Not chocolates and roses. Here is a Women’s Day post that is about gore and crime.

Though not often associated with forensic science, women down the ages and across the world have played a huge role in defining it. We celebrate a few of them.

The Dollhouse Decorator

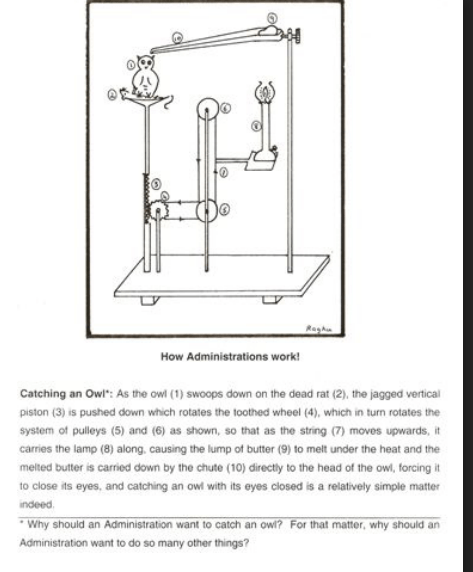

At a time when women were expected to add beautiful touches to drawing rooms, Frances Glessner Lee was building miniature crime scenes.

Often called the ‘Mother of Forensic Science’, she started recreating dollhouse-scale reconstructions of unexplained deaths in exquisite detail. This stemmed from her inherent interest in solving crimes, and inputs from a close friend who was a medical examiner, who believed that investigators often disturbed crime scenes, missed small but critical evidence and jumped to conclusions too quickly.

These “Nutshell Studies” became training tools for investigators at Harvard University. Every curtain hem, every blood spatter, every overturned chair was re-created down to the smallest detail. Trainees had to study the model for a fixed amount of time, take notes, propose the cause and manner of death, and defend their reasoning. Thousands of police personnel were trained using these tools which contributed greatly to the professionalization of forensic science

Born in 1878 to a wealthy family, she was denied a formal education in medicine simply because she was a woman. Later in life, after inheriting a substantial fortune, she used her resources to support the emerging field of forensic science at Harvard University.

The Woman in the Mass Graves

Fast forward to the 1990s.

In post-genocide landscapes in Rwanda and the Balkans, a young forensic anthropologist named Clea Koff was working with teams assisting the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

She is best known for her work investigating mass graves and gathering forensic evidence of genocide and crimes against humanity for United Nations tribunals in the 1990s and early 2000s. In Rwandashe worked in exhuming mass graves of victims from the 1994 genocide, documenting and recovering remains used as evidence in genocide prosecutions; in Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia, and Kosovoshe participated in multiple missions documenting war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Her efforts in unearthing skeletal remains, establishing identity, and collecting evidence to support criminal prosecutions helped in proving many crimes against humanity.

She is also known for her widely read memoir The Bone Woman.

The Woman Who Said, “Check Again.”

Then there is contemporary Britain.

Angela Gallop, born 1950, joined the Forensic Science Service in 1974 as a senior biologist — one of the few women in the laboratory at the time. She visited her first crime scene in 1978, investigating the murder of Helen Rytka by the Yorkshire Ripper.

She contributed decisively to many cases: in the case of Roberto Calvi, she could prove murder rather than suicide; her meticulous re-examination of microscopic blood evidence helped to identify the real criminal in the Lynette White murder; she found evidence to tie the murderer to the crimes in the Pembrokeshire Coastal Path Murders. Her work helped to re-open several cases like the Rachel Nickell murder

She was also involved in the review of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, finding no scientific support for conspiracy theories.

After her contributions to the government, she founded Forensic Alliance, an independent consultancy known for revisiting controversial cases.

She was one of the first people to warn about confirmation bias–the human tendency to decide first and prove later. Her stance was always that evidence must lead.

Thanks to her, criminals were brought to book, and maybe even more importantly, innocents were released.

And Closer Home…

Dr. Rukmani Krishnamurthy is widely recognised as India’s first woman forensic scientist.

She entered forensic science in 1974 (the same year that Angela Gallop began her career!), joining the Directorate of Forensic Science Laboratories (DFSL) in Mumbai at a time when the field was overwhelmingly male-dominated and went on to become Director of DFSL Maharashtra and later took up many senior forensic leadership roles.

Dr. Rukami Krishnamurthy

She led major forensic examinations in high-profile cases such as the 1993 Mumbai blasts, the Matunga train fire, Joshi-Abhyankar serial killings, dowry deaths, and others.

Under her leadership, forensic labs adopted advanced methods including DNA profiling, cyber forensics, and lie detection techniques. She helped transform Indian forensic practice from a peripheral support function to a central scientific pillar in criminal investigations.

Another star is Sherly Vasu, a trailblazing forensic pathologist and surgeon, known for her deep impact in medico-legal work in Kerala. She completed her MD in Forensic Medicine and became the first woman forensic surgeon in the state. She headed departments of forensic medicine at prestigious medical colleges and later served as Principal of a medical college. She has not only trained generations of forensic scientists, but has conducted around 15,000 autopsies and contributed to evidence in many criminal cases.

So this Women’s Day, let us pay homage to these women who made their mark in a very offbeat career path—bringing criminals to book. It is women like them, who quietly established that expertise is all that counts, who have paved the way for all women in all careers.

Happy Women’s Day!

–Meena