As the festive season begins, the next few months will see a variety of celebrations. Among the dazzle and din that marks the festivities, there is a quieter celebration going on in several parts of the country. This is the Dragonfly Festival.

Why celebrate dragonflies?

Dragonflies are believed to have been around for more than 300 million years, predating even the dinosaurs. Some of the ancient ones had a wingspan of over two feet! Today we can see only the miniature version of what may have been spectacular creatures, but they are no less charismatic.

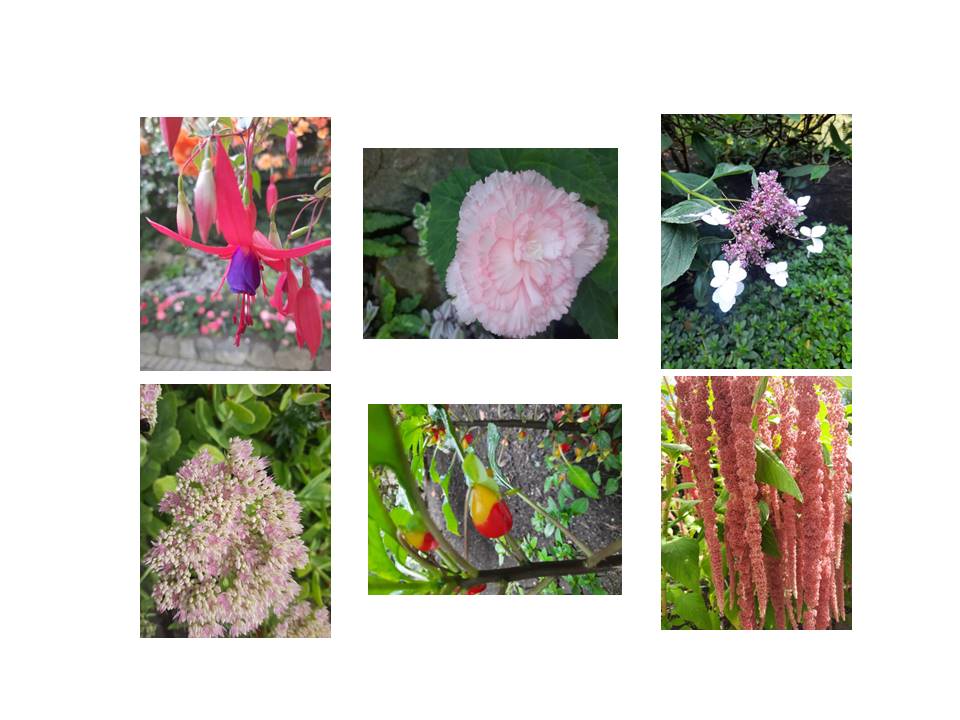

Dragonflies are flying insects; members of the order Odonata. As do most insects, they have six legs, a head, thorax and abdomen which is divided into ten segments. They have four wings, and compound eyes which are made up of thousands of tiny units (ommatidia). Most dragonflies are beautifully coloured with shades of greens, reds, yellows and blues.

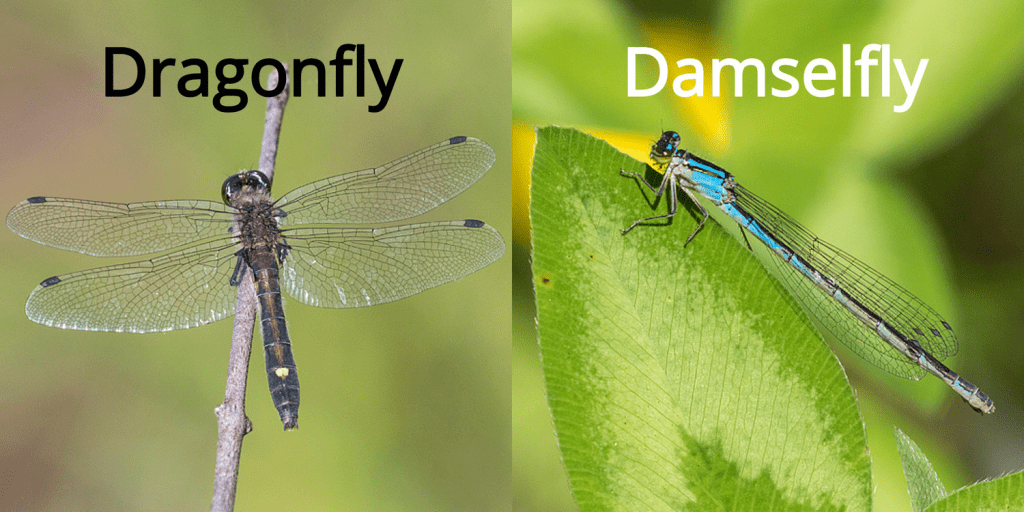

Within the order of Odonata, there are two suborders — dragonflies and damselflies. Although both are commonly called dragonflies, the two are distinct, with the most important difference being the position of the wings when at rest. A dragonfly’s wings will be held separately down at their side while a damselfly will hold its wings together over their back. Damselflies are slender while dragonflies have thicker bodies; and damselflies have two distinct eyes while the eyes of dragonflies typically almost meet in the middle of their head.

