Humanity spent a few years in fear of Covid. A few decades were spent in fear of AIDS. But millennia have been spent in fear of leprosy.

Leprosy is oft-mentioned in texts of yore. In Hindu mythology, it is often the result of a curse. Samba, son of Krishna and Jambavati, was cursed with the disease by his own father for constantly harassing his stepmothers (even otherwise, he seems to have been a pretty painful character). Later, when Krishna learnt that Samba was himself led into the misdemeanor by Narada, he wanted to take back the curse, but could not. Krishna advised Samba to pray to the Sun God for a cure. Samba did so—in fact, the Sun Temple at Konark and Multan (the temple does not exist and its exact location is unknown, but may have been in present-day Pakistan) are supposed to have been built by him. As a result of his devotions, he was cured.

The tale of Reunka is a fairly typical misogynistic one. She was the devoted wife of Sage Jamadagni, cursed with leprosy by her husband for a momentary lapse—for a moment being attracted to the Gandharva King. She was advised to bathe in Jogala Bhavi a nearby lake, and was cured. But sadly, when she returned home, her husband was still furious, and commanded his sons to kill her. The first four refused and were cursed by their father to die, but the fifth, Parashuram (yes, he who was an Avatar), obeyed his father. Jamadagni, pleased with Parashuram, granted him a boon. Good sense prevailed and Parashuram begged for the revival of his mother and brothers. A repentant Jamadagni is supposed to have foresworn anger, and lived happily with his wife ever after.

Leprosy also plays a key role in the Mahabharatha. Shantanu, father of Bhisma, Chitrangada and Vishitravirya came to the throne because his elder brother Devapi had leprosy. If it had not been for Shantanu’s attraction first to Ganga and then to Satyavati, the Mahabharat war may never have taken place.

Islamic and Biblical references to leprosy also abound, and Jesus is supposed to have cured the disease with his touch.

Through the ages, leprosy was feared as a curse of the Gods, and the only salvation was a boon from them. The social ostracism and rejection by friends and family was as much a suffering as the disease itself.

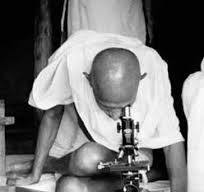

In the last few centuries, many brave souls have worked hard for the relief of these sufferings. Gandhiji was at the forefront of the fight against the fear of leprosy. Pictures of him tending to Shri Parchure Sastry, a learned man whom Gandhiji respected very much, are often seen. Sastry even made his home in Sewagram with the agreement of all the Ashram inmates.

Vinobha Bhave was another Gandhian leader who worked in this field. He and Manoharji Diwan established Kushthadham (Leprosy Centre) at Dattapur in 1936.

And of course, the selfless work of Baba Amte and his wife Sadhantai, is legendary. He was a Gandhian and active in the freedom struggle. But how he came to leprosy work is interesting. He encountered a leprosy patient one day, and it is the fear and revulsion he felt that led to deep introspection, and the decision to devote his life to this work. He not only wanted to help the patients, but also create a society free of “Mental Leprosy”, ie., the fear and misunderstandings associated with disease. He founded three ashrams for patients and devoted his life to them. The Gandhi Peace Prize and the Ramon Magsaysay award were only a few recognitions of his service.

Dr. Noshir Antia is another individual who contributed enormously to the rehabilitation of leprosy patients. He is known as the father of Plastic Surgery in India and established the first department in the country devoted to this—the Tata Department of Plastic Surgery at the J.J. Hospital in Mumbai. . His interest in this subject began when he saw the disfigurement of leprosy patients, and started to pioneer surgical techniques for correcting these. Apart from surgery, he also started research facilities to study the disease and fought against the discrimination against the sufferers of this disease, and for their rehabilitation. Dr. Antia passed away in 2007, but his legacy continues not only through the generations of doctors and surgeons trained by him, but also through the NGO he founded—the Foundation for Research in Community Health

World Leprosy Day is observed on the last Sunday of January. In India, with a slight tweak, and to mark Gandhiji’s contribution in this field, it is observed on 30 January, coinciding with his death anniversary.

The theme for the day this year is “Beat Leprosy” which calls attention to the dual objectives of the day: to eradicate the stigma associated with leprosy and to promote the dignity of people affected by the disease.

As Vinobhaji put it, the critical thing is to beat mental leprosy—the fear of leprosy. And our experience of recent diseases has shown us that fear is not the way to react to any disease. Scientific understanding and empathy are!

–Meena

Two books which may be of interest:

‘Autobiography of a Doctor’ is Noshir Antia’s tale of his life.

‘Covenant of Water’ by Verghese Abraham has leprosy, its treatment and the social discrimination as an important theme.