On 10 April 1633, the window display of the shop in London attracted huge crowds. It displayed a hitherto unknown, and unnamed item. The displayer Thomas Johnson, a herbalist, botanist and merchant described it thus: The fruit which I received was not ripe, but greene. This stalke with the fruit thereon I hanged up in my shop, were it became ripe about the beginning of May, and lasted until June. Each of them (the fruit) was the bignesse of a large beane some five inches long and an inch and a half in breadth. The stalk is short and like one’s little finger. They hang with their heads down, but if you turn them up, they look like a boat. The husk is easily removed. The pulp is white, soft and tender and ate somewhat like a musk melon.

What was this fruit that he so described? Hard to believe, but this was the banana! How, and from where a bunch of this mysterious fruit reached the shop remains a mystery in itself, but it is believed that most people in England had not seen a banana even by the end of the 19th century when regular imports started from the Canary Islands.

And yet, it is believed that bananas were among the oldest cultivated fruit. They probably originated in the jungles of Malaysia, Indonesia or the Philippines and some parts of India where they grew in the wild. Modern edible varieties of the banana have evolved from the two species–Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana and their natural hybrids, originally found in the rain forests of S.E. Asia.

During the seventh century AD their cultivation spread to Egypt and Africa. The fruit may have got its name from the Africans, as the word is derived from ‘banan’ the Arab word for ‘finger’. A cluster of bananas is called a ‘hand’.

Bananas were first introduced to the Western world when Alexander the Great discovered them during his conquest of India in 327 B.C. The fruit spread through Africa and was eventually carried to the New World by explorers and missionaries. Bananas started to be traded internationally by the end of the fourteenth century.

However it was not until the late mid-1800s that bananas became widespread on the North American continent. The first enterprise to import bananas into the US was the Boston Fruit Company.

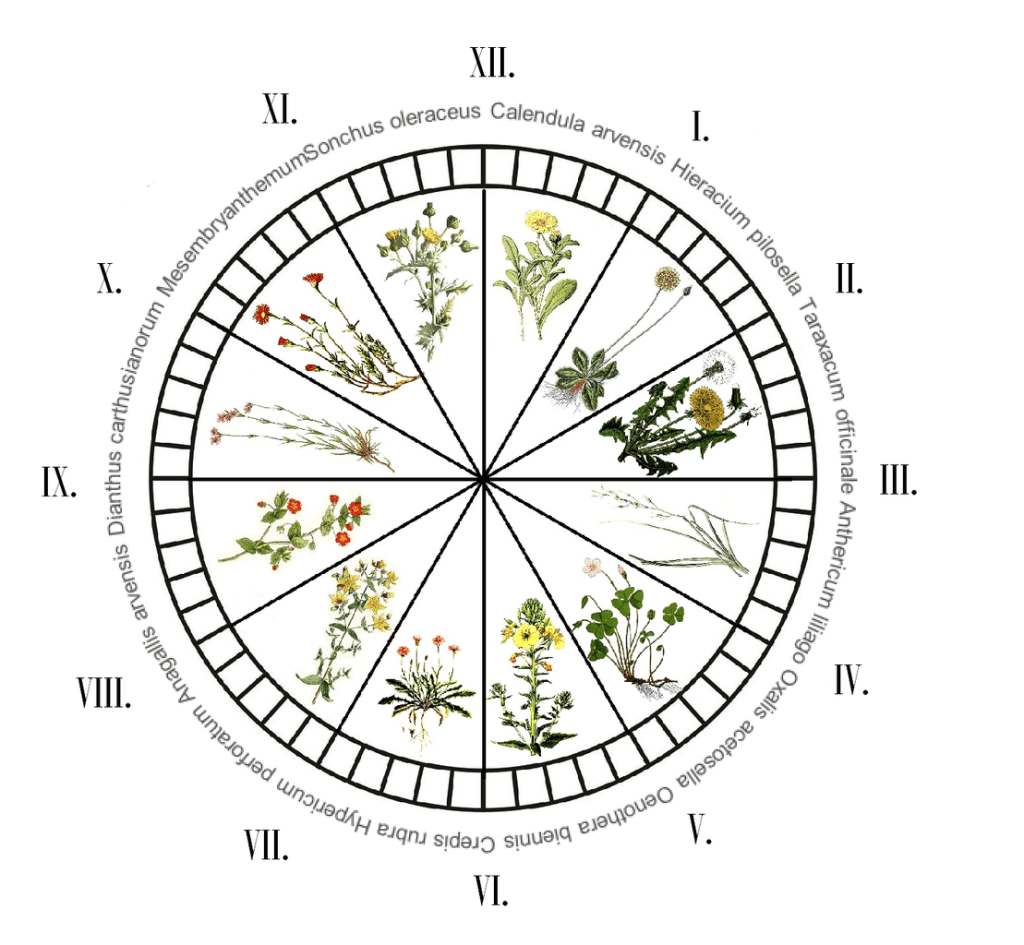

Carl Linnaeus, the 18th century Swedish botanist whose work led to the creation of modern-day biological nomenclature for classifying organisms was the first person to successfully grow a fully flowered banana tree in the Netherlands.

