May 10 is celebrated as Cactus Day in the US. It is “a day dedicated to recognizing and appreciating the unique and fascinating world of cacti. This day also serves as a reminder of the many cactus species facing extinction and the need for their conservation, especially in their natural habitats.” Cacti are flowering plants that produce seeds. They are able to bloom every year, but they will produce an abundance of flowers in response to heavy rains. The family Cactaceae comprises many species of flowering plants with succulent (water-storing) stems.

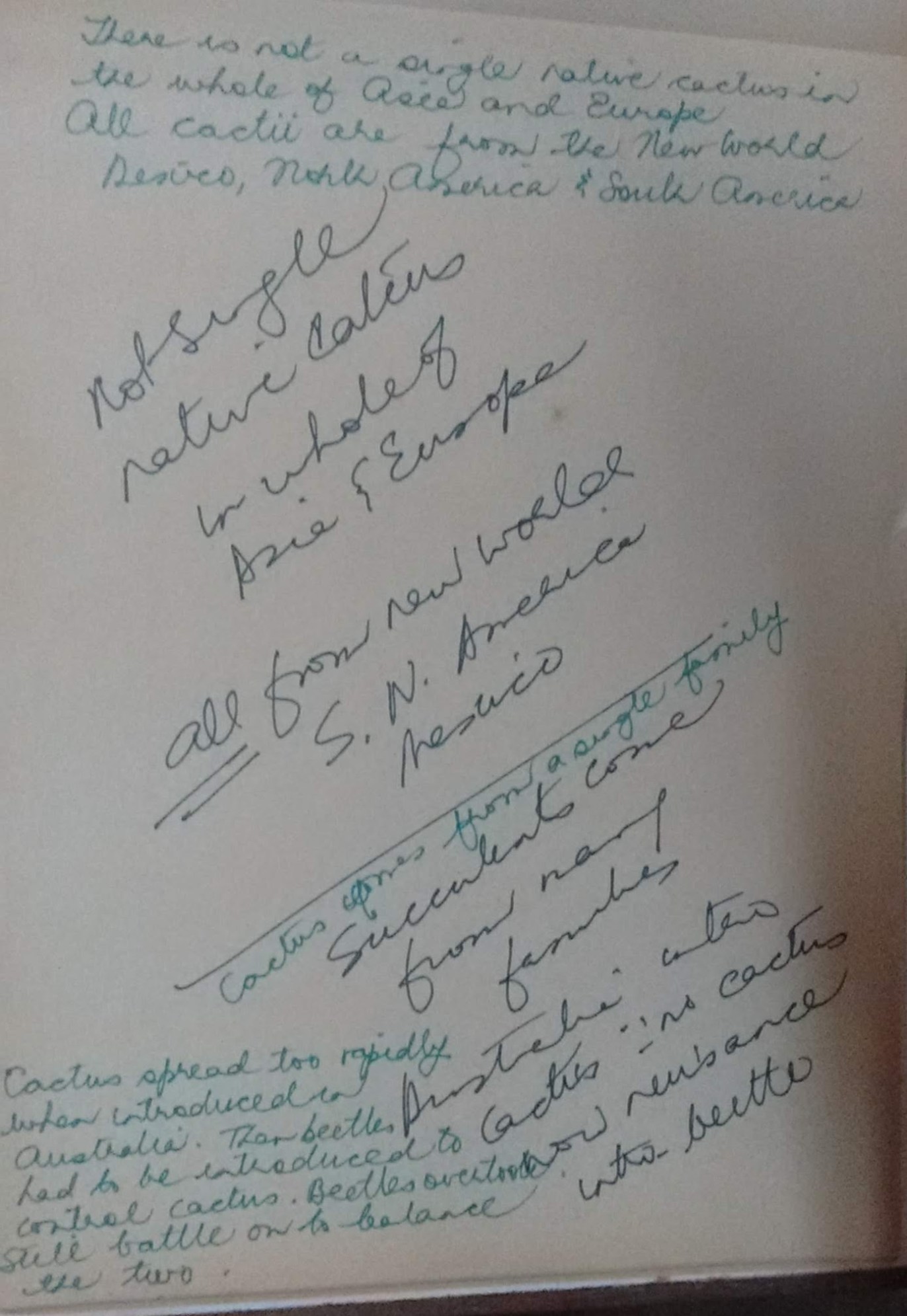

It is entirely appropriate that it is a day marked in the US. Because 1749 out of the known 1750 species of cacti are native to the Americas! In other words, cacti were not originally found in any other part of the world.

I have to admit, this kind of blew my mind. All of us, from the time we are children, when asked to draw deserts or make an exhibit around the theme, have always generously populated our deserts with our own versions of cacti.

But cacti occur naturally only in the Americas–from Patagonia in South America, through the US, to parts of Canada. Anywhere else we see them, they have been taken by humans.

There are however equivalents in other parts of the world. There are the Euphorbs, tamarisks, saltbrushes etc. in Africa, and succulent and spinifex grasses in Australia. In India we have khejri, thoor, acacias etc. all of which grow in our deserts. But these are not cacti. All them have various adaptations to dry conditions like small or no leaves, spines, thick stems and deep roots. But they differ from cacti in that they do not have areoles. The presence of a structure called the areole is what sets cacti apart from all other plants. Areoles are round or elongated, often raised or depressed area on a cactus which is equivalent to a bud and from which spines, flowers, stems, or roots grow.

Cacti were introduced to Europe by, no surprises, Christopher Columbus. In 1493, on his second voyage to the Americas, he brought back a specimen of the prickly pear—the first time a cactus was seen in Europe. It caught the fancy of botanists, horticulturists and the public, and led to widespread cultivation of these plants.

They came to India with the Europeans, most likely sometime in the 16th or 17th century. In recent times, there has been much interest in these plants. They are much prized for their dramatic looks and are a feature in every balcony garden and indoor succulent-tray. At a commercial level, the dragon fruit, cultivated widely across the country and now found in roadside fruit stands everywhere, is a cactus. Known as pitaya or pitahaya, it is native to southern Mexico, Central America, and parts of South America. It is a climbing cactus species. The fruit is low in calories, rich in antioxidants and is said to have many other wonderful properties. But frankly, I am yet to get used to the bland taste!

For a few years now, our Central Arid Zone Research Institute (CAZRI), and ICARDA, an international organization, have been experimenting with cultivation of cacti, with a view to using it as fodder. Cacti as a fodder crop is seen as having the potential to help in the widespread shortage of green fodder, particularly during the summer months in many parts of the country. While still in experimental stages, it is thought to have some possibility.

India also has large and scientifically significant cacti collections. The National Cactus and Succulent Botanical Garden and Research Centre is located in the city Panchkula, the satellite town of Chandigarh. It is spread over seven acres and houses over 2500 species of cacti and succulents. The Regional Plant Resource Centre at Bhubenehswar has Asia’s largest collection of cacti. This Centre has created 200 new varieties and hybrids of cacti by breeding, growth manipulation, etc.

We said at the start that all except one cactus species was native to the Americas. The one exception is Thipsalis baccifera also know as the mistletoe cactus, which occurs naturally not only in the Americas, but also Africa, Madagascar, and close home in Sri Lanka. Scientists are still figuring out the how and why of this exception.

So look at cacti with new eyes. Love them, but don’t hug them!

-Meena

In the blazing yellow heat

In the blazing yellow heat