Jane Goodall’s story begins, as many extraordinary stories do, with an ordinary girl and an unlikely dream. As a child in England, she carried a toy chimpanzee named Jubilee everywhere. No one could have guessed that this early fascination would lead her to the forests of Gombe, where she would change not just how we look at chimpanzees, but also how we think about our relationship with nature.

When Jane set off to Africa in 1960, she had no formal scientific training. What she did have was patience, an open mind, and an eye for detail. Those qualities led to her ground-breaking observations: chimpanzees using tools, showing complex emotions, and displaying social bonds once thought to be uniquely human. These revelations turned the world of primatology upside down, but more importantly, they shifted how the public perceived animals. No longer were chimpanzees just “creatures” in the wild; they were kin.

Jane Goodall was truly path-breaking as a woman scientist at a time when the field of primatology, and indeed most of science, was dominated by men. In the early 1960s, she ventured into the forests of Gombe, Tanzania at a time few women undertook intensive fieldwork. For countless young women, she became a role model who showed that passion and persistence could break barriers, and that it was possible to be both rigorous and compassionate in research. By sharing her journey widely, she inspired generations of women to believe that they, too, could pursue careers in science, venture into the field, and shape the questions that redefine our understanding of the natural world.

Jane’s greatest contribution may not lie in her scientific discoveries alone. It lay in how she chose to use them. From the 1980s onwards, she began to move away from research and into advocacy and education. She saw forests vanishing, wildlife populations declining, and young people growing increasingly alienated from nature. She knew that science alone could not stem the tide of environmental degradation. What was needed was education—education that could inspire empathy, action, and hope.

This vision gave birth to Roots & Shoots, her global program for young people. Starting in 1991 with just a handful of students in Tanzania, it has now spread to more than 60 countries, empowering thousands of young people to become change-makers in their communities. The premise is simple: every individual matters, every individual has a role to play, and every individual can make a difference. Roots & Shoots projects range from planting trees and cleaning up neighbourhoods, to wildlife conservation and social justice initiatives. Jane wanted children to see themselves not as passive inheritors of a troubled world, but as active participants in shaping a sustainable future.

Her approach to environmental education is distinctive in three ways. First, it is grounded in hope. At a time when climate anxiety is widespread, Jane insists that hope is not naïve optimism, but a call to action. “Without hope,” she says, “we fall into apathy. With hope, we find the courage to act.” Second, she emphasised connection—to animals, to the land, and to each other. In her talks across the globe, she reminded audiences that the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems is intertwined. And third, she led by example. Even in her late 80s, Jane travelled around the world, tirelessly addressing schools, communities, and governments, showing that passion has no retirement age.

What makes Jane Goodall so compelling as an educator is that she does not lecture; she told stories. She talked about the moment when a chimpanzee she named David Greybeard accepted her presence, breaking the barrier between human and animal. She recalled village children in Tanzania planting trees that now tower above their schools. Through these narratives, she drew her listeners into a shared emotional space where science and spirit met.

For us, as parents, teachers, and citizens, there is much to learn from her style. Environmental education, she shows us, is not about overwhelming children with statistics on melting ice caps. It is about nurturing wonder, building empathy, and giving them the tools to act. It is about ensuring that the animals the children see today do not become just relics of lost species tomorrow.

Jane Goodall often said that every day we make an impact on the planet, and we can choose what kind of impact that will be. That simple truth is perhaps her most enduring lesson. She taught generations not only how to care about the environment, but also how to carry that care into action.

In a world crowded with crises, Jane stands as a reminder that education is not about filling minds, but about lighting fires. And hers is a fire that continues to spread, quietly but persistently, across classrooms, living rooms, and communities worldwide.

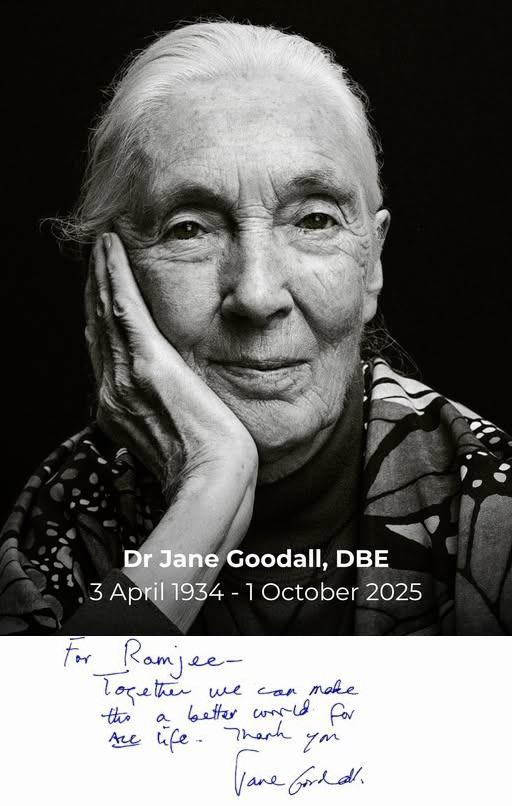

When I worked at Centre for Environment Education, I was lucky enough to meet her to introduce the institution and its work to her. She had very little time, but focussed intently on the conversation. It was indeed a memorable moment!

