Call them spineless, or call them creepy crawlies! As Meena wrote this week, they make up a majority of the living things on earth, and yet they are largely unnoticed (unless of course one is stung by one, or has one creeping up your leg!) Invertebrates however have had their own champions. One of whom is EO Wilson that Meena has quoted as saying that “invertebrates don’t need us, we need them!”

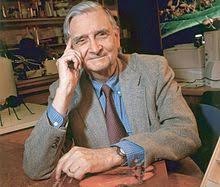

This was indeed the case with EO Wilson one of the most distinguished and recognized American scientists in modern history. While he began his scientific career by specializing in the study of ants, Dr Wilson became an advocate for all species, particularly invertebrates, as essential to the health of the planet and people.

While his key discovery was the chemical by which ants communicate, EO Wilson spent the rest of his life also looking at the bigger picture of life on Earth. And so, to his lifelong fascination with ants, E. O. Wilson added a second passion: guiding humanity toward a more sustainable existence. He devoted his life to studying the natural world, and inspiring others to care for it as he did.

Edward Osborne Wilson was not just the world’s foremost authority on the study of ants (a myrmecologist!) but one of the founding fathers of, and leading expert in, biodiversity. His autobiography titled Naturalist traces his evolution as a scientist. Young Wilson knew early that he wanted to be scientist. A childhood accident left him with weak eyesight and hearing, so instead of studying animals and birds in the field, he concentrated on the miniature creatures such as ants and bugs that he could study right under his nose through a microscope. This was the perfect tool to spark a lifelong passion for insects. I turned to the teeming small creatures that can be held between the thumb and forefinger: the little things that compose the foundation of our ecosystems, the little things, as I like to say, who run the world.

As a schoolboy Wilson was not a great reader. But he claimed that one of the few books that he read from cover to cover was The Boy Scout Handbook. (I wrote about this in my recent piece Be Prepared!) It was the Boy Scouts which nurtured his early love for nature. As he once said: The Boy Scouts of America gave me my education.

His autobiography Naturalist also reveals how these first steps led to a lifelong journey of exploration and discovery which involved a mix of endeavour, random encounter, enthusiasm and opportunism. Underpinning all these was his sheer delight of the pursuit of knowledge. As he wrote about an expedition to Fiji in 1954:

Never before or afterward in my life have I felt such a surge of high expectation—of pure exhilaration—as in those few minutes. I know now that it was an era in biology closing out, when a young scientist could travel to a distant part of the world and explore entirely on his own. No team of specialists accompanied me and none waited at my destination, whatever I decided that was to be. Which was exactly as I wished it. I carried no high technology instruments, only a hand lens, forceps, specimen vials, notebooks, quinine, sulfanilamide, youth, desire and unbounded hope.

Edward Osborne Wilson is widely considered one of the greatest natural scientists of our time. He is also credited for being the founding father of the branch of biology known as socio-biology and biodiversity. He was a pioneer in the efforts to preserve and protect the biodiversity of our planet and was instrumental in launching the Encyclopaedia of Life, a free online database documenting all 1.9 million species on Earth recognised by science.

In a tribute to his lifelong dedication to science, two species of organisms have been named after him. Myrmoderus ewolsoni, an antbird indigenous to Peru, and Miniopteru wilsoni, a long-fingered bat discovered in Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park. Wilson once told Scouting Magazine that being recognized in this way was an honour akin to being awarded a Nobel Prize because it’s such a rarity to have a true new species discovered.

EO Wilson was driven by the passion of guiding humanity toward a more sustainable existence. To do that, he knew he had to reach beyond the towers of academia and write for the public. He believed that one book would not suffice because learning requires repeated exposure. Thus he wrote several bestselling books that eloquently pleaded his case, while also providing facts and figures backed by solid research. His books On Human Nature and The Ants received the Pulitzer Prize.

While he remained a Harvard professor for 46 years, he was conferred with many accolades and honours by universities and organizations across the world. EO Wilson passed away on 26 December 2021 at the age of 92, leaving behind a legacy of conservation action that continues to inspire the global movement to end the threat of extinction.

In 2023, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) agreed to a Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) with a goal to maintain, enhance, and restore Earth’s natural ecosystems by 2030, halt human-induced extinction of known species, and by 2050, reduce the extinction rate tenfold and increase the abundance of native wild species to healthy and resilient levels. A key component to the GBF is a target to conserve at least 30 percent of land, seas, and freshwater by 2030 (known as “30×30”).

EO Wilson once wrote:

Looking at the totality of life, the Poet asks, who are Gaia’s children?

The Ecologist responds, they are the species. We must know the role each one plays in the whole order to manage Earth wisely.

The Systematist adds, then let’s get started. How many species exist? Where are they in the world? Who are their genetic kin?

EO Wilson was a rare combination of all three.

–Mamata