As we celebrate our 76th Independence Day, here is a look at a creature which is inextricably tied to the image of India—the elephant.

Though the tiger is our national animal, and lions stand proud on our national symbol, it is the elephant which is associated in popular imagination with India. Elepehants have traditionally been associated with the wealth, grandeur and ceremony of kingly India. Even today, people from foreign lands imagine elephants strolling the streets of the country.

A constant and less-than-flattering reference is to the Indian economy as an elephant. To quote former RBI Governor Dr. Duvvuri Subbarao, ‘In development economics parlance, the East Asian economies — Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong — are referred to as the tigers. The next generation of fast growing Asian economies — Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia — are referred to as the cubs. China is called the dragon. All these countries delivered a growth miracle in the last 40 years. ‘

‘India is referred to as an elephant because it is a strong animal with enormous potential but it moves at a lumbering pace. The hope is that it will start dancing and deliver the next growth miracle.’ (Knowledge at Wharton).

But coming back the elephant itself. Though elephants are so central to the imagination of India, ironically, one sees the image of the African elephant all around—from ads celebrating India and Indian products, to calendar art, to even textbooks and school charts.

The two are different at a very fundamental biological level. Asian elephants belong to the genus Elephas, species maximus, and African elephants to the genus Loxodonta, species africana. The two cannot interbreed and produce viable offspring.

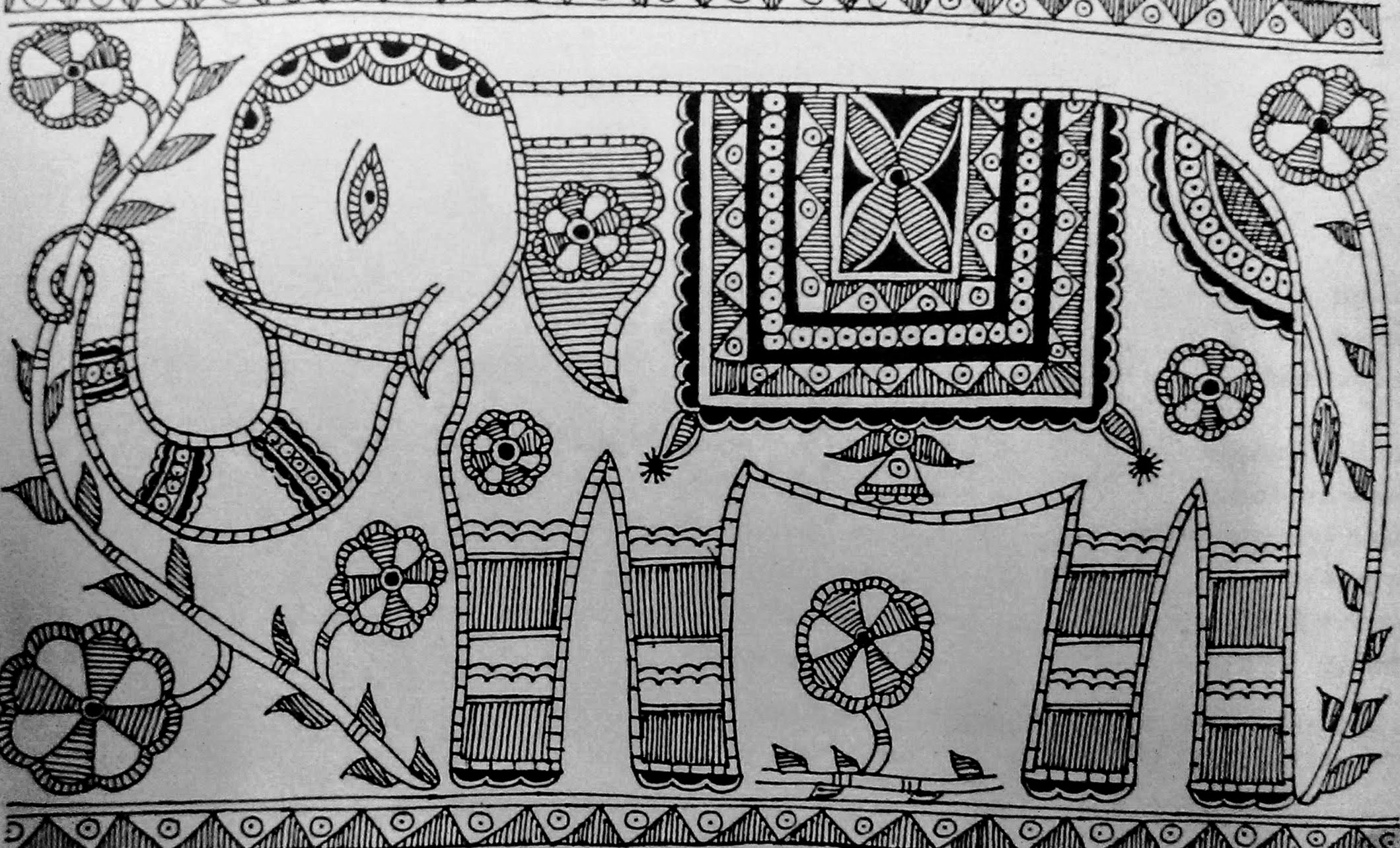

Physically, the African elephant is significantly taller and heavier than our Asian ones. Another obvious difference is that Asian elephants have small ears, while their African cousins have much larger ears, which cover their shoulders. All African elephants have tusks, while only male Asian elephants have tusks. (Artists seem to like depicting large ears and longs tusks on all the elephants they draw, which may be the reasons for the predominant image of African eles even in our media!). The trunk of the Asian elephant has one finger at the tip, while the African elephant has two fingers– this means that the way they pick up things is different—our elephants will curve their trunk around the object, while the African jumbo will hold the object between its two ‘fingers’, much as we would hold something between finger and thumb. Our elephants have two humps on the forehead, while African eles have one.

Importantly, Asian elephants are tameable, while African elephants are not. This is why in India, elephants have played such a large part in our lives—whether in religious ceremonies, in cultural processions, as royal symbols, as transport or war animals.

Thought still on the endangered list, conservation efforts seem to be paying off in India, with numbers reportedly on the rise, standing at about 28,000 this year, and elephant-bearing states vying with each other to report higher numbers. Project Elephant, launched in 1992, was critical in focussing attention on conservation of elephants and their habitats. Now, it has been merged with Project Tiger, based on the thinking that both animals inhabit the same habitats in some places. Only the future will tell if this is a good move, given that different issues confront the two majestic animals in different locations, and the move may take away the focussed attention on each of these.

On the economic front, bodies like the World Economic Forum think that ‘India’s economy is an elephant that is starting to run.’

As we wish our elephants to do well on World Elephant Day (August 12), we also hope, on Independence Day, that the Indian economy does well and all Indians attain a better quality of life.

Happy Independence Day!

–Meena