The dragonfly life cycle is uneven. The insects lay their eggs on the surface of the water, and the larva that emerges from the eggs is a grayish-brown creature that feeds on aquatic plants and larva of small insects. It remains in the larval stage for most part of its life, shedding the outer layers at regular intervals. For the final shedding it comes out of the water, climbs on a blade of grass, and emerges in its adult form with beautiful wings that make it a swift and graceful flier. It is this magical metamorphosis that has given the dragonfly spiritual associations in some cultures, where it symbolizes transformation and renewal. https://millennialmatriarchs.com/2019/09/24/dragonflies/

Dragonflies are remarkable flyers. When moving forwards they can attain a speed of almost 55 km per hour. They can hover in mid-flight for almost one minute and rotate 360 degrees in place. They can even fly backwards with similar alacrity. Their flying skills and sharp vision aid their hunting technique; they capture prey insects in flight. This has given them the name of Hawks of the Insect World. Adult dragonflies are mainly insect eaters but the nymphs also consume freshwater invertebrates, tadpoles, and even small fish. Being predators both at larval and adult stages, they play a significant role in the wetland food chain. Adult odonates feed on mosquitoes, blackflies and other blood-sucking flies and act as an important biocontrol agent for these harmful insects. They play important ecological roles not only as predators, but also as prey of birds, frogs and other aquatic creatures.

Healthy aquatic ecosystems with strong food chains are critical for dragonflies to survive and thrive. When food sources for dragonflies are affected by the impact of insecticides, this leads to a disruption in the food chain. Which in turn indicates a threat to the larger ecosystem of which those food chains are a part. Thus dragonflies are important environmental indicators; a decrease in dragonfly populations signals that all is not well with the water quality, and in turn the aquatic ecosystem that it supports.

Today, there are more than 5,000 different species of dragonflies and they can be found on every continent except Antarctica. But these are threatened as a result of threats to their habitats. Dragonflies are very sensitive to changes in the environment so change in dragonfly numbers could be an early warning signal of changes in wetlands. There is now increasing consciousness about the vital role of dragonflies, especially with the rapid degradation of wetlands across the world, due to a range of factors including spread of urbanisation, pollution, agricultural practices, and climate change. Conserving dragonflies and their habitat is being highlighted as a priority because they are valuable environmental indicators, including water quality and biodiversity.

The first step to conservation is a greater awareness and better understanding of dragonflies. This can begin with observing these in the context of their habitats, and recording odonate population trends.

India has over 500 species of odonata, with the greatest diversity in the Western Ghats and Northeast India. 196 species in 14 families and 83 genera are known from the Western Ghats. Of this, 175 species are reported from Kerala. Even though India is rich in Odonates, the general public has little awareness of this, nor its significance. Concerned about this, Society for Odonate Studies (SOS), a non-profit organization was formed to impart knowledge to the public about dragonflies and damselflies, and to conduct scientific studies with the objective of conservation of the species and their habitats. The Society created a surge of interest among young naturalists and wildlife enthusiasts in Kerala. SOS joined hands with WWF-India to launch a wider initiative which grew into the Dragonfly Festival.

The Dragonfly Festival started in 2018 to connect citizens with these fascinating creatures, demystify Dragonflies and Damselflies, and celebrate their importance. This is a unique Citizen Science campaign conducted across India which seeks to spotlight the significance and status of dragonflies and damselflies as indicators of healthy ecosystems, and support their conservation. The festival is a collaboration between international, national and local partners which include Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) and Indian Dragonfly Society (IDS) and NBA UNEP, UNDP, Indian Dragonfly Society (IDS) and NBA UNEP, UNDP, and IUCN-CEC. Over the years the initiative has engaged thousands of individuals across several states. In addition to on-ground observation and identification, the festival includes expert sessions, nature walks, competitions, and workshops. This year WWF-India had called for volunteers to conduct regular surveys at a number of wetland locations, and monitor the species over a three-month period. The tasks will include photo documentation, observation and identification. The data will be uploaded on the India Biodiversity Portal.

So many reasons to celebrate dragonflies! And, as India also celebrates Wildlife Week in the first week of October, a reminder that dragonflies and damselflies can be as charismatic as tigers and lions!

–Mamata