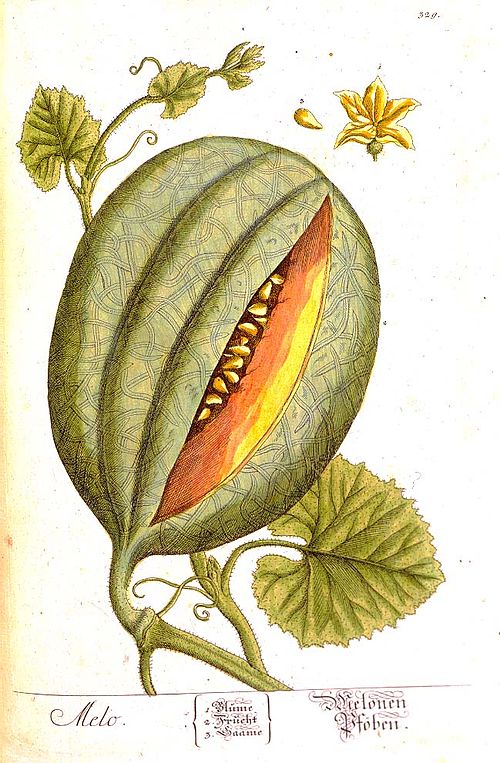

It is Moon Week! Meena wrote about the different facets of the moon, in fact and fantasy. Just a couple of days ago, the Axiom 4 mission returned from its space sojourn with Grp. Captain Shubhanshu Shukla being a proud Indian member of the team. Much has been in the news about the experiments that the team carried out while on the International Space Station (ISS). One of these experiments was to sprout methi and moong seeds in petri dishes and then storing these sprouts in a storage freezer on the ISS. This experiment was part of the Sprouts project, designed to study how spaceflight affects food germination and plant development. Insights from this project could transform space agriculture to enable it to support a reliable supply of food for future space travelers. Some of the seeds will also be brought back to earth, and cultivated over several generations while research is carried out on the genetic, microbial and nutritional changes in these space-returned seeds. Today, astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) regularly eat salad grown on board. Future long-duration exploration of the Moon and Mars depends on being able to grow fresh food in deep space.

Seeds have been travelling to space since 1971 when the Apollo 14 mission was launched. The mission put two astronauts Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell on the moon. As they walked on the moon the third astronaut Stuart Roosa continued to orbit above in the command module. Stuart Roosa was a former US Forest Service smoke jumper (a fire-fighter who parachutes to the site of a forest fire), before becoming a military aviator and astronaut.

When Roosa was selected for the moon mission he was entrusted with another important mission—to carry hundreds of seeds of trees with him. This was part of a joint experiment of NASA and the US Forest Service which selected seeds from five different types of trees. The seeds were x-rayed, sorted and classified, and sealed in small plastic bags stored in a metal canister. Roosa, the official ‘seed ambassador’ for the project carried the canister with more than 2000 seeds in a small canvas pouch as part of his personal belongings. This was the first time that seeds were being sent into deep space and it was an experiment to study how this would affect the seeds’ health, viability and long-term genetics. The seeds under Roosa’s care successfully completed the mission to the moon, but following their return the seed bags burst open during the decontamination process, leading to fears that the experiment’s environment had been contaminated and the seeds would not be viable. Nevertheless they were sent to the Forest Service offices in several places to see if they would germinate. In fact, many did germinate and grew into viable saplings. These 450 saplings were gifted to schools, universities, parks and government offices across the United States, in suitable locations in terms of climate and soil.

The saplings grew into trees which came to be known as ‘Moon Trees’. These were planted alongside their Earth-bound counterparts in order to compare the two. Fifty years later both grew into mature trees with no discernable difference.

Subsequently the collaboration between NASA and US Forest Service has continued with more seeds traveling to space with different missions. Upon their return the space seeds have been planted, and the next generation of Moon Trees are taking root and growing in multiple places. While the seeds in space have contributed to science, the Moon Trees are playing an important role in sparking curiosity about space, fostering a deeper understanding of NASA’s missions among the new generations of students, and nurturing community connections where they thrive.

Today there is a Moon Tree Foundation which aspires to unite, inspire, and conserve by planting a Moon Tree in every corner of the world. Its mission is to inspire interest in education, science, space, conservation and peace for all mankind. Moon trees serve as a reminder to take care of our planet for future generations as “we are under the same sky, looking at the same moon.”

–Mamata