I love potatoes in all forms, from French fries to aloo tikki! I am sure that I am a member of a global club of potato fans. And worldwide it surely is, because the potato is such a versatile vegetable that it finds its place in cuisines across the globe. Used in different forms from the simply boiled and mashed to being roasted, sautéed and topped with a variety of fancy toppings, potatoes provide tasty sustenance and comfort.

Potatoes have also been generally perceived as being ‘only starch’ and children are admonished when they gorge on potatoes; and reminded that they must eat their ‘green vegetables’ that provide greater nutrition. But wait! In recent times the potato has been elevated! It is celebrated for its nutritional value as well as its role in providing food and livelihood security. It has been recognized by the United Nations for its deep historical and cultural significance, and its evolving role in today’s global agrifood systems. The United Nations has even designated a day to be observed annually as the International Day of the Potato.

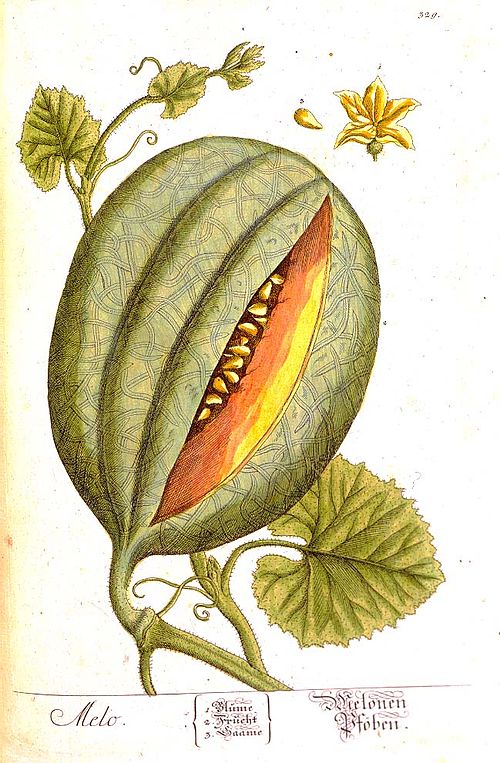

The potato traces its roots way back to the Andes where it originated, and was domesticated during the Inca civilization and was revered as ‘the flower of ancient Indian civilization’. Following domestication, these early potatoes spread through Mesoamerica and became a crucial food supply for indigenous communities. It was particularly suitable as a staple foodstuff called chuño, a freeze-dried potato product that could last years or even decades.

The Spanish invasions of the mid-1550s dwelt a blow to the Inca Empire, but gave a new lifeline to the potato. The invaders took tubers across the Atlantic, as they did with other crops such as tomatoes, avocados and corn, in what historians call the Great Columbian Exchange. For the first time in history, the potato ventured beyond the Americas; and gradually established itself on the European continent. These tubers, first grown in Spain were then sent around Europe as exotic gifts to botanists, and even prominent figures like the Pope. The potato played a role in the rise of urbanization and fueled the Industrial Revolution. By the end of the 18th century, potatoes had become in much of Europe what they were in the Andes—a staple.

The potato also gained popularity with sailors as it provided nourishment during long voyages. It is likely that these staples spread widely across the world through these voyages, taking root on different continents. In fact the potato has been called the “world’s most successful immigrant”, as its origin has become unrecognisable for producers and consumers everywhere.

Since then, the potato has shaped civilizations and diets across continents over several centuries. Ireland’s Great Famine of the 1840s was caused by the failure of the potato crop due to a fungal disease. More than half the Irish population depended entirely on potatoes for nourishment, and the wiping out of the crop led to starvation or famine-related deaths of millions, while millions emigrated to escape this. On the other hand, it was the potato that alleviated famine in China during the Qing Dynasty, securing its place as an essential crop. During World War II and subsequent conflicts, the potatoes high yield and resilience provided food security amongst shortages of other food.

Today potatoes are a key crop across diverse farming systems globally, ranging from smallholders producing diverse local varieties in the Andes, to vast commercial, mechanised farms in different continents. The potato is the world’s fourth-most important crop after rice, wheat and maize, and among the first non-grains. China, India, Russia and Ukraine are among the world’s top potato producers. About two-third of the world population consumes potatoes as its staple food.

In the light of its global reach and popularity the United Nations also felt that it was important to highlight the important role of potatoes in contributing to food security and nutrition, as well as livelihoods and employment for people in rural and urban areas the world over.

Small-scale and family farming production of the potato, particularly by rural farmers, including women farmers, supports efforts to reduce hunger, malnutrition and poverty, and achieve food security, and relies on and contributes greatly to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.

Potatoes are not just a staple food but a symbol of resilience and adaptability. The potato is resistant to drought, cold, and barren land with wide adaptability. The crop’s versatility and ability to grow in a variety of conditions make it an advantageous crop choice. Potatoes provide accessible and nutritious food and improved livelihoods in rural and other areas where natural resources, especially arable land and water are limited and inputs expensive. Potatoes are also a climate-friendly crop, as they produce low levels of greenhouse gas emissions in comparison to other crops.

In addition, there is a wide spectrum of diversity among potatoes. This provides wide genetic variation with a range of traits, including the ability to adapt to different production environments, resistance to pests and diseases, and different tuber characteristics. There are efforts to preserve indigenous knowledge and ancient technologies, while ensuring that the production of native varieties remains under local control. The 12 000-hectare potato park located in the Andes near Cusco, Peru is one of the few conservation initiatives in which local communities are managing and protecting their potato genetic resources and traditional knowledge of cultivation, plant protection and breeding.

In order to acknowledge and honour the multiple contributions of the potato, and propelled by an initiative from Peru and the Group of Latin American and Caribbean countries, the United Nations designated 2008 as the International Year of the Potato. The objective was to raise the profile of this globally important food crop and commodity, giving emphasis to its biological and nutritional attributes, and thus promoting its production, processing, consumption, marketing and trade. In addition to being a food staple, potato by products are also being explored.Potato starch is being used as a sustainable alternative to traditional plastics. These materials based on potato proteins and starch can be used for various environmentally-friendly packaging, like food containers and medicine capsules.

In order to sustain the momentum, the United Nations decided, in 2024, to mark 30 May every year as the International Day of the Potato. The day highlights the importance of the crop in the movement towards sustainable development while celebrating the cultural and culinary dimensions of the crop’s cultivation and consumption.

Nutritionists say that potatoes contain nearly every important vitamin and nutrient, except vitamins A and D, making their life-supporting properties unrivalled by any other single crop. Keep their skin and add some dairy, which provides the two missing vitamins, and you have a healthy human diet staple.

So let us join the celebration this year with guilt-free indulgence of our favourite potato dish!

–Mamata