One has heard of herbal teas, herbal treatments and herbal facials, but this was the first time that I heard about a curious herbal! Of course my curiosity was piqued! I discovered that while today the word ‘herbal’ is generally used as an adjective, it is also a noun that refers to ‘a book of plants, describing their appearance, their properties and how they may be used for preparing ointments and medicines’. And thus this was the title of such a book first published in England in 1737. The book consisted of five hundred illustrations drawn, engraved and hand-coloured by Elizabeth Blackwell. This was indeed a voluminous ‘herbal’. Why the added adjective ‘Curious’? This refers to an old use of the word to mean ‘accurate and precise’.

The story of Elizabeth Blackwell herself, and how she came to create this book is itself curious and unusual.

Elizabeth Blackwell was born in 1707 in Aberdeen in Scotland. Her father Leonard Simpson was a painter and his daughter inherited his artistic talent. From a young age she loved drawing and painting, and was constantly observing and sketching the natural world around her.

Elizabeth married Alexander Blackwell a doctor and an accountant. They had to move to London when it was discovered that her husband was practicing medicine illegally. But even there Alexander’s unlawful activities resulted in heavy debts that caused him to be imprisoned. Elizabeth was left alone to fend for herself and her child. In an age when women were not part of the work force Elizabeth drew upon her skill as a botanical artist for survival and sustenance.

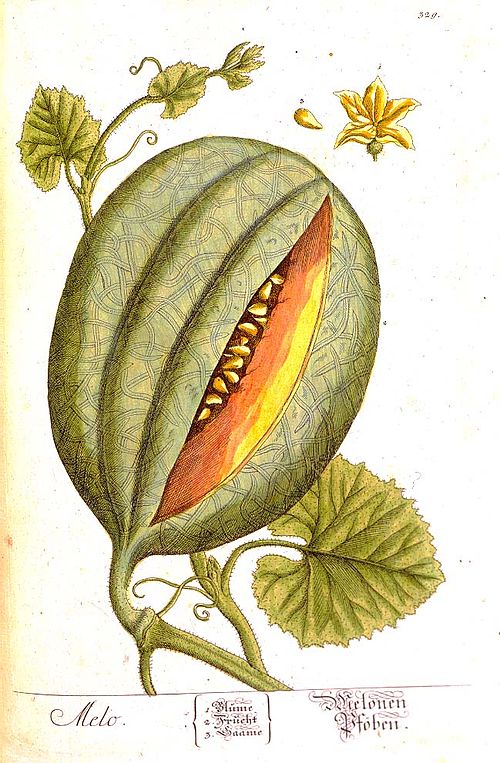

In the early eighteenth century, plants were an essential resource for healthcare. Choosing the right plant to treat an ailment was an increasingly precise science, and mistaking one plant for another could have severe consequences. Elizabeth thought of creating an ‘herbal’, an illustrated reference book to help doctors and apothecaries to develop an “exact knowledge” of medicinal plants, their uses and effects in medicine. Before embarking on the project she consulted various botanists and herbalists who advised her that pictures alone would not suffice, these needed to be accompanied by descriptive and explanatory notes. Elizabeth, being trained neither in botany nor in medicine, realized that she would need these inputs from experts.

But in order to do all this she first needed access to the plants. The Apothecaries Garden (later called the Chelsea Physic Garden) had a vast collection of medicinal plants from many parts of the world. The garden’s director Isaac Rand gave Elizabeth access to the garden. Elizabeth moved with her daughter, to some rooms close to the garden, and threw herself into making botanical drawing from the actual specimens. She began to document the garden’s many indigenous plants, as well as specimens arriving from across the British Empire. She set about not only making highly detailed, analytical drawings of plants from different perspectives and in different stages of growth within the same picture. In addition to their physical characteristics, she also included information about where and when they could be found; their names in a variety of languages; and their curative properties

Her paintings of the plants were precise, and with an artist’s eye, she described the colour and texture of plants in minute detail. She would take each set of completed drawings to her husband in prison and he drafted descriptions for each one. She also managed to get for each plant, along with its English common name, its name in Latin, Greek, Italian, Spanish, Dutch and German. This was in the days well before the Linnaean system of binomial nomenclature provided a system of universal identification. In fact Linnaeus was born in the same year as Elizabeth.

She also became known to prominent doctors and intellectuals who also helped with the supporting text. When a number of the drawings were ready, a team of nine eminent physicians, apothecaries, and a surgeon examined them, and endorsed their authenticity

Elizabeth worked non-stop. She drew, engraved, and hand-coloured each image, managing the work that would normally require several different craftsmen. She prepared four plates every week in instalments, (125 weeks) until she had produced 500 images with bullet points for the medicinal uses for each plant. Elizabeth Blackwell’s illustrations deeply impressed many English physicians, botanists, and apothecaries in mid-18th century London.

Originally published in weekly parts, the first collected volume of A Curious Herbal appeared in 1737. A Curious Herbal received an official commendation from the Royal College of Physicians. Capitalising on this support, E. Blackwell advertised her publication through word of mouth and journal advertisements. It met with moderate success. A second edition was printed 20 years later in a revised and enlarged format.

Through her industry and perseverance Elizabeth was able to pay off her husband’s debts and secure his release from prison. However her personal life continued to be challenging. Her husband Alexander got himself into fresh financial and political difficulties, and was forced to move to Sweden where he was eventually executed for conspiracy. Elizabeth never saw her husband after he left England for Sweden. But she continued to be loyal to him, even sending him a share of the royalties from her book.

She produced no more botanical works. But A Curious Herbal remains a landmark book in the field of medical botany and botanical illustration. In eighteenth century England, with no standing within London’s scientific and medical institutions, Elizabeth Blackwell managed to produce a work that became a standard reference for apothecaries. A Curious Herbal is a monument to Elizabeth Blackwell’s skill not only as a botanist and artist, but also a testament to her remarkable strength of purpose, and entrepreneurship in a male-dominated age when women were only seen as wives and homemakers.