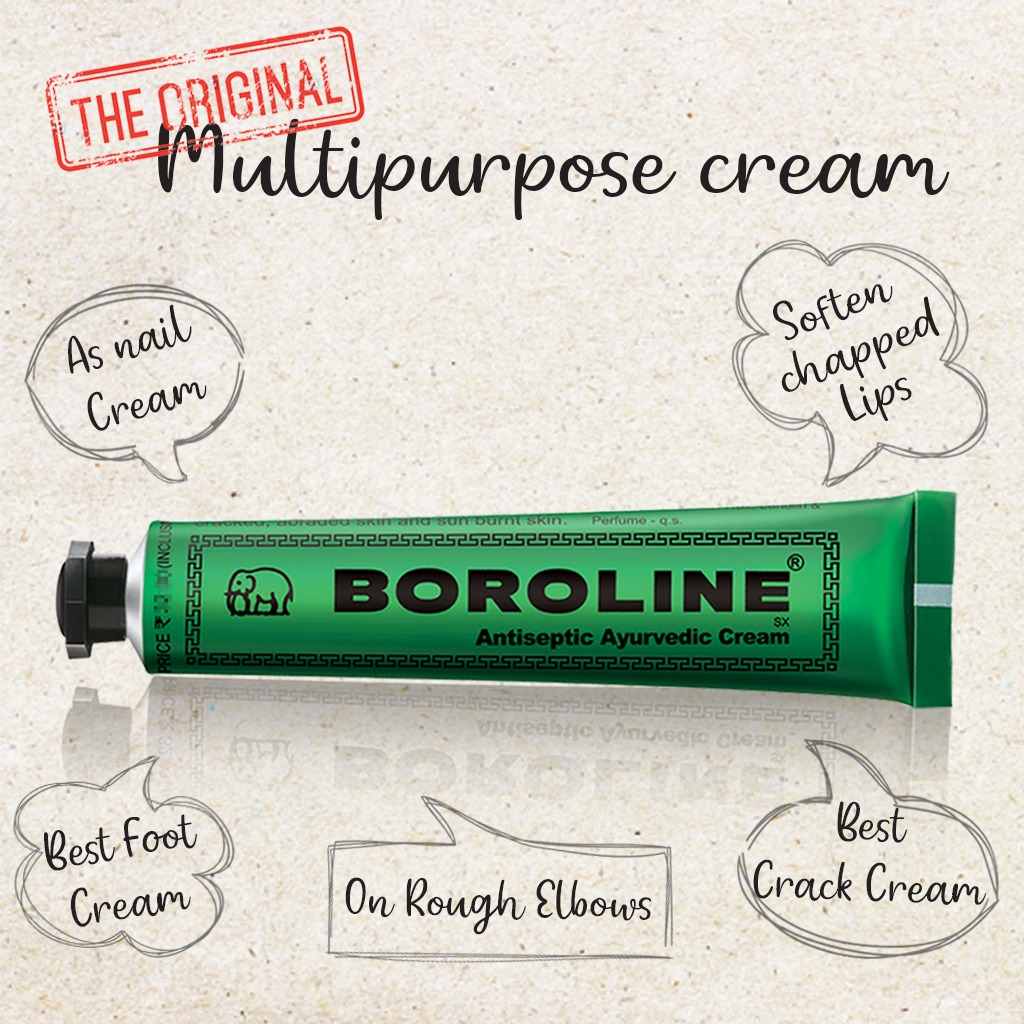

It finds its place in every home, on all travels, and as a trusted friend at work. The green tube is its timeless identity and it is virtually a panacea for all ills—chapped lips, small cuts, pimples, grazed knees, as soother or smoother… It can be found in first aid kits, home medicine cabinets, handbags, and suitcases. It is Boroline, unchanged over time, and with faithful fans across all generations.

While most of us have grown up taking its presence for granted, this unobtrusive but ubiquitous tube is more than just a cream. It is an early manifestation of the spirit of Swadeshi, and continues to be a lasting symbol of Make in India. I recently discovered this, and many facets of this comforting cream.

The non-cooperation movement against the British Rule embraced many strategies to demonstrate peaceful resistance including marches, rallies, boycott and bonfires of foreign goods. There was a demand for goods which were locally made, but not much availability of these. It was in this climate that Gourmohon Dutta, a prominent member of the business community in Calcutta decided that he would play his part in the movement against foreign goods in a different way than simply through protests. He established a company called GD Pharmaceuticals which aimed to produce high-quality medicinal products to replace similar products being imported at the time.

In 1929, GD Pharmaceuticals Pvt. Ltd began to manufacture a cream which was visualized as an ‘antiseptic cream’. The formula for this included tankan amla (boric acid) which is an antiseptic; lanolin which is a soothing agent; jasad bhasma (purified zinc oxide), which is a sun screen and astringent; paraffin; oleum (essential oils) and perfume. The cream was packaged in a green tube which had the symbol of a small elephant as its logo.

The name Boroline was derived from its ingredients: ‘Boro’ from boric powder, and ‘olin’ as a variant of the Latin word oleum, meaning oil. The logo symbolized the qualities of steadfastness and strength that an elephant stood for, as well as its auspicious significance, to bestow luck and success. It was so successful that in rural areas Boroline was known as the ‘hathiwala cream’ (cream with the elephant).

Perhaps the most ardent adherents of this cream were the Bengalis for whom the brand represented dependability and nationalism. One of the advertising radio jingles for the cream, originally in Bengali, and then adapted to Hindi, became an earworm that even today, can transport a generation to another time.

There was a brief period when, due to shortages during World War II, the cream could not be marketed in the familiar packaging, but an accompanying note reassured customers that the product was the same.

In the years leading to Independence, Boroline emerged as a symbol of resilience and self-sufficiency. A true blue swadeshi product which would go on to become an intrinsic part of households across the country, even in the decades following Independence.

By 1947 Boroline had become a household name that besides its multiple uses, stood as a symbol of patriotic entrepreneurship. As a tribute to this customer support, on India’s first Independence Day, 15 August 1947, the company is believed to have advertised that it would distribute one lakh free tubes of Boroline.

Today, almost eight decades later the swadeshi cream has its faithful followers, even under the deluge of high-end skincare products, which promise miracles. A recent piece by a young model in the fashion magazine Vogue describes Boroline as the ultimate ‘go-to’ in all situations, reinforcing the unwavering role that this cream continues to plays even today. The company has also diversified into a few other products, but none has the same kind of brand recall as Boroline.

While the basic packaging, colour and logo of this cream have not changed, its mother company GD Pharmaceuticals has moved with the times. Starting with production in a small manufacturing unit in a hamlet just outside Kolkata, and which continues to function today, there is a second facility near Ghaziabad. The factories are fully automated, and production processed are meticulously monitored. The company adheres to all mandatory government regulations and complies with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). All packaging materials used are recyclable and the waste produced is biodegradable. Just as the brand denotes integrity, the company also takes its social responsibility role seriously, and continues to be committed to serving the nation.

August is a significant month in the history of India’s freedom movement. The first Swadeshi Movement was officially launched in Bengal in 1905, on 7 August. The Quit India movement started on 8 August 1942. India became an Independent nation on 15 August 1947. This is a good time to celebrate Boroline, the swadeshi cream.

–Mamata