Thank you Jane Godall for all you have done and all the people you have inspired. RIP.

–Meena

PIC: My ex-collegue Ramjee is lucky to have got this signed pic of her’s when he met her.

Brilliant

Brilliant

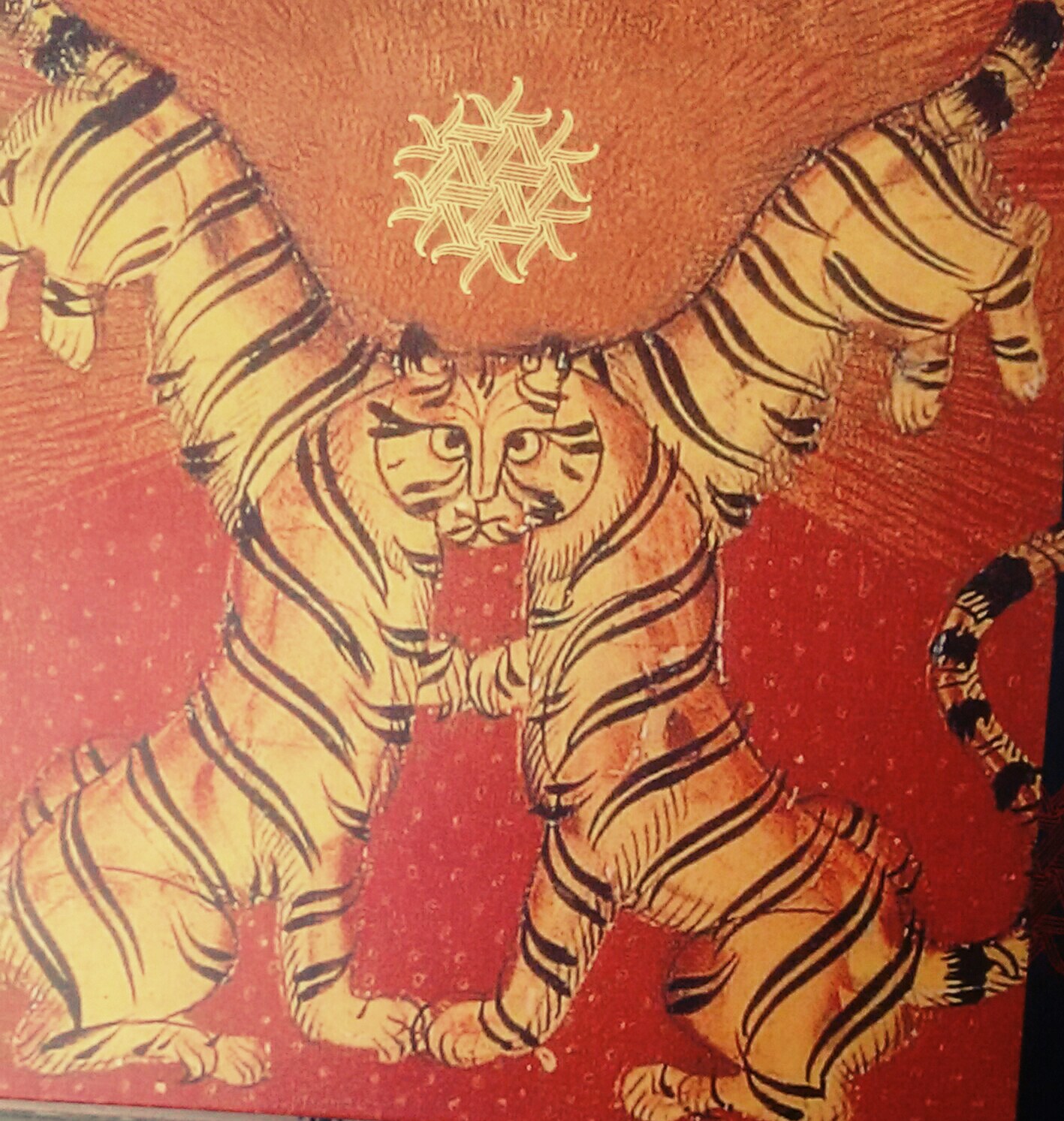

ll agog with the news that a Tiger has been spotted within its political boundaries. Papers are full of speculation about where it came from and where it went. In the meanwhile the state has quickly laid claim to be the only one in the country with three big cats—lion, leopard, and now tiger!

ll agog with the news that a Tiger has been spotted within its political boundaries. Papers are full of speculation about where it came from and where it went. In the meanwhile the state has quickly laid claim to be the only one in the country with three big cats—lion, leopard, and now tiger!