I recently, and reluctantly, bought a new pressure cooker, in place of my old one which has been my trusty companion over several decades and continents. The old one was an original English Prestige cooker, although over the years of replacement of its various parts (especially handles and gasket ring) with local add-ons made it a war veteran, scarred but not retired. Coincidentally, this week brought the news of the demise of TT Jagannathan who made TTK and Prestige a well-known and trusted Indian brand. In fact the Prestige pressure cooker is such a ubiquitous presence in every home, that we take complete ownership of its being uniquely Indian.

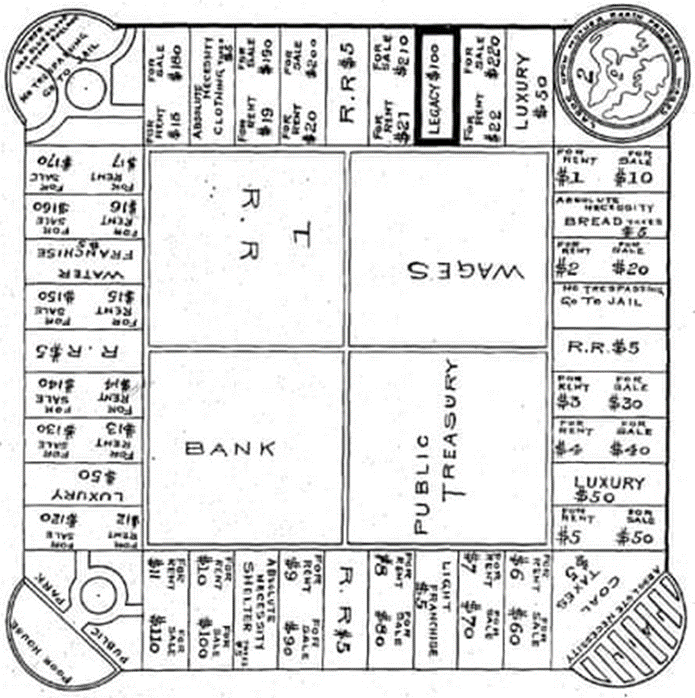

In fact the origin of a utensil that could cook food at high temperature can be traced back to the 17th century in England. Its earliest form was called a Digester. It was devised by Denis Papin, a French physicist, mathematician and inventor, who had moved to England. The Digester was a large cylindrical airtight container, heated over coals to produce internal steam pressure to increase the boiling temperature to above 100 degrees centigrade. A small tube in the lid closed with a flap was held in place by a weighted rod allowing the steam to escape when the pressure became too high. This was an early version of the first safety valve, one that helped prevent the contraption from exploding. In 1679, Papin presented his invention to the Royal Society which included top scientists of the day. They were so impressed that they commissioned Papin to write a book. The book published in 1681 titled A New Digester or Engine for Softening Bones detailed his successful experiments in cooking a variety of meats and was described as a construction guide, an experiment log, and a cookbook. In 1682, Papin used his Digester to cook a full meal for the Royal Society dinner which received rave reviews. However the Digester as a cooking equipment did not really take off in England till much later. Papin moved on to Germany and continued his experiments leading to other inventions based on a similar application of the pressure of steam.

The early Digester was expensive to build and could be rather dangerous as there was the threat of explosion from too much steam pressure. It wasn’t until the addition of safety valves that effectively stopped the pressure from getting too high, and safety locks preventing the lid from flying off if opened too soon, would such a utensil become more common. Papin died in obscurity, not knowing that his Digester would one day transform into the domestic pressure cooker.

But the technology triggered other experimenters to work on similar devices. In 1919, José Alix Martínez was granted the first patent in Spain for his olla exprés (express cooking pot), which used the pressure cooker technology invented by Papin. However, the term “pressure cooker” featured in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1910. In simple terms, a pressure cooker is a sealed chamber that traps the steam generated when its contents are heated. As the steam builds up, pressure increases and drives the boiling point of water beyond 100°C. Pressure cooking reduces cooking time up to 70per cent, preserves more nutrients and vitamins, uses less energy and water, and can be used to cook a wide range of foods

Around the same time, a new invention appeared in India which used steam, though not steam pressure, to cook food. This was the creation of a Calcutta gentleman Indhumadhab Mallik. In this, raw ingredients including meat and fish as well as vegetables dal and rice were placed in containers which were stacked in an inner container. The outer container had water, and the entire contraption was sealed and placed over a charcoal fire. The food cooked in the steam that was generated. The steam cooker was called ICMIC cooker (combining the words hygienic and economic.) The cooker became popular in Bengal and was also sold in other states under different names.

