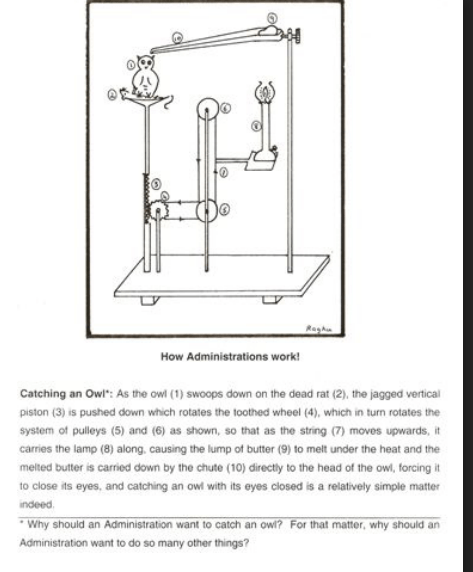

If there is a monument to human overthinking, it has to be the Rube Goldberg machine.

Named after the American cartoonist Rube Goldberg, these contraptions perform the simplest of tasks—turning on a light, pouring a glass of water, popping a balloon—in the most complicated way possible. A marble rolls down a ramp, tips a spoon, flicks a switch, releases a toy car, which hits a domino, which startles a rubber duck… and several improbable steps later, the job is done. Eventually.

At first glance, Rube Goldberg machines seem like elaborate jokes. In fact, they began as precisely that. In the early 20th century, Goldberg drew cartoons of absurdly complex inventions that parodied America’s growing obsession with technology and efficiency. His most famous series, “Inventions,” featured machines with labels like “Self-Operating Napkin” or “Simple Way to Take Your Own Picture.” The humour lay in contrast: why build a 20-step mechanical circus to do what your hand can accomplish in two seconds?

Yet over time, the joke evolved into a genre.

At their heart, these machines are celebrations of cause and effect.

Each step must trigger the next with precise timing. A falling object transfers energy. A lever multiplies force. A pulley redirects motion. Though they look chaotic, good Rube Goldberg machines are carefully engineered systems. Behind the apparent madness lies an understanding of physics—gravity, friction, momentum, torque.

That’s why they are so beloved in STEM education. Today, Rube Goldberg machines are built in classrooms, engineering labs, art studios, and living rooms. There are national competitions in the United States run by the Rube Goldberg Institute, where students design multi-step chain-reaction machines to complete assigned tasks. The goal is not efficiency but creativity, reliability, and storytelling through mechanics. Building one requires planning, testing, recalibrating, and accepting failure—lots of it. If step 17 misfires, the entire sequence collapses. Students learn quickly that systems thinking matters. Every action has consequences, and tiny misalignments compound.

(From V. Raghunathan’s series ‘How Administrations Work!’ featured in the Financial Express. A satire on administration, based on Goldberg machines).

And yet, beyond physics, Rube Goldberg machines are deeply artistic.

Watching one in motion feels like choreography. There is suspense as the marble pauses on a narrow ledge. There is surprise when a balloon bursts. There is delight when the final flag pops up to declare success.

Modern technology hides complexity behind smooth interfaces. Tap a screen and food appears. Click a button and money transfers. Rube Goldberg machines do the opposite—they expose process. They revel in visible mechanisms, in levers and ramps and strings that refuse to disappear into abstraction.

Perhaps that is why they continue to fascinate adults as much as children.

Unlike automated factories or digital code, these machines often fail in spectacular fashion. A domino tilts the wrong way. A ramp shifts. A candle burns too slowly. The collapse is not embarrassing—it is part of the show. Viewers laugh, builders reset, and the experiment continues.

In this way, Rube Goldberg machines mirror creative life itself. Progress rarely moves in straight lines. We improvise. We overcomplicate. We learn through misfires.

As a STEM tool perhaps most importantly, it fosters curiosity.

Why does the marble move faster on a steeper incline? What surface reduces friction? How much force is needed to tip the spoon? Questions arise naturally when objects misbehave. The machine becomes a laboratory disguised as a toy.

More than a century after Rube Goldberg first skewered modern gadgetry, his name has become synonymous not with satire but with ingenuity. What began as mockery of unnecessary complexity has turned into a celebration of imaginative problem-solving.

Today, there are national competitions in the United States run by the Rube Goldberg Institute, where teams design multi-step chain-reaction machines to complete assigned tasks. The goal is not efficiency but creativity, reliability, and storytelling through mechanics.

Beyond competitions, the aesthetic has spilled into popular culture and design.

In 2003, Honda released its now-iconic “Cog” commercial featuring parts of a Honda Accord arranged in a flawless chain reaction. Gears tipped into springs, springs released bearings, bearings rolled into levers—culminating in the car moving forward. No computer graphics. Just painstaking mechanical precision.

Similarly, the band OK Go transformed chain reactions into performance art in their video “This Too Shall Pass,” filling a warehouse with cascading objects, swinging pendulums, and erupting paint cannons. The machine became choreography. Cause and effect became spectacle.

Kinetic artist Joseph Herscher constructs domestic Rube Goldberg devices that wake him up, butter his toast, or serve tea through absurd sequences of ramps and levers.

And then there are works that stretch the idea into art philosophy. Dutch sculptor Theo Jansen builds wind-powered walking structures known as Strandbeest—intricate skeletal forms that move across beaches through elaborate mechanical linkages.

More than a century after Goldberg first thought these up, his name has become synonymous not just with unnecessary complexity, but with imaginative possibility. What began as satire is now a tribute—to curiosity, to process, and to the delicate chain reactions that connect one moment to the next.

–Meena