Today, each one of us harbours doubts and fears about the rapid rise of Generative Artificial Intelligence (Gen AI), smart robots, driverless cars etc., especially whether these will take away jobs from people and give them to machines.

This has happened with every new technology since the industrial revolution. Maybe the time of maximum anxiety around technology and jobs was in the late 1700s to early 1800s, a time when quite a few people in the UK depended on the cotton, wool and silk industries for their livelihoods. This was based on the labour of framework knitters, who like some of our weavers even today, worked in their own homes. Though the hours were long and they got small wages, they were at an equilibrium.

In the early 1800s, there were around 30,000 knitting-frames in England. But change had already started to set in. Change of fashion (men moving from stockings to trousers) and increasing exploitation of weavers by the middlemen were two major factors. But perhaps the most important was the mechanization and wide-frame machines that were coming in to make production faster. Production moved from homes to factories with this mechanization.

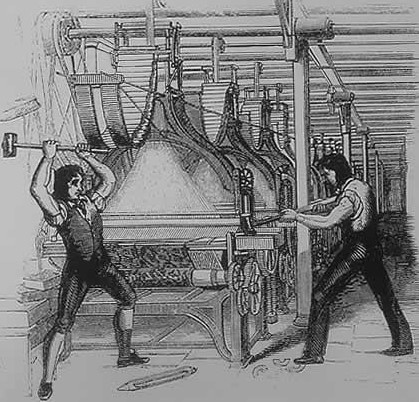

As more and more people lost their livelihoods, anger and frustration boiled over, and mill-owners and the new machines were targeted. The scale of the sabotage that occurred in England between 1811 and 1816 was beyond anything seen before. In the peak three months of the riots, 175 of these new frames were broken per month! The people involved in these riots and destruction called themselves ‘Luddites’. The origin of the name is not quite clear, but some said it was after Ned Ludd, a legendary weaver who in 1770 was supposed to have smashed such machines.

Governments then, as today, were heavy-handed. Their response to the riots was to pass the Frame-Breaking Bill in the House of Commons in February 1812. The Bill was drastic– it proposed transportation or the death penalty for those found guilty of breaking stocking or lace frames. Not everyone was happy with the draft Bill– in the House of Lords, the poet and social campaigner Lord Byron argued against it saying that it was placing the value of life at “something less than the price of a stocking-frame”. But such passionate appeals did not help, and the Bill was passed.

The Government would have expected all such riots to stop after the Bill. But exactly the opposite happened. The riots actually became more violent and rioters started using arms. The logic was that if they were going to be punished by death or deporatation for breaking frames, then they might as well do something that really deserved such drastic measures. A popular rhyme at the time was “you might as well be hung for death as breaking a machine”. A few mill owners were in fact killed. Government response also got harsher and several Luddites were hanged.

The climax of the Luddite Rebellion took place at midnight on Friday 28 June 1816. Sixteen men raided the factory of Heathcoat and Lacy at Loughborough, with around 1000 sympathisers cheering them on. They destroyed nearly all of the fifty-five lace-frames. Subsequently eight men were sentenced to death and two were transported.

The protests died down after that. Mechanization marched on, and the thousands who were involved in their traditional occupation lost out.

Technology will come. But how do we make the changes so we can reduce the negative impacts? How do we make the world a more inclusive place? Surely we cannot let history repeat itself!

–Meena

Photo-credit: historicalbritain.org/