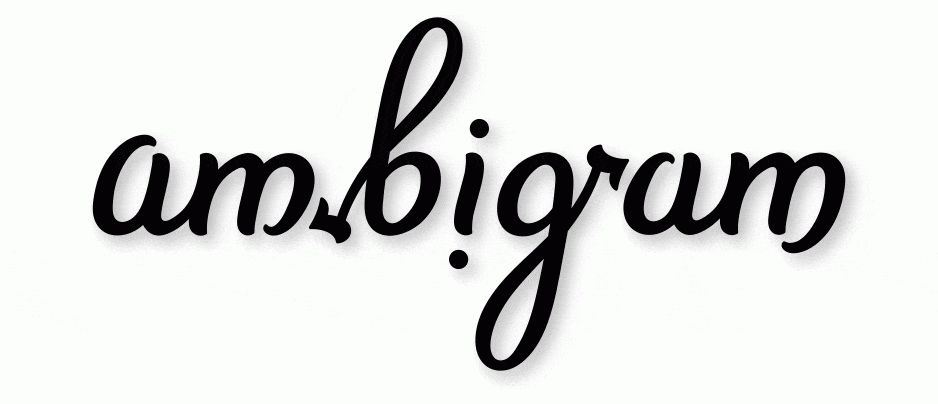

Once in a while, you come across something that makes you pause and look twice. Not because it is complicated — but because it bends the rules you thought were fixed. Ambigrams fall in that category.

An ambigram is a word or phrase designed so that it can be read in more than one way (like ‘WOW’ in the title, and the word ‘ambigram’ itself above). Sometimes you can rotate a word upside down and it still reads the same word. Sometimes a mirror reveals a hidden twin. Sometimes the letters rearrange themselves into an entirely different word depending on how you look at them. For example, bud turns into dub, while Malayalam reads the same both ways. And when turned upside down, swims reads the same, while wow turns into mom. Some ambigrams are natural (such as dollop), while others can be designed or created with calligraphy. Calligraphic ambigrams are quite popular and are often used as logos or tattoo designs.

It is typography performing a magic trick.And once you notice ambigrams, you start seeing them everywhere.

The graphic artist John Langdon’s mind-bending designs brought the form into the public eye. His work gained global attention when Dan Brown used ambigrams as visual motifs in the thriller Angels & Demons. Words like Earth, Air, Fire, and Water appeared as rotational ambigrams through artistic interpretations in the novel, sparking a wave of fascination with this unusual art form.

But ambigrams are older than that sudden burst of fame.

Some of the earliest playful experiments with reversible words appeared in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when typographers and puzzle-makers began exploring the idea that letters could be visually flexible rather than fixed. The concept was formally named “ambigram” by cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter, author of the well-known book Gödel, Escher, Bach. Hofstadter loved patterns that blurred the line between art, mathematics, and perception — and ambigrams fit that fascination perfectly.

Unlike normal typography, where letters follow strict shapes, ambigram artists must negotiate between readability and symmetry. A single letter might need to transform into another when flipped. Curves may double as stems. Serifs may become loops.

There are several kinds of ambigrams, and each works its magic differently.

Rotational ambigrams are perhaps the most famous. Rotate the word 180 degrees and it still reads correctly. Sometimes it turns into a different word. One classic example transforms “sun” into “sun” again after rotation, while more complex designs might flip “love” into “hate.”

Mirror ambigrams reveal their secret when placed beside a mirror, completing the word through reflection.

Perceptual shift ambigrams are subtler. They rely on the brain’s tendency to interpret shapes differently depending on context. A letter that looks like an “M” in one moment might suddenly become a “W” the next.

The joy of ambigrams lies in the way they invite interaction. Unlike ordinary text, which we simply read, ambigrams ask us to play. We rotate the page. Tilt our heads. Squint slightly. The moment when the hidden reading suddenly appears produces a spark of delight — a reminder that perception is not always as fixed as we think.

Creating an ambigram requires patience and experimentation. Designers sketch dozens of variations before discovering the balance where form and meaning finally align.

Interestingly, ambigrams often appear in unexpected places. Tattoo artists love them because they can encode dual meanings into a single design. Logos sometimes use them to create visual symmetry. Puzzle books and optical illusion collections frequently feature them as playful brain-teasers.

We live in a time when language moves quickly — texts, tweets, captions, headlines. Words flash past our eyes faster than we can savour them. Ambigrams slow things down. They ask us to look at words, not just read them.

They remind us that letters are shapes. That meaning can shift with perspective. That the same word can contain more than one story.

In that sense, ambigrams are more than clever design.

They are small lessons in perception.

Turn the page around, and the world might look different!

–Meena

Image source: Wiktionary