Every writer knows well the sudden point in the flow of words where you struggle to find another/better/appropriate word. And where a dictionary will not serve the purpose. That is the time to turn to the trusted Thesaurus with its rich listing of synonyms.

The word thesaurus itself came to the English language in the late 16th century, via Latin, from the Greek word thēsauros meaning ‘storehouse or treasure’. It was used in the early 19th century by archaeologists to denote an ancient treasury, such as that of a temple. Soon after that, the word was metaphorically used to describe a book containing a “treasury” of words or information about a particular field.

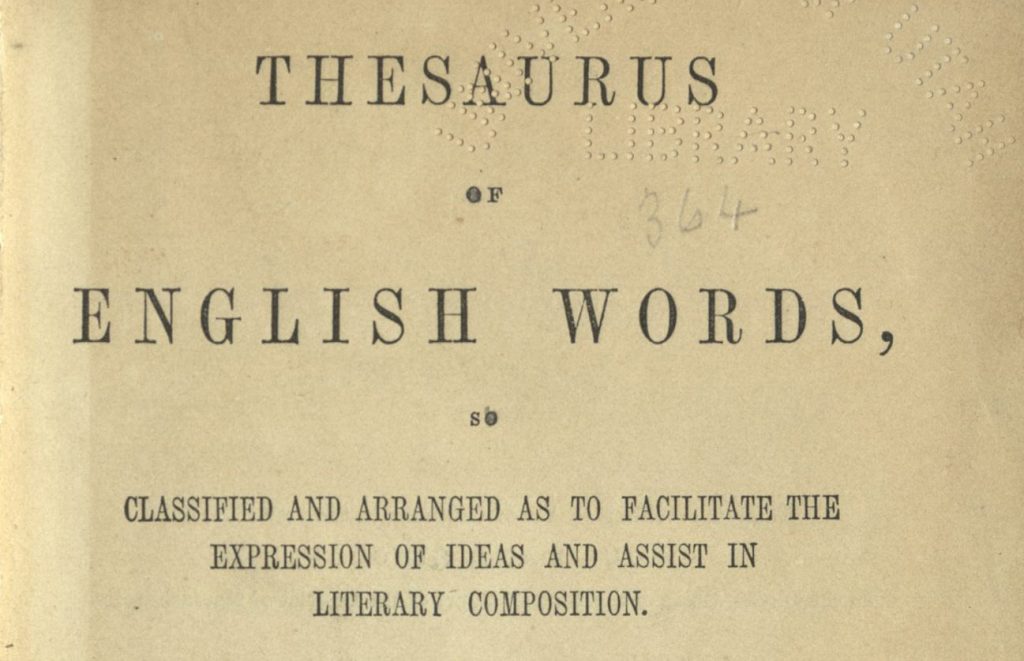

In 1852, the English scholar Peter Mark Roget published a book in which he compiled lists of related words which were organised according to specific categories. The book was titled Thesaurus of English Words, Classified and Arranged as to Facilitate the Expression of Ideas and Assist in Literary Composition. This led to the common acceptance of the term “thesaurus” to describe a book of words and their synonyms. In the years to come the word Roget itself became a synonym for Thesaurus.

One would have imagined that the Thesaurus was the magnum opus of its author Peter Roget who spent his life as a wordsmith. In fact, Roget was a multi-faceted individual who wore many hats in his lifetime.

Peter Mark Roget was born on 18 January 1779 in London. His father was a clergyman of Swiss origin, and his mother was the sister of a notable law reformer Sir Samuel Romilly. After the death of his father when Peter was only four years old, the family moved to Edinburgh. The young Peter was a brilliant student, graduating from medical school in Edinburgh at the age of 19. His ardent curiosity led him to research and experiment in numerous fields of knowledge. As a young doctor he published works on tuberculosis, and on the effects of nitrous oxide, known as ‘laughing gas’, then used as an anaesthetic. He then moved on to Bristol and Manchester where he worked as a private physician and also as a tutor.

In 1808 he moved to London, where he continued to pursue his diverse interests in medicine and science. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society, Britain’s national academy of science, and served as its secretary for 21 years. The government asked him to explore London’s water system. He sought to improve sanitation and food preservation, even discussing the concept of a ‘frigidarium’. He helped to found Manchester Medical School and the University of London. He wrote numerous entries for various encyclopaedias. He invented a pocket chessboard, and a new type of slide rule. He was also interested in optics and wrote a paper on how the kaleidoscope could be improved.

While his professional life was marked by prodigious achievements, Peter Roget’s personal life was traumatic and tragic. He hardly knew his father who died when he was very young; his mother suffered from paranoia, and his sister experienced mental breakdowns. His wife died of cancer when she was only 36. And Sir Samuel, his favourite uncle and surrogate father slit his own throat, even as Roget tried to pull the blade from his hand.

Roget himself was afflicted with depression, and developed such a repugnance of dirt and disorder, that would today be diagnosed as OCD. Perhaps as a reaction to all this turmoil, he also became obsessed with numbers and lists. The obsession also worked as therapy.

From the time that he was a young boy, Peter made lists. The process of sorting and classifying provided a sense of order and logic. As early as 1805 when he was 26 years old, he had compiled, for his own personal use, a small indexed catalogue of words which he used to help his prolific writing. He continued with this exercise of classifying and cataloguing words even as he continued his distinguished career in medicine and science.

It is only when he retired from medical practice age the age of 60 that Roget devoted all his time and energy on the project that would, in later years, eclipse all his former achievements. For four years he worked on the task of arranging ideas, meanings and concepts. The contents were not arranged alphabetically but put in an order where a given idea fitted into his own classification, within six classes: Abstract Relations, Space, Matter, Intellect, Volition, and Affections.

Whereas a conventional dictionary starts with words and provides their meanings, pronunciations, and etymology, Roget’s Thesaurus was the converse, namely, an idea was given alongside the word or words by which that idea could most aptly be expressed. Although philosophically orientated, the Thesaurus was a compendium of thematically arranged concepts, a classification of words by their meaning.

Roget’s Thesaurus was finally published in 1853, when Peter Roget was 74 years old. It had a print run of 1,000 copies. The 15,000 words it contained were arranged conceptually rather than alphabetically, incorporating 1002 concepts. But shortly before publication, he inserted an alphabetical index as an appendix, thus enabling its easier use.

The first American edition of the Thesaurus was published in 1854. In the introduction to this, Roget explained: “The present work is intended to supply, with respect to the English language, a desideratum hitherto unsupplied in any language; namely, a collection of the words it contains and of the idiomatic combinations peculiar to it, arranged, not in alphabetical order as they are in a dictionary, but according to the ideas which they express.” The Thesaurus initially did not do as well in America. It only became popular in the 1920s when the crossword craze swept the United States.

Roget continued to make changes until his death at the age of ninety, by which time there had been twenty-eight editions. His son, John Lewis Roget continued its revision. Roget’s Thesaurus has never been out of print and by its 150th anniversary in 2002 had sold thirty-two million copies. From his original six classes, by the time of the eighth edition in 2019 it included 1,075 word categories.

Today while the word Roget immediately brings to mind the word Thesaurus, its author’s illustrious career in medicine and science is not as well known. His birthday week is a good time to remember the many other words to describe Peter Roget: Physician, physiology expert, mathematician, inventor, investigator, writer, editor and chess whiz.

–Mamata