No, not a book with dire predictions for 2025 aka Nostradamus, Baba Yaga etc.

The Domesday (or Doomsday) book is the 1200+ year survey record! Covering most of England and parts of Wales, it was commissioned by William the Conqueror. The survey started on Christmas of 1085 (exactly 939 years ago!) and was completed in1086. It is the oldest government record held in The National Archives of the UK.

It is an amazing piece of work, in that it surveyed almost every property in England and Wales. Using a fixed format, the survey tried to elicit who owned which property, who lived there, the livestock, how much the land was worth etc. It traced the history of the property—who had owned it before the time of William the Conqueror and who owned it now.

The whole purpose was to ensure that the King had a record of how much land was owned by whom, and therefore how much tax could be charged! It provides definitive proof of land rights and tax obligations, making it a crucial legal document even today. It covered over 13,000 places. Not only was it a foundational document for land rights, it also the socio-economic landscape of 11th-century England.

But why on earth was it called the Doomsday Book? This evolved from its association with the Last Judgment (or Doomsday). The book was the last word–once recorded, its contents could not be contested! It was the source of evidence of land titles, and hence served as a legal reference for resolving disputes over land ownership. It was the final arbiter!

Data collection for the Book was monumental for its time. Royal Commissioners travelled across the kingdom, collecting information from local juries composed of nobility and citizens convened for the purpose. These people swore in court to give correct and accurate information to the Commissioners. They answered several questions including:

- Who owned the land.

- How much land there was.

- The value of the land.

- The number of tenants and their obligations.

- Livestock counts.

- How many plough teams.

- How much wood, meadow and pasture.

- How many mills and fisheries.

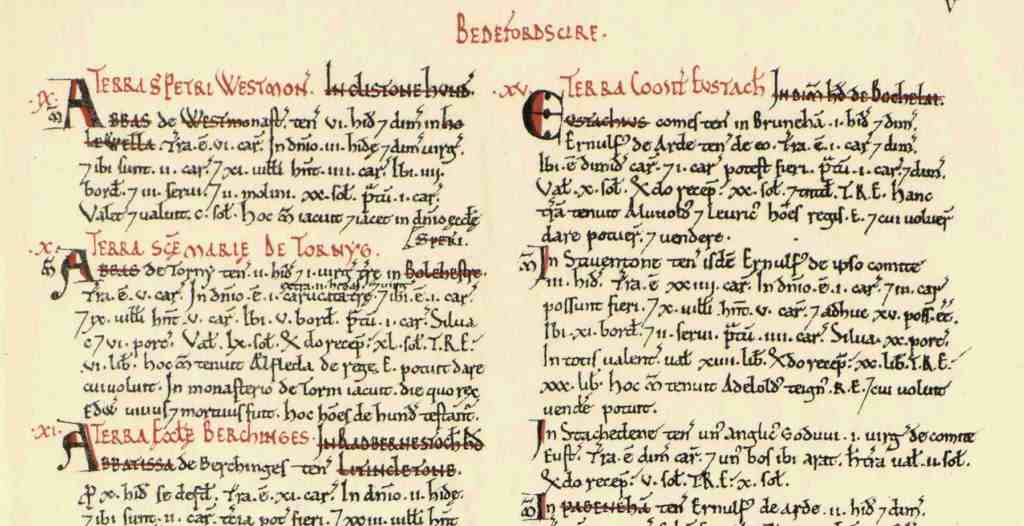

The responses gathered by the juries were meticulously recorded in Latin by one set of scribes, and checked by a second set. The data was probably cross-verified with other records and follow-up inquiries.

The information was recorded in two books—The Great Domesday, and the Little Domesday (covering different geographies). Each is arranged by county, and within each county, by landholder. Each landholder is given a number, which is written in red in roman numerals as the heading of their entry. There is a table of contents at the beginning of each county, which lists the landholders with their numbers.

The Doomsday Book is not a census of the population, but has influenced surveys and censuses down history. The Indian census is considered a model for gathering reliable data across a large country (not of course land ownership—that is a problem yet to be cracked). The Doomsday Book has probably also influenced our census indirectly. Hopefully, we will have our long-delayed census in the coming year—aided by smart phones, tabs and the like. Let us hope the information collected is as authentic as the Doomsday Book managed.

In 1789 Benjamin Franklin said, ” In this world, nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” The Doomsday Book was indeed proof of that!

So here is to a Happy 2025, even though we will still have to pay our taxes!

–Meena

nationalarchives.gov.uk

Pic: Historic UK