A recent weekend spent with a toddler revived the memories and joys of crayons. While playthings and pastimes have changed considerably, especially in this digital age, there are some that continue to retain their charm. Crayons are among these.

Opening a fresh box of these colourful sticks neatly lined up with their wrappers, has been a special feeling, over generations. The distinctive smell from the paraffin used in their making, equally triggers memories, long after childhood. According to a Yale University study the scent of Crayola crayons is among the 20 most recognizable scents to American adults; coffee and peanut butter are numbers 1 and 2!

The attractive colours and the smell almost triggers an urge to bite into one. And, certainly, most toddlers are often more interested in tasting the colours, rather than drawing with them!

What makes crayon? A crayon (or wax pastel) is a stick of pigmented wax used for writing or drawing. Wax crayons differ from pastels, in which the pigment is mixed with a dry binder such as gum arabic, and from oil pastels, where the binder is a mixture of wax and oil.

While these wax sticks as we know them date back a few hundred years, the technique of using wax with colours was a method known to Ancient Egyptians who combined hot beeswax with coloured pigment to fix colour into stone. Ancient Greeks and Romans used wax, tar and pigment to decorate ship bows and for drawing. The first crayons, used for marking, appeared in Europe, and were made with charcoal and oil, and hence were in a single colour—black.

Crayons in their more recognizable form were invented in the United States in 1903. They were developed by a company called Binney and Smith who were originally manufacturers of red iron oxide for painting barns and lamp black which had a number of applications including making rubber tyres black.

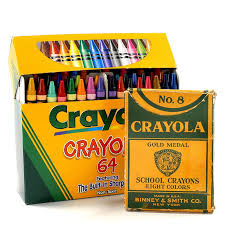

In the early 1900s the company moved on to making marking crayons for commercial use. These were used as waterproof markers in factories but they contained toxic substances and were not suitable to be used by children. The company then entered into the school market with slate school pencils and dustless chalk. Here they saw that there was potential for the use of colouring tools for educational use in the classroom. Based on feedback from schoolteachers Edwin Binney and his wife Alice developed wax crayons. They mixed waxes, talcs and pigments to form non-toxic sticks which were wrapped in paper, making these safe and mess-free. They put these on the market in 1903 under the brand name Crayola. The name was created by Alice as a blend of craie, the French word for chalk and ola from oleaginous (oily paraffin wax). Ola was also a popular ending for products at that time. The first boxes had 8 coloured crayons (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, black, and brown), and sold for 5 cents, in yellow-and-green boxes which were labelled ‘school crayons’. For the next 45 years, the colour mix and the colour names remained unchanged.

While later many companies began manufacturing crayons, the word Crayola became synonymous with crayons and continues to be so to this day.

For the first forty years, each Crayola crayon was hand-rolled in paper wrappers with distinctive labels and names. Automated wrapping started only in the 1940s. Over the next hundred years Crayola introduced packs of 16, 24, 32, 48, 64, and 96 crayons. There have been over 400 Crayola colours created since the crayons were launched. The company now manufactures 120 standard crayon colours. In addition, there are specialty crayons like metallic, gel and glitter crayons.

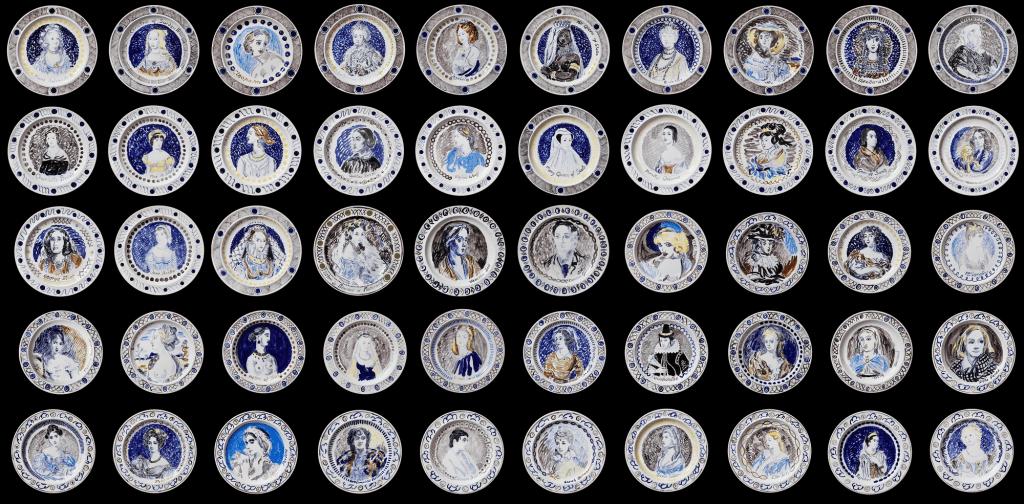

The history of naming the colours is a reflection of the changing times and perceptions. While the set of 8 colours remained unchanged for the first 45 years, by 1949, with 48 colours in the box, the palette included colours with more imaginative name such as thistle, periwinkle, carnation pink, bittersweet, cornflower, melon, salmon, and spring green. With the addition of new crayons taking the number up to 64 the colours included Copper, Plum, Lavender, Mulberry, Burnt Orange, and Aquamarine. The psychedelic spirit of the 1970s was reflected with the addition, in 1972, of fluorescent colours: Chartreuse, Ultra Blue, Ultra Orange, Ultra Red, Hot Magenta, Ultra Green, Ultra Pink, and Ultra Yellow.

The 1990s saw the retirement of eight old shades and their replacement with new ones–Cerulean, Vivid Tangerine, Jungle Green, Fuchsia, Dandelion, Teal Blue, Royal Purple, and Wild Strawberry. The decade also reflected the response to cultural sensitivities. In 1999, the name Indian Red was changed to Chestnut because educators believed that children would think the name represented the skin colour of American Indians rather than the reddish-brown pigment found near India.

In 1993, to mark its 90th birthday Crayola invited the public to name 16 new Crayola crayon colours. Some of the winning suggestions included Asparagus, Macaroni and Cheese, Timber Wolf, Cerise, Mauvellous, Tropical rainforest, Denim. Pacific Blue. Granny Smith Apple, Shamrock, Purple Mountains Majesty, Tickle Me Pink, Wisteria and Razzmatazz. The last name was the suggestion of 5 year-old Laura Bartolomei, who was declared the younger Crayola colour winner.

In 2000 Crayola’s first online consumer poll to name the favourite Crayola colour was held. Blue emerged as the all-time favourite, and six shades of blue made up the list of top ten colours!

Crayola marked its 100th anniversary by once again inviting crayon users to contribute names. With increasing diversity in schools and growing awareness of being ‘politically correct’, in 2020 Crayola introduced a new line of 24 colours named Colors of the World to reflect the multicultural skin tones of people around the world.

Thus Crayola remained on top of the game by always being dynamic, responsive, and participatory to reflect the signs of the times, as it were. Crayola continues to be synonymous with crayons, not only in the USA, but now across the world. I remember when we were children, and our local palette limited to the standard box of 12 colours from Camel or Camlin, our great dream was to be gifted with multi-layered jumbo box of Crayola crayons by a relative coming from the USA!

Today perhaps the choices of art materials and techniques have increased, but the fascination with crayons certainly has not decreased! There are Crayola crayon collectors who are always searching for samples of rare or discontinued colour pieces. And America celebrates National Crayon Day on 31 March every year, to celebrate the colourful history of these simple sticks that have provided generations of children with hours of creative fun.

–Mamata