Clay tablets from Mesopotamia mention this deadly disease. Indian writings of the Vedic period (1500 to 800 BC) call it the ‘king of diseases.’ Traces of the disease have been found in remains of bodies from Egypt dating from 3200 and 1304 BC. The 270 BC Chinese medical canon has documented the disease’s headaches, chills, fevers and periodicity. The Greek poet Homer (circa 750 BC) mentions it in The Iliad, as do Aristotle (384-322 BC), Plato (428-347 BC), and Sophocles (496-406 BC) in their works.

The disease? None other than malaria, a disease that has taken its toll on not only humans down the ages, but our Neanderthal ancestors too. In the 20th century alone, malaria claimed between 150 million and 300 million lives, accounting for 2 to 5 per cent of all deaths!

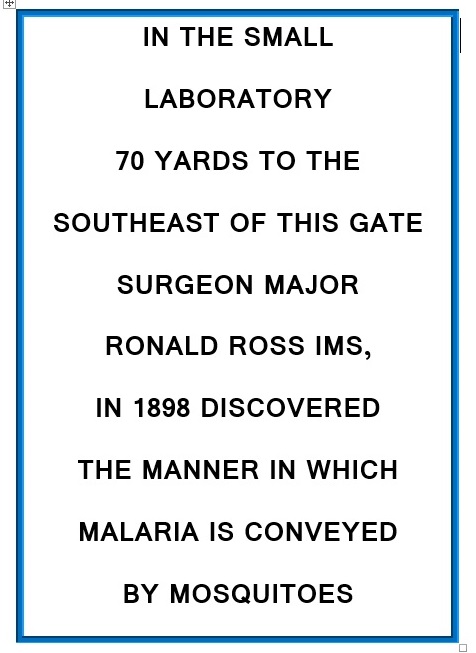

Many have been the scientists who spent their lives trying to understand malaria. Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (1845-1922) a French army doctor during the Franco-Prussian played a key role. He as the first to postulate that malaria was not spread by bad air, but rather that ‘Swamp fevers are due to a germ’. He was also the earliest scientist to detect crescent-shaped bodies in the blood of affected individuals, and then the four stages of the development of the parasite in the blood. These findings were confirmed by Camillo Golgi. Dr. Charles Ross and India played a huge part in the unravelling of the whole cycle and Ross received the Nobel Prize for discovering the mosquito-stages of malaria.

The story of uncovering the cure for malaria has been dramatic too. For centuries, when no one had a clue what caused malaria, treatments included blood-letting, inducing vomiting, and drastic things like limb amputations, and boring holes in the skull. Herbal medicines like belladonna were used to provide symptomatic relief.

But the cure strangely came from South America—a region not originally plagued with the diease. It was probably brought from the outside around the 16th century. The native Indians were the first to discover the cure. The story goes that an Indian with a high fever was lost in the Andean jungles. Desperate with thirst as he wandered the jungles, he drank from a pool of stagnant water. The taste was bitter and he thought he had been poisoned. But miraculously, he found his fever going down. On observation, he found that the pool he had drunk from had been contaminated by the surrounding quina-quina trees. He put two and two together, and figured that the tree was the cure. He shared his serendipitous discovery with fellow villagers, who thereafter used extracts from the quina-quina bark to treat fever. The word spread widely among the locals.

It was from them that Spanish Jesuit missionaries in Peru learnt about the healing power of the bark between 1620 and 1630, when one of them was cured of malaria by the use of the bark. The story goes that the Jesuits used the bark to treat the Countess of Chinchon, the wife of the Viceroy who suffered an almost fatal attack. She was saved and made it her mission to popularize the bark as a treatment for malaria, taking vast quanitities back to Europe and distributing it to sufferers. And from then, the use of the powder spread far and wide. It is said that it was even used to treat King Louis XIV of France.

The tree from which the bark came was Cinchona, a genus of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae which has at least 23 species of trees and shrubs. These are native to the tropical Andean forests. The genus was named so after the Countess of Chinchon, from the previous para. The bark of several species in the genus yield quinine and other alkaloids, and were the only known treatments against malaria for centuries, hence making them economically and politically important. It was only after 1944, when quinine started to be manufactured synthetically, that the pressure on the tree came down.

Not unusually, the tribe who actually discovered it is forgotten. The medicine came to be called “Jesuit Powder’ or ‘Chincona powder’ or “Peruvian powder’. Trees in the genus also came to be known as fever trees because they cured fever.

May the many indigenous community, their knowledge and their practices which are at the base of so many medicines today get their due recognition, credit and due.

–Meena