And all I could see was fire and smoke! Everything outside seemed to be burning. I could hear cries of ‘Allah ho akbar’ and ‘Hey Ram’. There was not a soul on the platform. We and the other newly married couple from our bogey got down. We didn’t know what to do—we just stood there for a few minutes, with all our luggage. I was holding the ‘chumbu’ that had not fitted into any trunk. My veena, wrapped in old sarees, lay at my feet. I had no clue what was going on. My husband looked worried, but I did not know what he was worried about. We had thought that athimber (my husband’s sister’s husband) would come to the station to take us home. We had heard that there was some trouble in Delhi, and thought that surely he would have arranged for transport. But there was no one there.

Then a porter appeared. He came to my husband and they started speaking in Hindi. I could only understand a few words of Hindi at that time, so I don’t know what they said.

After a lot of discussion, the porter hurried away and returned with a cart of some kind. We loaded all our luggage onto this. But the veena would not fit in—the neck stuck out. So my husband picked it up. I was still carrying the chumbu.

My husband only said ‘Walk fast. Don’t make a noise’.

I could not understand where we were going. We got down from the sloping end of the platform and crossed some tracks and kept walking along the tracks. They were going so fast, I was finding it difficult. I was hungry—the GT was supposed to have reached at 5 o’clock in the morning, but it had reached at 5 o’clock in the evening.

As we walked along, there were houses on the sides. They all looked the same. It was some colony. We saw not a soul on the way. I could not make out whether anyone lived in the colony or they were all empty houses.

It was difficult to manage all the luggage in the cart as we walked over the uneven ground. There were trunks with clothes. Two holdalls. My mother had tied up vessels and kitchen items in old sarees. Then there were tins with different types of sweets and savories. My father had bought a blue glass jar from his lab supplier because I loved them. My mother had filled it with mixture ordered from the hostel. She told me I could use the bottle later to store something in the kitchen. Suddenly the blue jar fell down and broke. Tears came to my eyes, but I did not dare cry. We just kept walking on.

After about half an hour of walking, the porter stopped the cart near one of the houses. He went to the door and knocked softly. Someone looked out of the window. On seeing the porter, he came to the door and opened it slightly. He was dressed like a watchman.

They whispered to each other. Then the porter signaled to us to take the luggage into the house. The house was full of piles of luggage. The watchman shifted a few pieces here and there and made some space for our luggage. We brought in the pieces one by one and put them there.

I asked my husband in Tamil: ‘Are we going to leave the luggage here? All the silver vessels are here. How can we leave them?’ My heart was sinking. My mother had bought two large oval plates and two tumblers specially for my coming to my husband’s house for the first time.

He just hissed at me to keep quiet. He took the porter and watchman to a corner, said something to them and gave them lot of money. We walked out. The veena was in my husband’s hands—it was too big and odd shaped—we could not put it in the room. And for some reason, I was still carrying the chumbu.

When we had walked a few minutes, I saw a huge railway water spout gushing water. I ran to it. Only when I started drinking did I realize how hungry and thirsty I was. I drank and drank. Then we walked on. We had now left behind the colony and were in the city. My husband told me there was a curfew on but it was relaxed for an hour and so we had to hurry and reach home. But I didn’t know what a curfew was. We walked quietly along the side of the lanes.

And then the horror! A man came running from one direction. There was another man chasing him. He caught up with him, and in front of our eyes, he drove a knife into the first man. Blood spurted out. I was going to scream, but my husband clamped his hand on my mouth. The killer pulled the body and threw it into the gutter on the side of the road and ran away. He had not noticed us.

I asked my husband why that man had killed the other one, what was happening? But he just gestured to me to keep quiet and walked on.

By the time we reached home, it was dark. It was not our house, my husband told me. ‘This is Tagore Road. My sister’s house. Our house is in Lodhi Road—too far away.’

We went in. Our brother-in-law was there and 2 other families who were sheltering there because their own areas were not safe. My sister-in-law and mother-in-law had gone to our house in Lodhi Road to get the house ready for us, but had got stuck there.

The ladies welcomed us and did aarti. One of them said ‘Are you hungry? There is some arisi upma we made in the morning. You can have that’. Never had food tasted so good. But there was not much. Even as we were eating this, the ladies started cooking dinner. There was a murungakka tree in the garden. So they made murungakka sambhar and rice. This was the menu for the next three days, both for lunch and for dinner.

In the night, all the ladies slept in one room. We each would keep a cloth with red chili powder in it, and a heavy stone (ammi) or something like that next to our pillows. The ladies told me that if anyone should come into the house, I should throw the chili powder in their eyes. The men would go out in groups and do rounds of the colony. They had piled up stones and reapers across the lane entrance.

I was fifteen years old at that time. The year was 1947.

–Meena

This is the true story of the day my athai (father’s sister) landed in Delhi as a new bride, in the midst of the Partition.

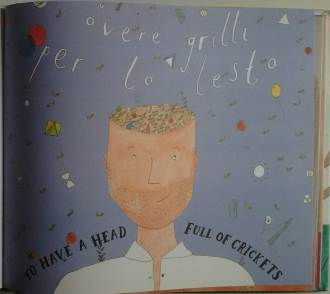

From Finnish to Igbo, Armenian to Yiddish, each double spread presents delectable sayings and drawings that blend the wit and wisdom of the ages while also placing these in their cultural context.

From Finnish to Igbo, Armenian to Yiddish, each double spread presents delectable sayings and drawings that blend the wit and wisdom of the ages while also placing these in their cultural context.