This month we had a family get together bringing together members from different parts of the world, as well as different generations. It was also an occasion to celebrate together, several birthdays of the gathered family members—from the first birthday to the seventieth birthday. Topping up all the celebrations including cake-cutting and candle blowing, was a lusty rendering of the song Happy Birthday to You.

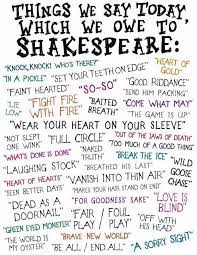

It is quite incredible how this song has transcended time and space to become a universal symbol of birthday celebrations. It is said to be the most frequently-sung English song in the world. And it is sung quite comfortably by people who may otherwise not know any other word of English. What most people do not know is that this song has an interesting history which dates back over a hundred years.

The creators were Patty and Mildred Hill, two sisters who were kindergarten teachers in Louisville, Kentucky, USA. Patty was not just a teacher, she was one of the pioneers who introduced what was then, a progressive philosophy of early childhood education in America. She stressed that in the early years supporting creativity, and social and emotional development of children were as important as academic learning. This could be provided by good kindergartens. The Hill sisters themselves grew up in a progressive family which supported and encouraged the daughters to have a complete education and have a career—both unconventional approaches for that period. Their parents believed that children should be free to play and follow their own pursuits as well as learn the value of hard work. Growing up in such a home had a profound influence on Patty whose future career choice would manifest her beliefs on the kind of education every child deserved. She had a strong commitment to and the importance of self-determination in activity, especially in childhood, as a means of empowering individuals to overcome social and economic disadvantages.

Patty Hill graduated from Louisville Collegiate Institute in 1887 after which she joined the Louisville Kindergarten Training School where the students were encouraged to experiment with different classroom techniques. Patty Hill began her kindergarten work as a teacher, and then became director of the Louisville Free Kindergarten Association in Kentucky in 1893. During her time at the Louisville Kindergarten Training Schools, Hill was very active in the Kindergarten Movement. She participated in numerous conferences and organized events that discussed alternative methods of early childhood education. She developed curricula that encouraged children to learn through play, music, free play, and contact with nature. The Louisville Kindergarten Training Schools became famous in the United States as the centre of innovative ideas about early childhood education. In 1906 Patty was appointed to the faculty of Columbia University Teachers College, where she taught for the next 30 years. There she developed a curriculum that emphasized the importance of a child’s first-hand contact with nature for creative expression. In 1908 she was elected president of the International Kindergarten Union. In 1924 Patty helped to found the Institute of Child Welfare Research at Columbia and also promoted the extension of nursery schools through her work with the National Association for Nursery Education, which she helped to organize in 1925.

Patty Hill served on the faculty of Teachers College at Columbia University until she retired in 1935. After her retirement she continued to give lectures and public speeches until her death in 1946 in New York City.

Despite her significant contribution to early childhood education, Patty’s claim to fame however lies more in her links with the Happy Birthday Song. In early 1893, when she was at Louisville Kindergarten Training Schools, Patty and her sister Mildred, who was a pianist and performer, composed a simple 4-line song for the kindergarten students which had “words and emotions and ideas” that they felt were suitable for the limited musical ability of a young child. Patti wrote the words and Mildred composed the score. It had only six notes, six words, and four lines, three of them the same. They would work at night on the tune, and the next morning try out the song in the classroom. The lyrics were simple: “Good morning to you / Good morning to you / Good morning, dear children / Good morning to all.” The tune had a simple, repetitive beat, and was easy for children to follow. They tested the song with their young students until they found a combination that children caught onto easily, as they enjoyed the words as well as the rhythm.

The sisters published Good Morning in 1893 in a book of sheet music called Song Stories for Children, which they copyrighted and exhibited that year at the World’s Fair in Chicago.

How did the words ‘Good Morning’ transform into Happy Birthday, even as the tune remained the same? There are many theories, of which one is that the sisters themselves changed the words at a birthday party that they attended. In fact, the tune was amenable to easy exchange of words, and children at the Louisville Experimental Kindergarten School where Patty taught would substitute the words with Goodbye to You, Happy Vacation to You, and other variations.

By 1924, the song appeared in another songbook edited by Robert Coleman with the Hill sisters’ original lyrics as the first verse, and “Happy Birthday to You” as the second. As the song started to appear more in print, it caught on like wildfire and became hugely popular from coast-to-coast. It began to be used in movies and Broadway musicals. Ironically the sisters never published or copyrighted the lyrics to Happy Birthday to You.

There followed a long and complex battle of claims for copyright and licencing of the song. None of the legal battles produced a conclusive verdict on the song’s authorship or ownership. In the 1930s, the Hill sisters won the copyright for the song as it appeared in a songbook for children published by The Summy Co. But in 1988 Warner Communications acquired the rights to the tune. This meant that anyone who wanted to use the song in a movie or TV show would have to pay thousands of dollars. To avoid the high royalty fees, many movies and TV shows figured out creative ways to portray birthday celebration scenes without actually using the ‘Happy Birthday’ song. Despite this, at one time, Warner/Chappell Music was earning as much as $2 million per year in licensing fees from the birthday song.

In 2016, a group of artists and filmmakers filed a lawsuit which challenged Warner’s claim to the copyright of the happy birthday song, and claimed that they should not be allowed to charge licensing fees for use of the musical work. Warner Music Group lost the case, and as part of the class settlement, the company had to pay $14 million to people and organizations that had paid royalties to use “Happy Birthday” since 1949.

As of 2016, the famous Happy Birthday Song is in the public domain, meaning that it can be sung anywhere. The next time we sing Happy Birthday to You to celebrate a birthday, let’s also celebrate its interesting roots and long history.

–Mamata