Before we started using ‘idk’ for ‘I don’t know’, or ‘rn’ for ‘right now’ or ‘fr’ in place of ‘for real’, was another type of shorthand. A shorthand that people had to spend months to master–the shorthand used by stenographers, the shorthand considered an essential skill in middle class families in the ‘40s and ‘50s. Beginners could take down dictation at 60-80 words per minute (wpm), while skilled professionals like journalists or court reporters, usually could do 100-120 wpm , with experts reaching 160 wpm+! This was no mean feat, as they had to listen, process, and record all at once.

January 4, marked as Shorthand Day or Stenographers’ Day is the birth anniversary of Sir Isaac Pitman, the inventor of the most widely used system of shorthand. Pitman, born on January 4, 1813, in England, developed the phonetic shorthand system that uses symbols to represent the sounds words make, allowing writers to take notes quickly. His motto was “time saved is life gained”.

A History in Shorthand

The story of shorthand begins in ancient Greece, where scribes experimented with symbols to capture speeches. But it was the Romans who elevated it into a fine craft. The best-known system, Tironian notes, is attributed to Marcus Tullius Tiro, the freedman and secretary of Cicero. Imagine him in the Senate, stylus poised, capturing the flights of Cicero’s rhetoric in tiny, elegant symbols at a pace that would daunt even today’s stenographers.

After Rome faded, so did shorthand, only to be revived in Renaissance Europe as printing presses and new bureaucracies demanded speed. From the seventeenth century onward, English-speaking countries became hotbeds of shorthand innovation. Each new system claimed to be the fastest, most logical, most “learnable.”

The Many Styles of Speed

Pitman Shorthand (1837)

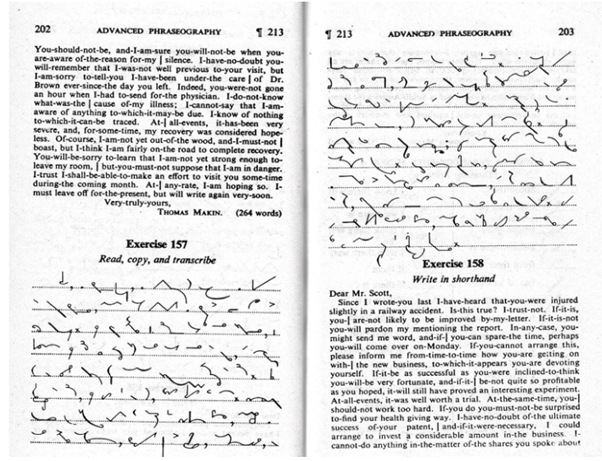

Perhaps the most famous, , Pitman is all about economy of movement. It uses line thickness and angle—thin for “p,” thick for “b”—and trusts that your hand can switch gears mid-stroke. Generations of journalists swore by it, and some still do.

Gregg Shorthand (1888)

An American rival, and the stylish one. Gregg is curvy, loopy, and feels like it was designed by someone who thought in cursive. It became the favourite of secretaries through much of the twentieth century, taught in business schools and tucked into shorthand notebooks everywhere.

Teeline (1968)

The modern British system, simpler and easier to learn. Teeline keeps only the essential letters, streamlining the alphabet without demanding Pitman’s precision or Gregg’s artistic flourish. Journalism schools still teach it.

Stenotype Machines

And then came the tap-dance keyboards—stenotype machines that look like something between a typewriter and a miniature piano. Court reporters can reach 200–250 words per minute with these, a speed human handwriting simply cannot match. Here, shorthand transforms from strokes to chords: multiple keys pressed at once to create whole syllables or phrases.

Shorthand in India: Many Languages, Many Scripts

While shorthand is often associated with English, India has a surprisingly rich tradition spanning Hindi, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Bengali, Urdu, Gujarati, and Malayalam. This diversity is driven by India’s multilingual bureaucracy: courts, legislatures, railways, and administrative offices all needed stenographers who could capture speech in local languages at lightning speed.

Hindi and Marathi were early adopters. The Gopal System of Shorthand, developed by Dr. Gopal Datt Gaur in the 1930s, adapted shorthand principles for Devanagari scripts, making it possible to record Hindi and Marathi speeches with remarkable speed and accuracy. In Maharashtra, government offices and the press used both the Gopal system and Hindi adaptations of Pitman, blending classical shorthand speed with local scripts.

Tamil shorthand took inspiration from both Pitman and Gregg systems, translating their principles into Tamil’s script. Training in Tamil shorthand was common among court and administrative stenographers, and many journals and newspapers relied on it to ensure fast, precise transcription. Telugu and Kannada shorthand followed a similar path, mostly adopting Pitman’s phonetic methods but preserving the unique characters and vowel markers of their scripts. In Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Karnataka, shorthand exams still train stenographers in these systems, though technology has greatly reduced demand.

Bengali shorthand was adapted from Pitman and, to a lesser extent, Gregg. In pre-Independence Calcutta, it was the lifeline of the High Court and newspapers, allowing reporters and clerks to capture speeches and legal proceedings without missing a word.

Urdu shorthand, tailored for the flowing Nastaliq script, helped stenographers in North Indian courts and administrative offices maintain the rhythm and elegance of spoken Urdu while working at high speed.

Gujarati and Malayalam also developed shorthand variants, often Pitman-based. While they never became mainstream, they are proof that shorthand was not a one-size-fits-all skill, but a highly customized craft.

Shorthand Today: Not Gone, Just Quieter

While shorthand no longer fills classrooms the way it did in the 1950s, it has found unexpected pockets of revival. Hobbyists post their notes online. Court reporters remain a highly specialised and respected profession. Some journalists still rely on Teeline, especially when accuracy matters more than verbatim transcripts. And in India, Devanagari, Tamil, Telugu, Bengali, and Urdu shorthand still quietly exist in government stenography courses and niche professional spaces.

It may be a skill worth picking up in the New Year! There’s the quiet power of having a private script. Many of us have kept diaries in shorthand—half secrecy, half aesthetic pleasure. Those swooping Gregg curves or precise Pitman strokes can turn even a grocery list into a small piece of art.

–Meena

What an informative piece to read. I learned it after my 10th-grade vacation, and it helped me take notes in college. A sad reality: I have forgotten how to write.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I think you have to keep practicing!

LikeLike