern, and size etc. The physical collection is housed at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bangalore.

The database is open to all and provides easy access.

Kudos to the dedication and passion of people like Esha and Sherwin who through their efforts help support avian research, conservation efforts, and educational outreach. And make a better world.

Happy Environment Day!

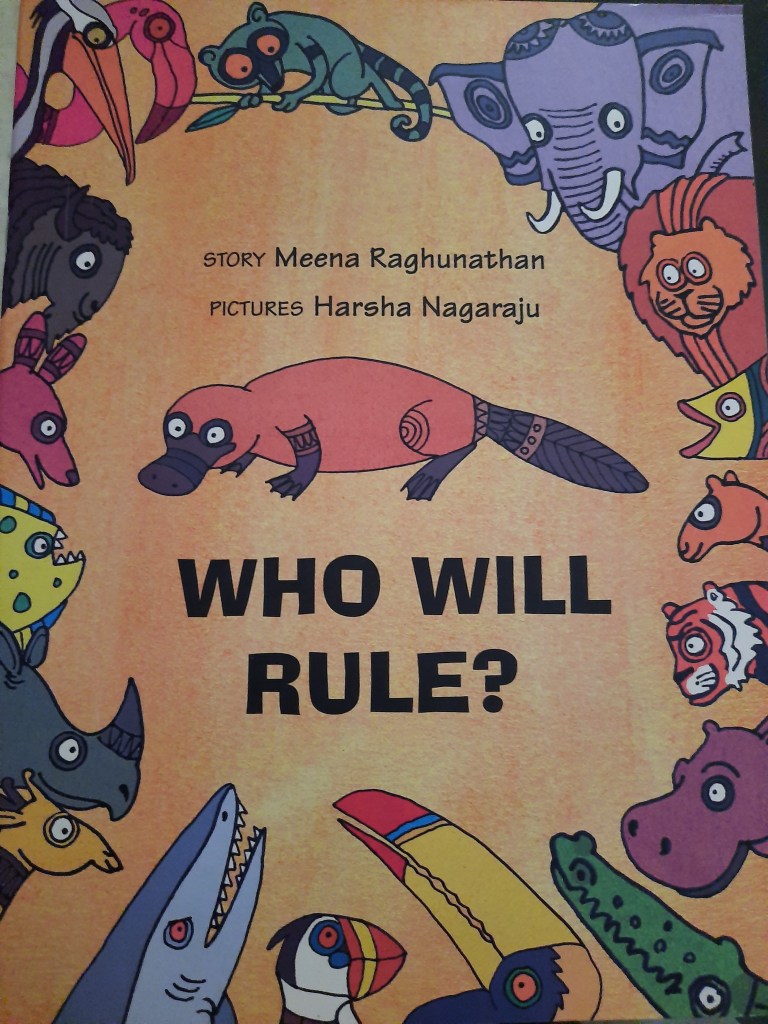

–Meena

n I was growing up in Delhi, house sparrows were very much a part of our lives. They were everywhere, and by the dozens. In fact, most children of those times got their first nature lessons by watching sparrows—the sex differentiation, how they built their nests, the eggs hatching and the parents feeding the young, their mud-bathing etc.

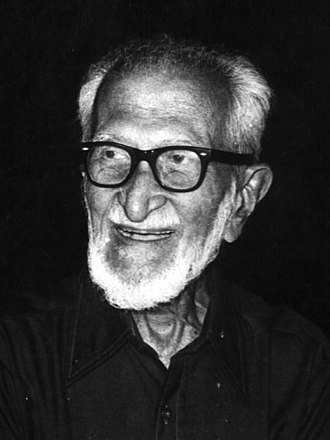

n I was growing up in Delhi, house sparrows were very much a part of our lives. They were everywhere, and by the dozens. In fact, most children of those times got their first nature lessons by watching sparrows—the sex differentiation, how they built their nests, the eggs hatching and the parents feeding the young, their mud-bathing etc. Salim Ali’s birthday falls on 12 Nov. He was born in 1896 and passed away in 1987. He may be credited with single-handedly bringing ornithology to India. And this interest in ornithology, as it spread, led to interest in wildlife and biodiversity; in environmental issues; in conservation; and in sustainable development.

Salim Ali’s birthday falls on 12 Nov. He was born in 1896 and passed away in 1987. He may be credited with single-handedly bringing ornithology to India. And this interest in ornithology, as it spread, led to interest in wildlife and biodiversity; in environmental issues; in conservation; and in sustainable development.