By the 1930s, the pressure cooker was making its presence felt across the world, even as high up as Mount Everest. Higher altitudes with lower atmospheric pressure meant longer cooking time and a pressure cooker helped ease the problem, making it a great help in mountaineering expeditions.

World War II led to a dip in the production of pressure cookers due to the need for aluminium for the war effort in the US and Europe. Pressure cooker companies were enlisted to create canned goods (the cans were made of aluminium) for the troops. However, there was continuing demand for pressure cookers, and some companies started making cheaper cookers with substandard materials, which caused the cookers to explode. This raised safety concerns leading to the fall in popularity of pressure cookers in Europe.

Pressure cookers arrived in India in the late-1950s. They were introduced by two companies—Hawkins and TTK Private Ltd. (which became known as TTK Prestige). But the safety issue remained a concern as there were frequent explosions. Simultaneously companies were working on innovations to prevent such mishaps.

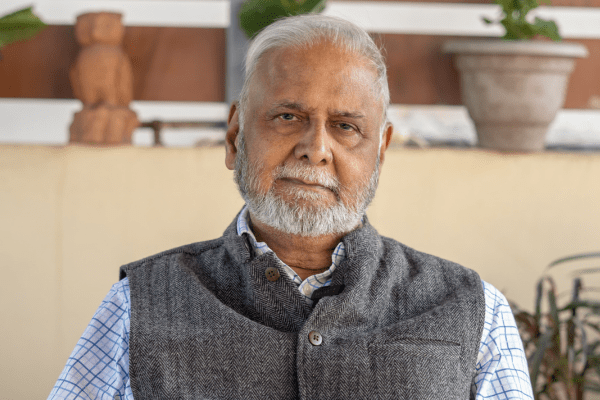

A significant contribution in this field came from TT Jagannathan (TTJ) who joined the family business when he was in his early 20s, and took charge of TTK Prestige at a time when the company was struggling. The reports of faulty pressure cookers had severely damaged the company’s reputation. Jagannathan, an engineer from IIT Madras and a PhD in Operations Research from Cornell began experimenting with ways to increase safety in pressure cookers.

As he recounted in his book Disrupt and Conquer: How TTK Prestige Became A Billion-Dollar Company, Mr Jagannathan saw a godown full of unsold pressure cookers on a visit to Lucknow. The dealer explained that there were increasing cases of TTK pressure cookers bursting, and that the TTK name had lost credibility. TTJ was disturbed and launched a probe into the reason for this. A pressure cooker comes with a weight valve that is meant to rise up and release the steam that is built up by the pressure inside the cooker. The valve then settles back in place. The safety plug is a back-up safety mechanism and regulates the pressure built up in the cooker if the weight valve fails. He discovered that users were unknowingly purchasing fake safety plugs to replace the original ones. These plugs were cheaper but also made of substandard material which allowed too much steam build-up, leading to exploding cookers. He realized that there needed to be a device which, even when poor materials were used, could prevent this from happening. He immediately contacted his company’s head engineer and asked him to make certain preparations. TTJ returned to Bangalore and spent a month in the lab and used his engineering knowledge to create just such a device. This was the Gasket Release System or GRS. GRS is a secondary safety feature that releases excess steam if the primary pressure valve fails, preventing a dangerous pressure build up. It works by providing a weak point in the lid where a section of the rubber gasket will be pushed out through a slot if the main pressure vent becomes blocked or fails, allowing steam to escape down and away from the user.

This safety feature set new standards across the industry, and was also adopted by other manufacturers of pressure cookers in India. Its inventor TTJ never patented it. As he said “I did it for the industry. If any pressure cooker burst, it would mean a loss for the category. The category wouldn’t grow if people had fears around safety. I didn’t want only Prestige to be safe, but all pressure cookers in the country to be safe.”

The invention, along with Prestige’s close and continuous outreach and contact with its customers has ensured that the brand is associated with quality, durability and reliability. Today the Prestige brand has introduced a wide range of kitchen appliances catering to a new generation and befitting the ‘smart kitchens’. However the name’s first association is so much with Pressure cookers that Prestige is synonymous with Pressure cooker.

–Mamata