Welcoming the new year with the ringing of bells is an old tradition, immortalized by the lines from the familiar lines by Alfred Lord Tennyson.

‘Ring out the old, ring in the new,

Ring, happy bells, across the snow;

The year is going, let him go;

Ring out the false, ring in the true.’

Down the ages and across the world, bells have played an important role—from summoning people to a gathering place, to a role in religious rituals, to announcing danger, to attracting attention. And importantly, to summon children to school, and provide them joyful reprieve at the end of classes! I am talking of course of traditional metal bells which are rung manually. These traditional bells are ‘melodic percussive musical instruments usually made of metal (bronze, copper, or tin) but sometimes made of glass, wood, clay, or horn. When a bell is struck by a clapper (an interior object) or an exterior mallet or hammer, the bell, constructed of solid, resonant material, vibrates and produces a sonorous ringing sound’. Each bell is unique, depending on the material it is made of, how thick it is and its size and shape. Based on these factors, it resonates at certain harmonic frequencies and pitches.

A bell is usually suspended from a yoke– a cross piece that allows the bell to hang freely. The top of the bell is known as the crown and the middle portion is called the waist. The lower open section is known as the mouth, and the lower edge of the bell is called a lip. The part of the bell which is struck with a clapper is the thickest part of it, and is called the sound bow. Some bells are rung with clappers, a metal sphere that swings inside the bell Others are struck with a mallet or stick externally.

Gungroos represent a variation. Rather than being bell-shaped, they are orbs, with a few openings, which have small metal balls or even tiny stones enclosed within, which rattle and produce a tinkling sound.

With new technologies and means of communications, traditional bells and the traditional role of bells is diminishing. But interest in these bells and bell-ringing is alive. Many thousands of people around the world practice bell-ringing as hobby!

In fact, January 1 is observed as Bell Ringing in some countries. Many universities in the UK have bell-ringing clubs. When you join such a club, you first have to master the technique of pulling the rope attached to the clapper in a rhythmic way. Once you have mastered this, you can start “change ringing”–rhythmically ringing in a descending scale and then changing the order in which the bells ring in various different ways. Team bell-ringing is an activity which requires immense amount of coordination, and is a competitive event!

Bell Ringing Day not only sets out to encourage bell-ringers, but also to focus attention on the need to restore and maintain bells.

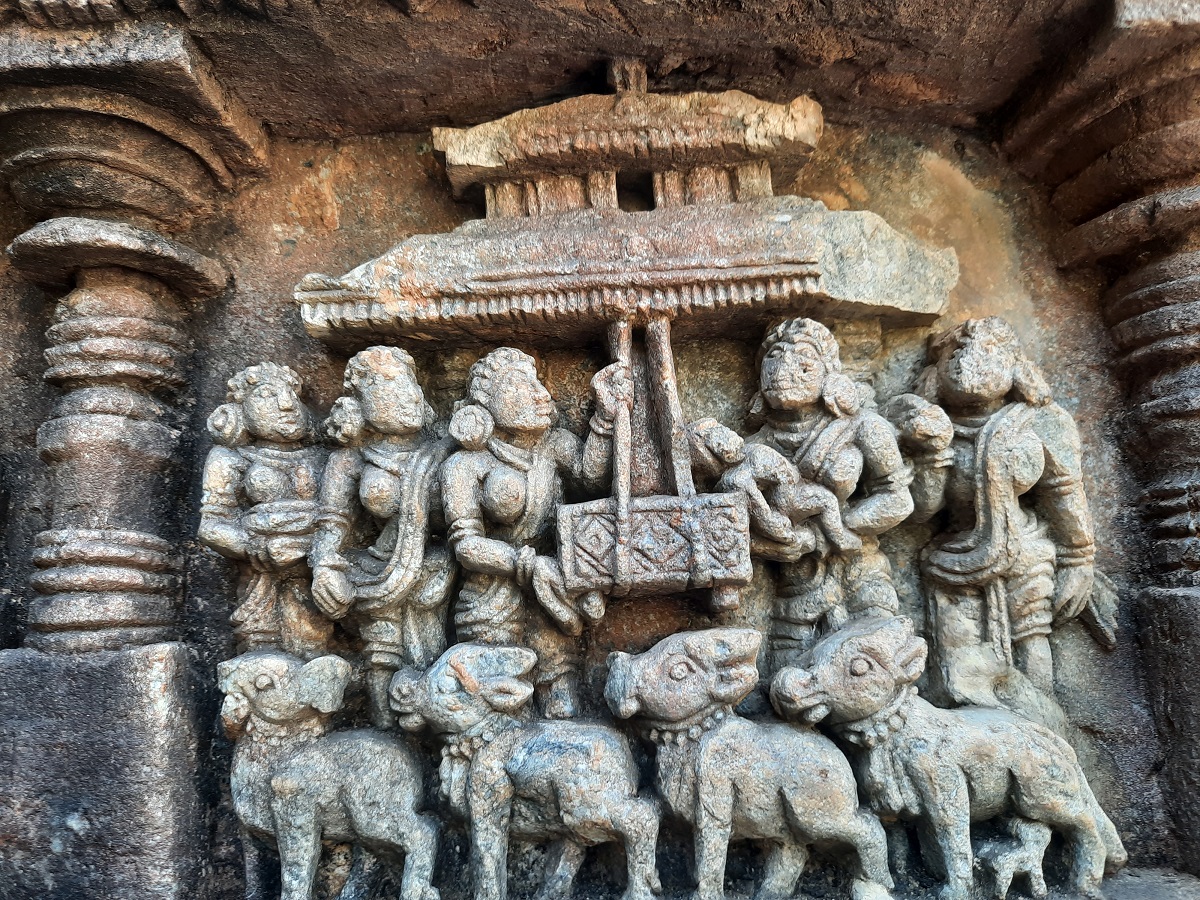

Our temples have beautiful bells which devotees ring as they go in. Most homes have small bells, and pujas are accompanied by the chiming of bells. Dancers wear ghungroos or rows of bells on their ankles. Cows are adorned with bells which chime as they move.

A cheery note to begin the year!

Happy New Year, and may the chiming of bells bring in good tidings!

Peace on earth, and goodwill to all.

–Meena