The last couple of weeks we have been hearing a new addition to the usual morning symphony of bird calls in our garden. This new sound was different—a somewhat harsh and raucous intermittent call. The other birds fall silent while this fills the air. As we looked for the source of sound, at first we could not see anything except the familiar babblers and doves and crows going about their morning business, until a rustling among the drying leaves of the tall old palm tree caused us to look closer. Suddenly we saw a hitherto unknown bird emerge and perch on the branch. Another swoop brought its partner flying from beyond to perch next to it. The first thing that struck us was the striking colouring and long tail that set these birds apart from the more staid and dull-hued birds that usually frequented the tree.

The tree-pies were in the neighbourhood! Last year they had caused a similar excitement when we had spotted them one day, but sadly that was only a one-time sighting, and we did not see them again. This time it seemed as if they were seriously prospecting the tree as a suitable site for potentially settling in to nest and breed.

The Rufous treepie (Dendrocitta vagabunda) belongs to the Corvidae family, to which also belongs the common crow. The bird is endemic to the Indian subcontinent, and it is found in open forests, woodlands, groves and gardens in cities and villages. This species is not found elsewhere.

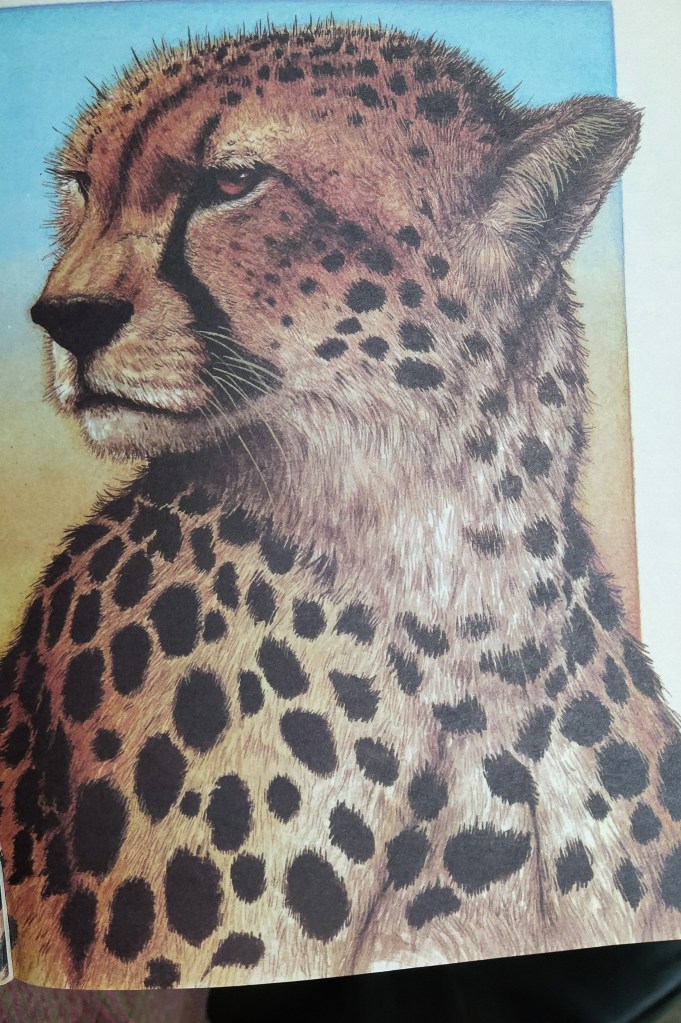

The body of the bird is the size of a myna, but it is elongated with a long tail which distinguishes it. The body is rust orange, with an ashy-black head and breast. The tail feathers are black interspersed with light grey, and the wing feathers are black with a white-grey band down the outside. The beak, legs and feet are black; the eyes are deep red with black pupils. The beak is slightly hooked at the tip. With such striking colouring, the tree pie makes quite a contrast to its relative, the common crow, with its monochromatic colouring.

What this bird does share with its Corvid family kin is the attraction to shiny objects. Tree pies look for and steal shiny objects such as coins and small jewellery, and stash these in their nest. Possibly a male ploy to attract the females! No wonder then that one of the local Indian names for this bird is taka chor, literally ‘coin stealer’. The bird is also called kotri, derived from one of its calls which sounds like a screeching ‘ko-tree’.

The tree pie indeed has quite a repertoire of calls—from the loud, harsh and guttural to some which are sweet and melodious like ko-tree or bob-o-link. Thus it is confusing when one looks for the source of the squawking call, only to find a melodious tune emanating from the same place. It makes one wonder if it is one bird or several different ones calling.

The tree pie is an arboreal bird, rarely seen on the ground. It is an agile climber and hops agilely from branch to branch, or flies from tree to tree with a swift noisy flapping followed by a short glide on out stretched wings.

The rufous tree pie is an omnivorous and opportunistic feeder. Its diet includes fruits, seeds, small lizards, insects, as well as the eggs of other birds, and even small birds and rodents. In the forest tree pies often join mixed hunting groups of birds like drongos and woodpeckers; they collectively disturb insects in tree canopies and feast on them.

Tree pies make their nests concealed in the foliage of middle-sized trees. The nest resembles that of its cousin the crow, made of thorny twigs, but it is deeper and well-lined with rootlets. It is here that 4-5 eggs are laid, and when they hatch both male and female share the parental duties.

A fortnight has passed since we heard the first harsh call of the tree pies. Since then we have been able to also enjoy the rest of their repertoire, in something like sound-surround. The soft melodious chirping coming from the foliage of the karanj tree, the bob-o-links that punctuate from the neem tree, and the kotri call from the top of the straggly palm. If we look hard enough we can also spot the tip of the long tail peeping out from the leaves, and occasionally are treated to a glimpse of its sweeping graceful flight from one perch to the other. It looks like the tree pies are here to stay this year.

–Mamata