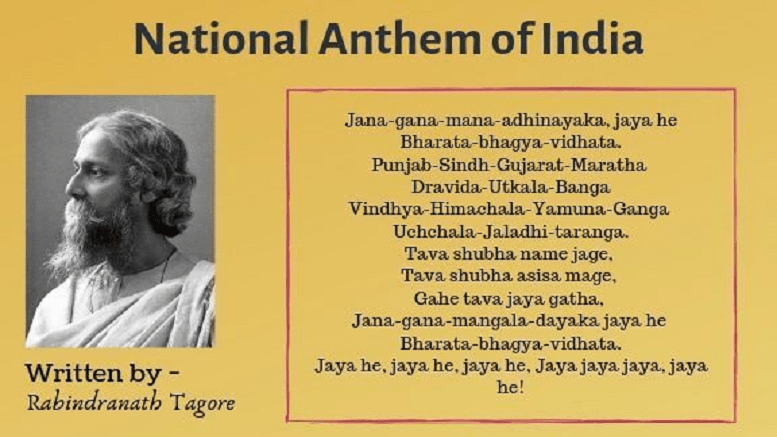

A few weeks ago, India celebrated Republic Day. It was, as always, a solemn occasion. For us, Republic Day marks the day when we adopted our Constitution and became a Republic.

But not all Republic Days are solemn. Nor do they come every year. Whangamōmona, a small settlement in rugged New Zealand’s North Island, celebrates Republic Day in January, but only every two years. It last celebtrated its Republic Day on Jan 18, 2025, marking 36 years of independence. Hundreds of visitors attended the event, which featured rural activities, a sheep race, presidential elections

Whangamōmona has a funny backstory. It seceded from New Zealand. How and why did this come about?

In 1989, New Zealand restructured its local government boundaries. For decades, Whangamōmona had been part of the Taranaki region. But the reforms shifted it into the Manawatū-Whanganui region instead. On paper, this was administrative housekeeping. On the ground, it felt like cultural displacement.

The town identified economically and socially with Taranaki. Farming networks, community ties, supply routes were all there. But suddenly, they were told they belonged somewhere else.

So on 1 November 1989, in response to what they saw as distant bureaucratic meddling, Whangamōmona declared itself an independent republic.

But this wasn’t angry secession. It was satire with a straight face.

The Republic of Whangamōmona established:

- A president

- A passport (yes, you can get it stamped)

- A national day

- And a constitution — loosely interpreted

The tone was tongue-in-cheek, but based very much on community pride. Every two years, on Republic Day (in January), thousands of visitors descend on this tiny town of fewer than 50 permanent residents. There are sheep races. Gumboot throwing. Debates. Parades. And, most importantly, the presidential election.

The candidates over the years have included:

- A goat (Billy Gumboot)

- A poodle

- A human (briefly)

- And even a tortoise

A race to choose the President

Billy Gumboot, the goat, was perhaps the most iconic president. He reportedly served with dignity until his untimely death in 1999. His successor? Tai the poodle.

Isolation as Identity

Whangamōmona isn’t easy to get to. It lies along the Forgotten World Highway — which is honestly one of the best road names ever conceived. The route winds through dramatic hills, misty valleys, and farmland that feels cinematic in its remoteness.

In the early 20th century, Whangamōmona was a frontier settlement, established during railway expansion. It once had a hotel, a school, a hall, and enough settlers to sustain real momentum.

Then the railway declined. Young people left. Farms consolidated. The population shrank.

Like many rural communities worldwide, it faced the existential question: how do you survive when the economic centre shifts away?

Whangamōmona’s answer was genius: if you cannot compete on scale, compete on story.

The “Republic” became a brand. Visitors stop at the Whangamōmona Hotel (the town’s social nucleus), get their passports stamped, and take photos with the republic signage.

Instead of being “a place left behind,” Whangamōmona became “that place bold enough to declare independence.”

Why This Tiny Republic Matters

In a world where declarations of independence are usually soaked in conflict, Whangamōmona offers something softer: protest through humour.

It reminds us that governance is, at some level, a social agreement — and that local identity matters deeply. The town’s mock-secession wasn’t a rejection of New Zealand. It was a wink at centralised decision-making.

There is no bitterness in it now. Only tradition.

Republic Day is less about rebellion and more about reunion. Former residents return. Visitors become temporary citizens. The town swells with life.

For one weekend, the population multiplies many times over. And the republic thrives.

Who gets to decide where we belong?

Sometimes the answer is: we do.

And maybe that’s why this story resonates so widely. It’s about scale — how small places can assert symbolic power. It’s about humour as strategy. It’s about community cohesion in the face of administrative indifference.

Whangamōmona could have quietly faded into obscurity. Instead, it elected a goat.

That choice tells you everything.

A funny story with profound lessons about identity and self-assertion.

–Meena