The Global Gender Gap Report 2023 is out, and the news is not good for us in India. Well, if you are an untiring optimist who insists on seeing a glass with some drops of water in it as half-full, you will stop me and scold me. For after all, India’s ranking in the list of 146 countries which have been studied, has gone up 8 places, so that we stand at 127th, up from 135th last year.

But for me, as I go through the report, I don’t know see how we can take any comfort from this. Even if we are to view ourselves in a comparative light, we need to pause and consider that Nicaragua and Namibia rank at 7th and 8th, compared to our 127!

The report measures gender gap on four major dimensions: Economic Opportunities, Education, Health, and Political Leadership.

The first bucket, to quote the report ‘contains three concepts: the (labour) participation gap, the remuneration gap and the advancement gap’. The second bucket of Educational Attainment ‘captures the gap between women’s and men’s current access to education through the enrolment ratios of women to men in primary-, secondary- and tertiary-level education’. The Health and Survival sub-index provides an overview of the differences between women’s and men’s health by looking at sex ratio at birth, and the gap between women’s and men’s healthy life expectancy. The last bucket of Political Empowerment measures the gap between men and women at the highest level of political decision-making through the ratio of women to men in ministerial positions, and the ratio of women to men in parliamentary positions.

If we look at India in terms of these dimensions, less than 30 per cent of women participate in the labour market. Women make up 89 per cent of workers in informal sector, which means they are probably underpaid, do not have job security or any other benefits, and work in unsafe, unhealthy and unregulated conditions. Less than 2 per cent firms in India have female majority ownership, and less than 9 per cent have females in top management positions.

Close to 30 per cent women report having faced gender violence in their lives.

We rank 117th in terms of percentage of women in Parliament and 132nd in terms of women in ministerial positions.

That is underwhelming in terms of performance and overwhelming in terms of the task ahead. A practical way to start may be by looking at the factors that are measured to arrive at the rankings. This can probably help a government, an organization and a community and a family work out specific plans and targets.

To get into the details of the employment and economic opportunities segment, the factors include: labour-force participation (including unemployment and working conditions); workforce participation across industries; representation of women in senior leadership; gender gaps in labour markets of the future (including STEM and AI related occupations); gender gaps in skill of the future.

What might that mean for a government? Well, maybe setting targets or incentives/disincentives for public and private sector for employment of women? Importantly government must ensure workplaces, public spaces and transport safe, so that women are able to travel and work without fear. To a large extent, government does walk the talk on gender positions? Many of our Ministries and Departments are headed by women-bureaucrats; the largest public sector bank has been headed by a woman; we have women heading government research labs and scientific institutions, playing a part in our space and nuclear programmes, now full-fledged in the armed forces, etc. But doing this even more aggressively will set an example to the private sector.

What might that mean for a corporation? That they move forward from celebrating Women’s Day to taking a hard look at their policies, systems and culture to see how they can become truly inclusive employers.

What might it mean for educational and training institutions: That they don’t, by action or inaction, deny girls opportunities; that they counsel and encourage them to take up STEM courses and careers.

What does it mean for communities? That they examine their conscious and sub-conscious biases, and understand how these affect their actions; that they make the community safe for girls and women.

And most importantly, what does it mean for a family? That they don’t discriminate against girl-children; that they provide them opportunities; that they don’t belittle their aspirations and abilities; that they don’t deny them their rights; that they help them fight their battles and give them a winner’s mindset.

It’s a long, hard journey. If we aspire to be at least in the top half rather than the bottom half of the ranking,the journey has to begin with every individual—in our hearts, minds and actions, today.

