It is the time of the year when important dictionaries of the English language have just announced their Word of the Year 2023.

Collins Dictionary has picked AI (Artificial Intelligence) the term that describes ‘the modelling of human mental functions by computer programmes’. In other words, a computer system that has some of the qualities that the human brain has, such as the ability to produce language in a way that seems human.

The Cambridge Dictionary has chosen Hallucinate which has traditionally been defined as“To seem to see, hear, feel, or smell something that does not exist, usually because of a health condition or because you have taken a drug.” But is now expanded to include: ‘When an artificial intelligence (AI) hallucinates, it produces false intelligence’.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary’s Word of the Year is Authentic. Authentic has a number of meanings including “not false or imitation,” or “true to one’s own personality, spirit, or character”. It is a synonym of real and actual. It is perhaps an appropriate antidote in an age of Fake News.

To have been selected as Word of the Year means that a word has great resonance for the year in which it was chosen. These are terms that describe the prevailing trends, moods (including anxieties), attitudes, and cultural climate of our time.

Indeed these three words succinctly sum up the year which has been headlined by AI and its potential, including the dangers of false intelligence and fake news, and the growing need to have ‘authentic’ reliable information to draw upon in such times.

The Dictionaries follow a rigorous process leading to the choice. It includes research by hundreds of lexicographers, and now, evidence gathered from millions of new and emerging words of current English from web-based publications, as well as referring to dictionaries themselves, using sophisticated software.

Thus do dictionaries grow, adding words and usages as they emerge in response to changing times and modes of expression. We often forget that the process of creating a dictionary from scratch was, in its time, a complex and gargantuan task, which took years of painstaking manual and mental labour.

The first fully-developed representative of the monolingual dictionary in English is believed to be Robert Cawdrey’s Table Alphabeticall, first printed in 1604. Its first edition had 2543 headwords for which Cawdrey provided a brief definition. While small and unsophisticated by today’s standards, the Table was the largest dictionary of its type at the time.

As the century rolled by, there was a growing feeling that the English language “needed improvement” and that it lacked standardisation. From the mid-17th century many literary figures proposed ideas and schemes for improving the English language, but none really came to fruition. Until Samuel Johnson, an English poet, satirist, critic, lexicographer embarked upon his Plan of a Dictionary of the English Language.

Johnson had several issues with the English language as it was at the time. As he wrote, he had found the language to be ‘copious without order, and energetick without rules’. In his view, English was in desperate need of some discipline: ‘wherever I turned my view … there was perplexity to be disentangled, and confusion to be regulated’.

A group of London booksellers first commissioned Johnson’s dictionary, as they hoped that a book of this kind would help stabilise the rules governing the English language. The booksellers’ interest was purely commercial. They were aware that this kind of work would be popular with the general public, but as such a project would be long and risky, a number of booksellers formed temporary partnerships, thereby sharing the costs as well as the risks. Also the copyright belonged to the publisher, so aside from a one-time payment to the author for commissioning the work, the publishers could enjoy the massive profits from the sales.

In 1746 Johnson entered into an agreement with the booksellers to write an English dictionary, and began work the same year with only six assistants to aid him. A year later he published a plan for the dictionary in which he outlined his reasons for undertaking the project and explained exactly how he intended to compile his work. Johnson projected that the scheme would take about three years, but he seriously underestimated the scale of the work involved. In the end it took him three times this length of time to write over 40,000 definitions and select nearly 114,000 illustrative quotations from every field of learning and literature. Each word was defined in detail, the definitions illustrated with quotations covering every branch of learning. Johnson’s was the first dictionary to use citations for the words it listed. He sourced books stretching back to the 16th century, and used quotations from Shakespeare, Spenser and other literary sources. This was with his intention to acquaint users with the classic literary greats. Johnson was the first English lexicographer to use citations in this way, a method that greatly influenced the style of future dictionaries.

In the process of compiling the dictionary, Johnson recognised that language is impossible to fix because of its constantly changing nature, and that his role was to record the language of the day, rather than to form it.

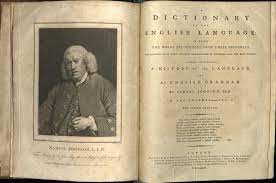

First published in two large volumes in 1755, the book’s full title was A dictionary of the English Language: in which the words are deduced from their originals, and illustrated in their different significations by examples from the best writers. To which are prefixed, a history of the language, and an English grammar. It became popularly known as Johnson’s Dictionary.

The dictionary was a huge scholarly achievement, a more extensive and complex dictionary than any of its predecessors. The closest to compare was the French Dictionnaire which had taken 55 years to compile and required the dedication of 40 scholars. Still, Johnson’s dictionary was far from comprehensive, even by mid-eighteenth-century standards. It contains 42,773 entries, but there were almost 250,000 words in the English language, even during Johnson’s time.

Even as new words are added to the number of dictionaries today, and some of these are crowned as words of the year, here is an educational, and entertaining peek at some of the entries from Johnson’s dictionary. Starting with how he defines himself!

Lexicographer: A writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge that busies himself in tracing the original, and detailing the signification of words. A paltry, dirty, sorry wretch.

Cough: A convulsion of the lungs, vellicated by some sharp serosity.

Distiller: One who makes and sells pernicious and inflammatory spirits.

Dull: Not exhilaterating (sic); not delightful; as, to make dictionaries is dull work.

Excise: A hateful tax levied upon commodities, and adjudged not by the common judges of property, but wretches hired by those to whom excise is paid.

Far-fetch: A deep stratagem. A ludicrous word.

Jobbernowl: Loggerhead; blockhead.

Kickshaw: A dish so changed by the cookery that it can scarcely be known.

Network: Any thing reticulated or decussated, at equal distances, with interstices between the intersections. (See how he defined ‘reticulated,’ below.)

Oats: A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland appears to support the people.

Patron: One who countenances, supports or protects. Commonly a wretch who supports with insolence, and is paid with flattery.

Politician: 1. One versed in the arts of government; one skilled in politicks. 2. A man of artifice; one of deep contrivance.

Reticulated: Made of network; formed with interstitial vacuities.

To worm: To deprive a dog of something, nobody knows what, under his tongue, which is said to prevent him, nobody knows why, from running mad.

Samuel Johnson, was in fact much more than a lexicographer; he was a prodigious writer who published periodicals, plays, poems, biographies and a novel, as well as a celebrated humourist.

–Mamata