The development of railroads and technological advances in refrigerated maritime transport subsequently enable bananas to become the most traded fruit in the world.

Today bananas are grown in more than 150 countries, and it is widely believed there are more than 1,000 types of bananas produced and consumed in the world. The most common and commercialized type is the Cavendish banana which makes up around 47 of global banana production. This is a high-yielding variety which is also less damage-prone and more resilient in case of natural disasters.

Although we generally describe it as a banana ‘tree’, technically this is not a tree. Bananas, botanically, are considered to be big herbs, because they do not have a woody stem or trunk which is one of the characteristics of a tree. Instead they have a succulent stalk or pseudostem which begins as a small shoot from an underground rhizome and grows upwards as a single stalk with a tight spiral of leaves wrapped around it. Banana leaves are extensions of the sheaths.

To add to the confusion, the banana ‘fruit’ as we call it, is botanically a berry! While we associate berries with small, squishy fruit that is picked off plants, the botanical definition refers to any fruit that develops from a flower containing a single ovary, has a soft skin and a fleshy middle, and contains several seeds. Bananas tick off all these boxes and are thus technically berries!

The botanical kin of bananas include tomatoes, grapes, kiwis, avocados, peppers, eggplants and guavas. Botanically all berries!

Bananas have long been high on the list of ‘super foods’, endorsed from all schools of health from Ayurveda to the newest ‘wellness’ trends. Its versatility was noted even by Linnaeus who envisaged its numerous medicinal values. The banana is literally ‘wholesome’ from A to Z! It is the panacea for all ills from acidity and anaemia, through cramps, depression, mood elevation, PMS, stress relief, and more, all the way to bringing in some zing to tired bodies and minds! Even the banana peel with its blend of acids, oils and enzymes has multiple uses from healing wounds to polishing shoes!

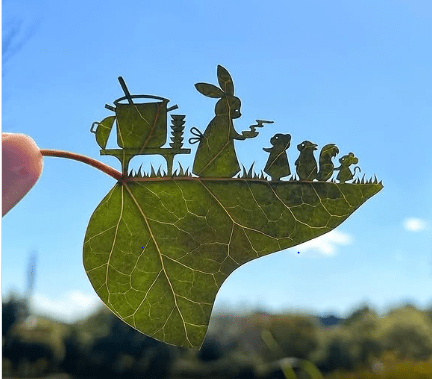

And the banana is a wonderful example of Nature’s perfect packaging. The artful positioning of the individual bananas to form a beautiful cluster or ’hand’ arrangement which can be hung; the tamper-proof skin that protects the soft and perishable flesh within; the nifty top opening that allows for an easy peeling back; and after all that, a covering that does not add to the litter but silently biodegrades to merge back into the soil. No wonder its botanical name is Musa sapientum: the fruit of wise men.

In India the mango always lays claim to being the king of fruits; the solid trustworthy banana is taken much for granted, as it does not make a dashing seasonal appearance and compete for awards of the most varieties and the best of them all. And yet this is the comfort food that is usually on hand, and one that almost every person can afford. It certainly was my father’s favourite, and now is the favourite of his great grandson who endorses Daddy’s maxim of Sabse Achchha Kela (banana is bestest!)

Why this sudden paean to the banana? Well, I discovered that in America, the third Wednesday of April is celebrated as National Banana Day every year (reason for this undiscovered). I decided to join the celebrations this year!

Bananas were first brought to the United States in 1876, for the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. The exotic fruits were wrapped in foil and sold for 10¢ apiece (roughly $1.70 in today’s dollars).

While the mango always lays claim to being the king of fruits, the solid trustworthy banana is taken much for granted, as it does not make a dashing seasonal appearance and compete for awards of the most varieties and the best of them all!

The Banana was my father’s favourite fruit. He always used to say “sabse achha kela!” “Banana is the best”. So true…The scientific name for banana is musa sapientum, which means “fruit of the wise men.”

–Mamata