–Meena

https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2023

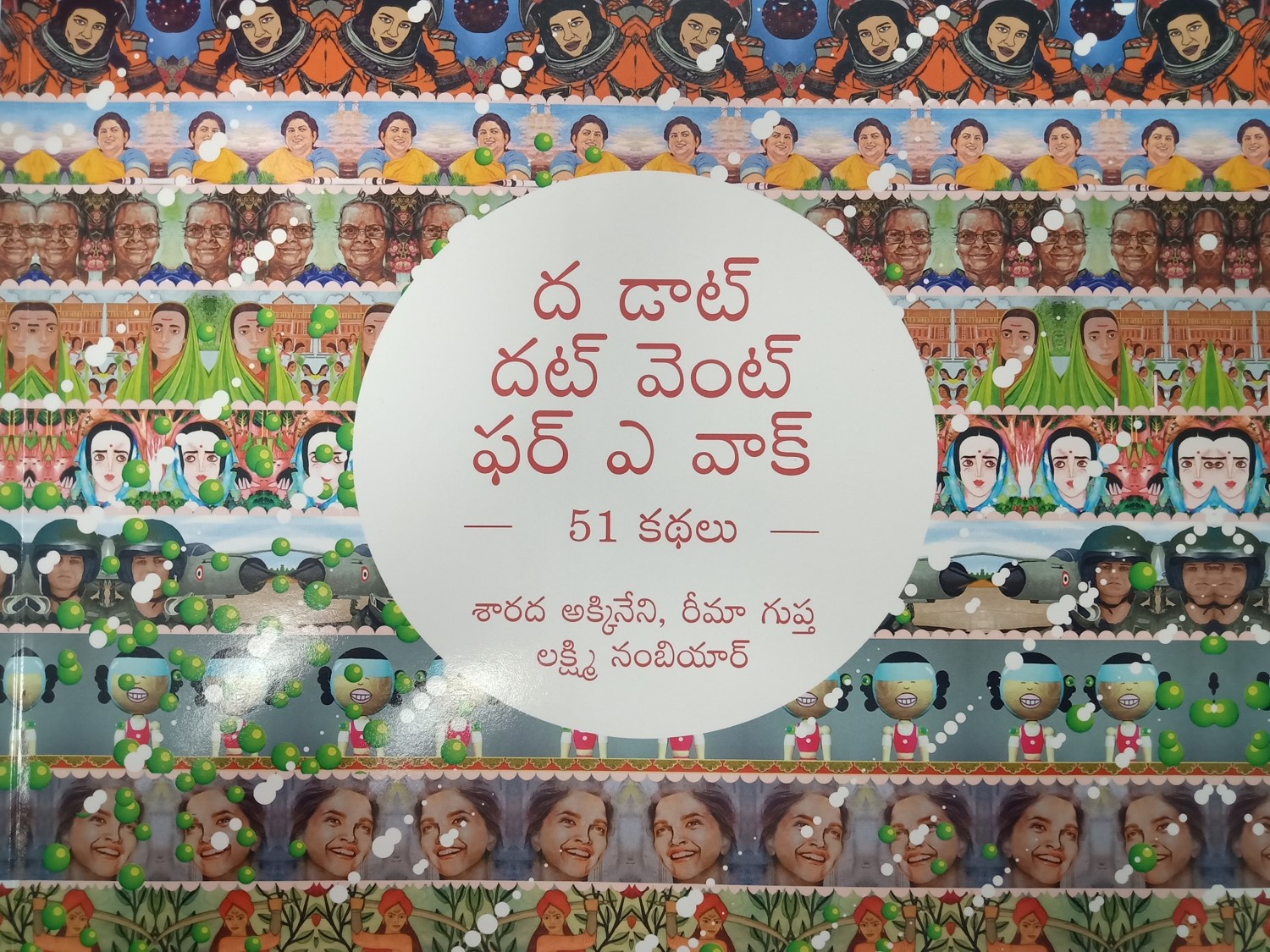

Everything starts with a dot. On a mid-summer day, I got a call from Reema Gupta, who is the co-lead of the Women’s Leadership and Excellence Initiative at Indian School of Business, asking if I could translate the book she had co-authored along with her two friends. The book “The Dot that Went for a Walk” was written in English by Reema and her two friends Sarada Akkineni and Lakshmi Nambiar who have made it a mission to create social change and empower young girls through inspirational stories. Inspired by the quote of artist Paul Klee “A line is a Dot that went for a walk”, the book was titled “The dot that went for a walk”. They wanted the book to be available in regional languages including Telugu.

Everything starts with a dot. On a mid-summer day, I got a call from Reema Gupta, who is the co-lead of the Women’s Leadership and Excellence Initiative at Indian School of Business, asking if I could translate the book she had co-authored along with her two friends. The book “The Dot that Went for a Walk” was written in English by Reema and her two friends Sarada Akkineni and Lakshmi Nambiar who have made it a mission to create social change and empower young girls through inspirational stories. Inspired by the quote of artist Paul Klee “A line is a Dot that went for a walk”, the book was titled “The dot that went for a walk”. They wanted the book to be available in regional languages including Telugu.