I recently read a book by Jhumpa Lahiri. She is perhaps best known for her novel The Namesake which was also made into a film. This book, titled In Other Words, is very different in that it is not fiction but rather an autobiographical work that describes the author’s determination, and process, of not just learning a new language—Italian–but writing a book directly in this acquired language. The English version is a translation (not by her) of the original in Italian.

One of the key observations and learnings from this process is the realization that every language has so many nuances that are closely linked with the culture and history of its land, that on many occasions it is almost impossible to find a satisfactory equivalent, let alone a appropriate ‘translation’ of the word. She describes her experiences of actually conversing with local people, even after having academically ‘mastered’ Italian, and the nervous jitters it caused her. It would be interesting to know if the Italians have a specific word for this feeling. Well, the Japanese do! Yoko meshi is a Japanese word that describes just this feeling!

As someone who does some basic translation I too often find that Indian languages have such a gamut of words that so aptly describe such nuances. In the English language these are often simply clubbed into a single word; a word that is unable to capture the spontaneous response or image that the word evokes in the original language.

This is true of all languages and cultures. It is great fun and invigorating to come across such words. Here is a sample from my collection!

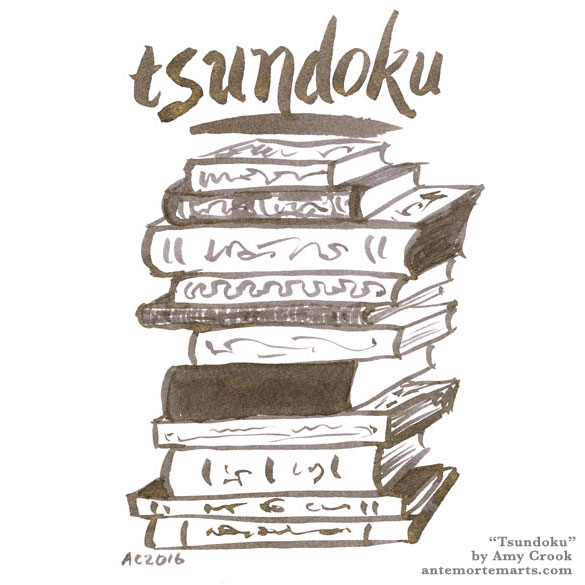

Honnomushi is the Japanese word for ‘bookworm’ and its literal translation is found in English as well as other languages. But what about the bookworms who accumulate books with all good intentions of reading them some day? Well the Japanese have a word for that too–Tsundoku.

Tsundoku. The word literally means ‘reading pile’. It derives from a combination of tsunde-oku (to let things pile up) and dokusho (to read books). It generally refers to the tendency to buy books and let them pile up around the house unread. It can also refer to the stacks themselves. The word carries no pejorative sense in Japanese. Rather it connotes a cheerful whimsy: wobbly towers of unread books, each containing an unknown world. I am happy that now my stash of books “saved for a rainy day” has a respectable name!

Aspaldiko. Besides the joy and comfort of books, it is friends that make life worth living. While there are some that we meet regularly, there are some who one cannot meet as often. Meeting an old friend after a long time has a special excitement and delight. Well the Basque people have a word exactly for that feeling. Aspaldiko. It refers to the joy of catching up with someone you haven’t seen in a long time. A perfect word to the next time one reconnects with an old friend!

Tartle. There is the aspaldiko of meeting up with that special friend. But another way of meeting up is the organized ‘class reunion’. Meeting with literally ‘old’ faces, decades after one last saw each other, has its moments of embarrassment. The face is sort of familiar but the name that matches the face eludes, at the precise moment when you meet face-to-face. More red faces when you don’t know how to introduce the same to your spouse or children. Well the Scots have just the word for this—Tartle! This sums up the embarrassment and panic you feel when you forget someone’s name before introducing them. The word even comes handy to excuse your apparent rudeness. All you need to say is “Sorry for my tartle!”

Shemomedjamo. Reunions are also an occasion to eat, drink and be merry. As the feasting continues, you know when you’re really full, but your meal is just so delicious, you can’t stop eating it. The Georgians have a word for this mixture of gluttony and gastronomic distress. Shemomedjamo. This word means, “I accidentally ate the whole thing.”

Pelinti. In the process of getting to the stage of Shemomedjamo, you reach out for that slice of freshly arrived pizza. The melted cheese is irresistible. You bite into the piece and that tanatalizing cheese immediately sticks to your palate causing sheer agony. You frantically move the piece in your mouth hoping for some relief. While this may render you temporarily speechless, in Ghana they have a word for just this moment. Pelinti! You can scream Pelinti as you move the hot food around in your mouth in a desperate attempt to cool it before swallowing.

Abbiocco. You have feasted to the point of overeating, and perhaps had occasion to scream “pelinti”. The belly is happy and the senses replete. Conversation slowly ebbs, and it’s time for the next scene in the play. Most of us know that this calls for a siesta! Well the Italians also have a perfect word for this–abbiocco, literally meaning to collapse with exhaustion, but more effectively used to denote the slothful feeling of the need to lie down after heavy eating and drinking.

Lagom. While many cultures celebrate the joys of indulgences and their languages have appropriate words to define these excesses, the Swedes are more restrained, with a more functional approach to living. And reflecting the same approach is a single word Lagom. The word describes a general contentment with the “enoughness” of what’s presented to you in the moment. Lagom means not too much and not too little. It asks us to create balance in our lives by taking everything in moderation, avoiding both excess and deprivation.

Well it’s each to their own formula of a good life! Provided that one can have brief moments of Gigil. This giggly-sounding word comes from the Tagalog language of the Philippines. Gigil as defined is more than joy, and not quite pure excitement, but somewhere in the middle of joy, excitement, and a giddy heart-warming feeling. It is such moments that keep us alive.

Have a good life!

–Mamata