The last few days, newspapers have been carrying a number of pieces promoting the joy of reading physical books, in an age when the printed word is rapidly being buried under the digital avalanche. As a person who has never abandoned the physical avatars, these reminders of the very different experience of physically turning the pages of a ‘real’ book make me smile! All this hype culminated with the announcement of National Reading Day on 19 June.

I have written frequently about books, and was aware of a couple of international days of books, and reading. However this was the first time that National Reading Day was taking up so much column space. I was naturally curious to know more about this day. And I discovered that there is much more behind this day than reading. It is the story of a man with a mission, who laid the foundation of the library movement in India.

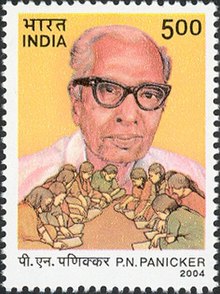

Puthuvayil Narayana Panicker was born on 1 March 1909 to Govinda Pillai and Janaki Amma at Neelamperoor in Kerala. As a youth he used to read the daily newspapers to groups of illiterate people of different ages. He began his career as a teacher, but moved beyond his designated duties to set up the Sanadanadhramam Library in 1926, in a small room provided by the local cooperative society in his village. This was the first step in what was to become beginning of a life-long passion and mission with a simple but powerful message: Vayichu Valaruku meaning Read and Grow.

Panicker held Mahatma Gandhi in very high esteem; and like him, felt that illiteracy was a curse and a shame. He believed in a holistic approach to human resources development, the foundation of which was literacy. Towards this, Panicker initiated a literacy movement across the state. He also believed that libraries could provide a stable scaffolding for encouraging and sustaining the literacy movement. He made the literacy movement into a cultural movement where people could feel the emotional connect with the library in their village or town, just as they connected with their place or worship or school or college. Libraries created by this movement later became the nerve centres of local social and cultural activities; children would come and read, older people would gather to meet and discuss issues relevant to them. When he visited a leprosy sanatorium at Nooranad, the inmates requested him to set up a library there. The library was established as LS Library on 1 July 1949. It was one of the first libraries in the district and housed a unique collection including over 25000 books and rare palm-leaf manuscripts. It was extensively used by the sanatorium residents as well as visiting researchers and scholars.

Panicker led the formation of Thiruvithaamkoor Granthsala Sangham (Travancore Library Association) in 1945 with 47 rural libraries. The slogan of the organization was Read and Grow. He travelled to Kerala villages proclaiming the value of reading and succeeded in bringing some 6000 libraries in his network. The Travancore Library Association expanded to become Kerala Granthasala Sangham (KGS) in 1956. KGS was awarded the UNESCO Nadezha K. Krupskaya Literacy Prize in 1975.

Panicker was the General Secretary of Sangham for 32 years, until 1977, when it was taken over by the State Government and it became the Kerala State Library Council.

In 1977 Panicker founded the Kerala Association for Non-formal Education and Development (KANFED) with the objective to help universalize education by stepping up propaganda for it, and by the institution of non-formal education activities supplementary to the formal education system. This led to the establishment of institutes for research and training in all aspects of non-formal education, publishing houses for the production of literacy materials, and centres for the eradication of illiteracy.

These were operationalized through Committees which were set up in all districts of the state at Block and Panchayat levels to organize, conduct and supervise literacy centres; Regional Resource Centres were set up to store books, teaching aids and other materials necessary for adult education and make them available at all literacy centres.

Primers for beginners, and books and periodicals and other useful material such a maps and wall charts for neo-literates were prepared through workshops for young writers, and published. The Primers included Alphabet Primer, Science Primer, Health Primer, as well as Primer for Women, Prier for Agriculturists, and Primer for Tribals. There were books on agriculture and animal husbandry; books on health and hygiene, and books for neo-literates. There were also biographies of inspiring national and international personalities, as well as books describing civic institutions, rights and duties, and promoting scientific temperament.

Resource material for adult literacy workers, instructors, project officers and organizers was supported and supplemented with seminars, workshops and training. Plans for monitoring and evaluation of the literacy centres were also included.

Panicker’s vision and the state-wide mission of KANFED played a significant role in Kerala’s successful literacy movement–the Sakshara Keralam Movement. The first 100 percent literate city in India, and first 100 percent literate district have been from Kerala. Kerala was also the first state to attain 100 percent primary education. Some of the oldest colleges, schools and libraries of the country are also situated in Kerala.

In addition to literacy centres, Panicker also took keen interest in promoting Agricultural Books Corners, The Friendship Village Movement (Sauhrdagramam), and Reading Programmes for Families.

The life-long crusader for literacy and libraries passed away on 19 June 1995. Since 1996, this day is marked as Vayanadinam (Reading Day) in Kerala. It is a reminder to encourage the movement to promote a culture of reading, to inculcate the habit of reading and promote book-mindedness among school children, youth as well as the underprivileged population of the country. The Department of Education, Kerala also observes Vayana Varam Week (Reading Week) from June 19 to June 25 in schools across the state.

The Department of Posts honoured PN Panicker by issuing a commemorative postage stamp on 21 June 2004.

In 2017 PM Narendra Modi declared June 19, Kerala’s Reading Day as National Reading Day in India. The following month is also observed as National Reading Month.

The PN Panicker Foundation continues the mission to enhance lives and livelihoods through various targeted initiatives ranging from education, skill development, health, and need based programmes with the efficient use of technology. In keeping with the need of the hour, it is supporting digital learning in rural areas and has established thousands of home digital libraries across the state. PN Panicker’s vision continues to guide and inspire the new generations.

–Mamata