Kuldhara is on the tourist map of Jaisalmer district. On the way to Sam where the desert starts, is this ‘ghost town’ abandoned by its inhabitants about 200 years ago. The history of the town goes back to the 13th century when it was first settled by Paliwals, people from Pali district. Over the centuries, it grew into a prosperous place, with about 400 houses and over 1500 inhabitants at the peak. It had a pond, Udhansar, excavated by one of the first inhabitants, and at least one temple dedicated to Vishnu, as well as several wells and a step-well. It is actually a planned city, with proper layouts and a place for everything.

Till it was suddenly abandoned. It is not clear why the inhabitants left, but many reasons are given. Was it dwindling water supplies? Was it an earthquake? Or, more dramatically, was it the unwanted pursuit of one of the beautiful girls of the town by a local minister?

Well, whatever the reason or combination of them, it is a fact that people started leaving the place, probably not fleeing overnight as the tourist guides will tell you, but probably in trickles.

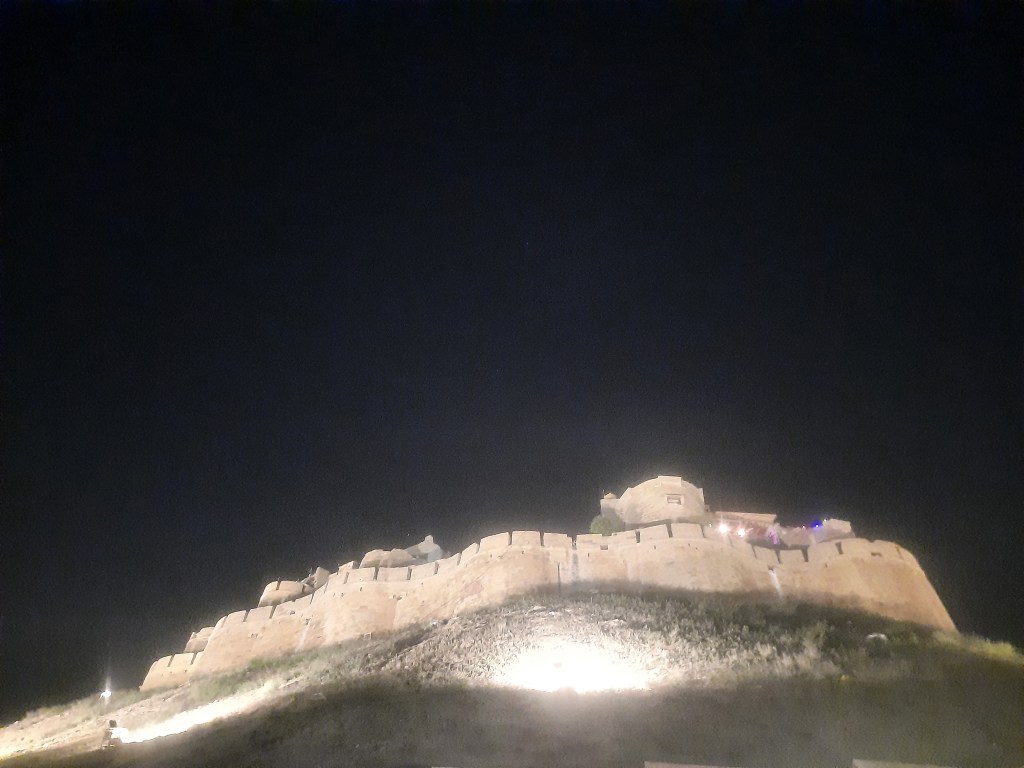

The mud-brick houses, temple and various other structures still stand in fairly good condition. Local legend of course goes that the township is haunted, and visitors are assured it is a dangerous place at night! The legend also says that the Paliwals while leaving the place, placed a curse on it, saying that anyone who tried to occupy it would meet dire consequences. All this led to its attracting tourists.

The Rajasthan government decided to develop this as a tourist site around 2015. This is definitely a strategic move, given that it is just 18 kms away from Jaisalmer, and makes for a comfortable half-day trip, and it had already gained notoriety for its ghosts.

It is well-maintained by the Archeological Survey of India. There are of course guides. And importantly, fairly clean toilets. To this day, the neighbouring villages insist the gates be closed in the evening, so the Kuldhara ghosts don’t wander into their houses!

Of course, a lot more could be done—more signage, re-creation of a typical house, visualization of the town as it must have originally been, a more serious delve into the reasons for its abandonment, etc.

All of this will hopefully be done by the authorities in due course.

But an extremely disturbing incident that happened last week brings to fore the need for us as citizens and tourists to be more responsible. Newspapers report on a video that went viral. The video shows two tourists holding hands and kicking down the ancient brick wall of one the houses in Kuldhara. They were apparently doing this for putting up the video on social media.

The police are waiting for a formal complaint to be filed before taking action. Hopefully, this will be done fairly soon and action will be taken. The penalty for those who deface structures of national and historical importance has fortunately been enhanced in 2010 vide an amendment to the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act. Now, such vandals will have to face imprisonment up to 2 years and/or a fine of up to Rs. 1 lakh.

Sadly, very few cases actually come to the stage where the punishment is given. Often, even the FIR is not registered—though in this case, the police seem to be ready to do this.

Kuldhara is just the latest example—from tourists knocking down pillars at Hampi to graffiti in Golconda, we have a long sad story of vandalism at cultural heritage sites. If our monuments are to have a chance, punishment in these cases needs to swift, exemplary and well-publicized. Maybe there needs to be a sign outside the monument as to how someone tried to vandalize and what punishment they got!

And of course our educational institutions need to instill respect for our cultural and natural heritage, and strongly din home the need to take the greatest care of them.

The responsibility rests with each and every one of us.

–Meena