Recently there was news that a woman has been appointed as the head of the British Foreign Surveillance Agency. This is the first time in its 116 year-long history. For readers of spy fiction, and even more, fans of the popular James Bond films, this may sound as a deja-vu. After all we have such a clear image of the formidable Dame Judy Dench playing this role as M, in the fictitious MI6. In many ways the intricate workings of the MI6 and its key characters have been deeply etched in several generations of Bond followers, first through the books, and subsequently through the movies. “The name is Bond. James Bond” immediately conjures up the image of the suave but tough, risk-taking, swashbuckling, gizmo-loving hero, who has been played on screen by a series of actors starting with the inimitable Sean Connery.

James Bond: a simple name that is almost synonymous with these qualities. How did this happen? The christening of Bond is a fascinating story in itself.

The creator of this character, Ian Fleming was a British Naval Intelligence Officer during World War II. As part of his work he interacted with several spies from different countries. After the war, Fleming left the Service and decided to devote himself to writing spy novels.

He did all his writing from his winter home in Jamaica, then a British colony. He bought several acres of land and built a house mainly based on his own design. He named the house GoldenEye, named after an intelligence mission of the same name that he had overseen during his time with the Intelligence Service. This is wherehe wrote his first book Casino Royale which introduced Secret Agent 007. He named the character James Bond. This did not spring from his imagination; it was the name of an ornithologist whose books Ian Fleming, himself a birder, used to refer to while he was in Jamaica. Fleming thought that it was a perfect name for a spy as it was ‘ordinary and unromantic, but sounded masculine’. As he explained later: I was determined that my secret agent should be as anonymous a personality as possible. Even his name should be the very reverse of the kind of “Peregrine Carruthers” whom one meets in this type of fiction.

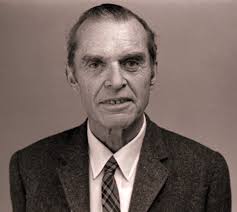

This ‘real’ James Bond was born in America but moved with his father to England when he was 14 years old, and he was educated at Harrow and Cambridge. He then returned to the United States and tried his hand at banking upon the urging of his father. But he gave this up and joined the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia as an ornithologist (self-taught). He began to focus on the birds of the Caribbean islands, undertaking long strenuous voyages on mail ships (despite being prone to seasickness), and hopping from island to island on local banana boats and tramp steamers. This is where he found his true calling. He explored the thick foliage of the islands on foot or horseback, surviving on whatever he could find. He recorded and collected bird samples. From the 1920s through the 1960s, Bond the birdman undertook more than 100 scientific expeditions to the West Indies. He collected more than 290 of the 300 bird species known to the West Indies. He wrote more than 100 scientific papers on Caribbean birds. He complied his observations in the book Birds of the West Indies. This seminal book of Caribbean bird watching was first published in 1936 and for many years remained the definitive bird watching book of the region.

It is this book that Ian Fleming, a keen bird watcher, used as a reference while he spent the winter months at GoldenEye on the north coast of Jamaica. And it is the name of the author that he gave his fictitious character. James Bond, the spy, went on to become one of the most famous names in spy fiction.

Ironically, the real James Bond did not know about this new identity for almost a decade after that. His wife found a reference to this in a magazine interview with Ian Fleming and wrote to the author. Ian Fleming admitted that he ought to have taken permission for the use of the name. To make up for this lapse, the story goes that he wrote back to ornithologist Bond with three offers: He gave Bond “unlimited use of the name Ian Fleming for any purpose he may think fit.” He suggested that Bond discover “a horrible new species” and “christen [it in] insulting fashion” as ”a way of getting back!” And he invited the Bonds to visit Goldeneye so that they could see “the shrine where the second James Bond was born.”

In 1964 the real Bonds who were in Jamaica on a research trip paid a surprise visit to Ian Fleming at GoldenEye. Ian Fleming tested his authenticity by asking Bond to identify some birds. The two went on to become good friends, although Ian Fleming died not long after.

The ornithologist and the spy, an unusual coming together. While the James Bond franchise continues to thrive and profit, it is fitting to remember the original James Bond whose pioneering contributions to the field of ornithology and conservation have laid the foundation for all that has come after. James Bond was prophetic when he wrote in his introduction to Birds of the West Indies: “In no other part of the world … are so many birds in danger of extinction.… It is to be hoped that the island authorities will show more concern for the welfare of their birds so there may yet be a possibility to save the rare species from being annihilated. Bird sanctuaries should be created where no hunting of any kind is permitted.”

On a more personal note James Bond, the spy, entered our family in the mid-1960s. My mother was recovering from an accident and in a lot of pain. Someone (perhaps a nephew) gave her a couple of Ian Fleming books to distract her. She was soon hooked! Thereafter James Bond was ensconced on our bookshelf, and both my parents enjoyed the books. I am not sure if they saw any of the Bond movies. But I know that they would have equally enjoyed this story about the real James Bond!

— Mamata