Last week I was ruminating on KK Shailaja and her refusal of the Magsaysay award. She is not alone. There are several people across the world who for principles or personal choices refuse awards.

Arguably the most prestigious award in the world is the Nobel. But there are two people who have refused the Noble too.

The first was the author Jean-Paul Sartre, who in principle refused all official awards. He declined the 1964 Literature Prize, stating: ‘A writer must refuse to allow himself to be transformed into an institution, even if it takes place in the most honourable form.’

The other person who refused the Nobel was Le Duc Tho of North Vietnam. He and Henry Kissinger were awarded the 1974 Peace Prize together ’for jointly having negotiated a cease fire in Vietnam in 1973’. However, Le Duc Tho refused the award ‘on the grounds that his opposite number had violated the truce’. He said ‘peace has not yet been established’.

Russian mathematician Grigori Perelman’s reason for declining the Fields Medal, considered the Nobel of mathematics, was similar to Jean-Paul Sartre. He said that he had no interest in money and fame and did not want to be on display like a zoo animal. Considering that the inaugural award was $1-million, that was a brave stand.

Protest against governments is often a reason to refuse awards. For instance, Arundhati Roy, Booker-winning novelist, refused the Sahitya Akademi Award for her collection of political essays The Algebra of Infinite Justice saying she could not accept an award from an institution supported by the Indian government, whose policies on “big dams, nuclear weapons, increasing militarization and economic liberalism” she disagreed with.

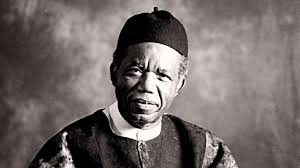

Another author who refused an award from his government was the renowned novelist Chinua Achebe. Nigeria offered him the ‘Commander of the Federal Republic’. But Achebe in a letter to the then-president Olusegun Obasanjo expressed his great discomfort with events in Nigeria. His letter said ‘I had a strong belief that we would outgrow our shortcomings under leaders committed to uniting our diverse peoples. Nigeria’s condition today under your watch is, however, too dangerous for silence.’ He again turned down the honour again in 2011

Not against the government, but Marlon Brando registered his protest against the establishment—in this case Hollywood. He refused the Oscar for Best Actor for the film Godfather in 1973, citing the ill-treatment of native Americans by the film industry as the reason.

Several Indians have refused the government’s high honours for several reason. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, freedom fighter and our first Education Minister declined the honour, taking the principled stand that those who were on selection committees for national honours should not themselves receive them.

PN Haksar bureaucrat and diplomat who served as Principal Secretary to the PM was offered the Bharat Ratna in 1973 specially in the light of his role in brokering the Indi-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, as well as the Shimla Agreement. He declined saying ‘Accepting an award for work done somehow causes an inexplicable discomfort to me’. Some other civil servants have also taken this stand.

A communist who probably set the standard for KK Shailaja was EMS Namboodiripad, General Secretary of the CPI (M) and the Kerala’s first Chief Minister who declined the 1992 Bharat Ratna–he said it went against his nature to accept a state honour.

Some others like Swami Ranganathananda have declined awards because it was given to them as individuals, and not to the organizations that they were part of—in this case, the Ramakrishana Mission.

Two prominent journalists—Nikhil Chakravarty and K. Subrahmanyam (who was also a civil servant)—refused Padma Bhushans because they thought it was not appropriate for journalists to accept awards from the government. As Nikhilda put it ‘journalists should not be identified with the establishment.’

Romila Thapar the distinguished historian refused to accept the Padma Bhushan twice. Her stand was that she would accept awards only ‘from academic institutions or those associated with my professional work.’

Several distinguished people have refused or returned honours due to specific incidents, as a mark of protest against the government. These include Hindi author and parliamentarian Seth Govind Das, and Hindi novelist and playwright Vrindavan Lal Varma, both protesting against the amendment of the Official Languages Act to allow for the continued official use of the English language. The famous Kannada novelist Shivram Karanth returned his award to protest against the declaration of Emergency. PM Bhargava, scientist and founder-director of Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology returned his award in protest of the Dadri mob lynchings and out of concern at the ‘prevailing socio-political situation’ in the country. Prakash Singh Badal ex-CM Punjab, and SS Dhindsa leader of the Shiromani Akali Dal (Democratic) party, returned their awards to show their support to the Farmers’ protests.

Some return awards because they feel the recognition has been delayed too long, or because they feel that people junior to them have been recognized before them. These include playback singer S. Janaki who felt it came too late. Sociologist GS Ghurye refused his award because he felt that people who had contributed less had been given more prestigious awards.

Whatever the reasons, when people of achievement refuse or return awards, governments and establishments need to seriously listen to the reasons. If they think the person is worth honouring, surely the point that they make by refusing the award must be worth listening to?

–Meena