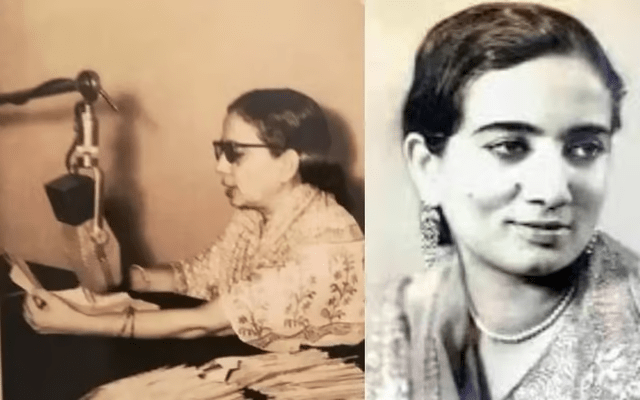

Last week I wrote about All India Radio, the voice of the nation after India gained Independence. I also wrote about some of the newsreaders who literally gave voice to the news. The early decades were remembered by names that became synonymous with different programmes broadcast by AIR, including some well-loved women voices. Before them all, was Saeeda Bano, who was the first woman to read the news on AIR. A woman ahead of her times in more ways than one.

Saeeda Bano was born in Bhopal in 1913. It was the period of British rule in India but local rulers still held sway in the numerous feudal kingdoms that made up India. Bhopal was unique in that it was a city that had been ruled by women (Nawab Begums) for four generations as there had been no male heirs to the throne. It was an unusually liberal environment where women’s education was encouraged and the hold of patriarchy was not as strong. When Saeeda was born, the last of the four Nawab Begums, Begum Sultan Jahan, a great reformer, was ruling Bhopal. She was very keen that women be educated and thereby be able to come out of the darkness of ignorance.

Saeeda’s father was supportive of the idea that girls should get as best a formal education as was possible at that time. Saeeda was sent to boarding school in Lucknow in 1925, and went on to do her graduation from Isabella Thoburn College in Lucknow. But that was as far as her family would allow. In spite of her fervent pleas, she was married off, still in her teens, to a highly-respected judge in Lucknow who was many years older. The plunge into a highly-confining world, shackled by social expectations and dos and don’ts was stifling to the lively young girl who was at all times expected to play the role of a dutiful wife, and adhere to repressive norms. However she stuck it out for almost 20 years, playing the role of wife and then mother to two sons, even as the stirrings of rebellion built up. In 1938 when a radio station was set up in Lucknow, Saeeda started participating in shows for women and children. As her domestic life became more turbulent, Saeeda began looking for a way out. She sent her application to what was then still BBC in Delhi for the post of newsreader. The application was accepted. This was the impetus that propelled her to leave her husband’s house and her husband, and move to Delhi. She put her older son in boarding school and arrived in Delhi with her younger son. She was alone, in a new city, about to make a new life for herself.

Saeeda and her son arrived in Delhi on 10 August 1947, and stayed with some family friends. She reported to All India Radio the next day, met the Director of news, and spent the entire day getting familiar with the premises and the world of broadcasting. The following day when she reported for work at the radio station, a weekly roster of her duties and timings had been prepared and was handed over to her. She was to reach AIR on the 13th of August 1947 by 6 am and read the news bulletin in Urdu at 8 o’clock thereby becoming the ‘first female voice, news anchor of All India Radio’s Urdu news bulletins’.

As she recalled in her memoir: I was the first woman AIR considered good enough to read radio news. Prior to this, no woman had been employed by either the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) or AIR Delhi to work as a news broadcaster. Of course they had to train me and I was taught how to first introduce myself on air with my name and then start reading the bulletin.

Thus Saeeda Bano became the first woman newsreader on All India Radio, two days before India gained Independence. She was proud to be a member of the AIR team that broadcast, live, to the nation, the momentous transition of power.

While she broke barriers in broadcasting, Saeeda continued to face challenges as a single woman in a big city. She looked for accommodation, and moved to YMCA, after a struggle to obtain special permission to keep her son with her. Saeeda Bano grew with her job and went on to research and anchor other programmes also. But it was not all smooth sailing.

The dawn of Independence also unleashed the fury of violence in the aftermath of Partition. As a Muslim woman whose voice was becoming heard and known, she was the target of hate mail and threats. She was forced into taking refuge with other Muslim personalities of the time, and was witness to many distressing situations.

Perhaps the most distressing event that left a deep impression on her was the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. Saeeda Bano had in fact been to Birla House to listen to Gandhiji in person, on the very day that he was killed. She later wrote how she had felt a note of despair in his voice. The shock of his death was so great that she was unable to read the news that day, and the news director had to hurriedly change the shifts.

Saeeda Bano’s in-built reliance and ability to face challenges remained with her through her life. She retired as news reader from AIR in 1965, and was appointed as producer for AIR’s Urdu Service and continued till the 1970s. She passed away in 2001.

Saeeda Bano’s achievements are much greater than her ‘first’ as a newsreader. In 1994 she wrote her memoir Dagar Se Hat Kar in Urdu where she described the ups and downs of her life, candidly and without bitterness nor self-praise. She simply described herself as one of those people who “chose a road less travelled“. The book was translated into English by her granddaughter Shahana Raza and published in 2020 as Off the Beaten Track: The Story of my Unconventional Life.

Remembering her grandmother, Shahana described how Saeeda Bano or Bibi as she was affectionately called, was a woman who lived life on her own terms. She lived independently, and didn’t seek support from anyone, even in the lowest phases of her life. Her sheer determination always stood out, as she never looked back and regretted any of her decisions.

Today as so many women confidently anchor news and other shows, especially on the numerous television channels, they face their own challenges and new glass ceilings to break. But it is always humbling to remember and celebrate those who took the first steps in clearing untrodden paths.

–Mamata