What can one say about the year that is winding to a close? Sadly, despite many stories of achievements and accomplishments across the world, and even into space, perhaps the images that will haunt us the most will be those of the ravages of war. A frightening reminder of human’s inhumanity to humans. While the voices of the war-mongers are louder and more strident, there are, in every time and generation a few who gently, but passionately, fight the non-violent battles for peace.

One among these was Daisaku Ikeda, the Buddhist philosopher, educator, author, poet, and above all, peace-builder. Ikeda was born in Tokyo, Japan, on January 2, 1928, the fifth of eight children, to a family of seaweed farmers. He grew up in a period when Japan was in an authoritarian and militaristic phase of expansion, and heading towards World War II. As a teenager Ikeda was witness to the devastation and suffering of the war, including the death of his elder brother in action. The young Ikeda was deeply disturbed by the seemingly meaningless human conflict.

At the age of 19, Ikeda met Josei Tado, an educator, pacifist and leader of the Soka Gakka, a Japanese Buddhist religious movement based on the teachings of the 13th-century Japanese priest Nichiren. Toda had been imprisoned during the war together with his mentor Tsunesaburo Makiguchi. Both had held firm to their religious convictions in the face of oppression by the military authorities who had imposed the Shinto ideology as a means of sanctifying their war of aggression. Makiguchi had died in prison, and Toda had resolved to stand up to the militarist regime. This greatly impressed Ikeda who was drawn to the Buddhist philosophy of peace and non-violence. The seeds of Ikeda’s passion for peace were firmly sown.

Toda was engaged in the process of rebuilding the Soka Gakkai which had been all but destroyed as a result of wartime persecution. The young Ikeda shared Toda’s conviction that the philosophy of Nichiren Buddhism, with its focus on the limitless potential of the individual, cultivated through an inner-directed revolution, could help revive society in the devastation of post-war Japan.

Ikeda accepted Toda as his mentor, and the next ten years became as he described, ‘the defining experience of his life and the source of everything he later did and became.’ Toda died in 1958, and in May 1960, Ikeda succeeded him as president of the Soka Gakkai. He was 32 years old. In 1975, Ikeda became the founding president of Soka Gakkai International (SGI), which grew into a global network that brings people of goodwill and conscience together. Under his leadership, the movement began an era of innovation and expansion, becoming actively engaged in initiatives promoting peace, culture, human rights, sustainability and education worldwide. He established the Soka (value-creation) schools system, a non-denominational educational system based on an ideal of fostering each student’s unique creative potential and cultivating an ethos of peace, social contribution and global citizenship.

Ikeda’s philosophy is grounded in Buddhist humanism; the central value being the fundamental dignity of life, which is the key to lasting peace and human happiness. In his view, global peace relies ultimately on a self-directed transformation within the life of the individual, rather than on societal or structural reforms alone.

From a healed, peaceful heart, humility is born; from humility, a willingness to listen to others is born; from a willingness to listen to others, mutual understanding is born; and from mutual understanding, a peaceful society will be born. Nonviolence is the highest form of humility; it is supreme courage.

Ikeda also firmly believed that the foundation of peace lay in dialogue. Dialogue and education for peace can help free our hearts from the impulse toward intolerance and the rejection of others. People need to be made conscious of a very simple reality: we have no choice but to share this planet, this small blue sphere floating in the vast reaches of space, with all of our fellow “passengers.”

Dialogue and the promotion of cultural exchange became the basis of his efforts to build trust and foster friendship in contexts of historical division and conflict. In order to discover common ground and identify ways of tackling the complex problems facing humanity, Ikeda pursued dialogue with individuals from diverse backgrounds—prominent figures from around the world in the humanities, politics, faith traditions, culture, education and various academic fields. Over 80 of these dialogues have been published in book form. Through his writings and actions Ikeda became a pioneering practitioner of the concept of ‘a culture of peace’.

Ikeda also founded a number of independent, non-profit research institutes to promote peace through cross-cultural, interdisciplinary collaboration: the Boston Research Center for the 21st Century (renamed Ikeda Center for Peace, Learning, and Dialogue in 2009), the Toda Institute for Global Peace and Policy Research (renamed Toda Peace Institute in 2017) and the Institute of Oriental Philosophy. The Min-On Concert Association and the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum promote mutual understanding and friendship between different cultures through the arts.

Ikeda was a multi-faceted personality—philosopher, educator, writer and peace-builder. But all his endeavours were rooted in his strong faith in the positive potential inherent in the life of every person. Ikeda was convinced that peace is ultimately inseparable from enabling the flourishing of each person’s individuality. A great inner revolution in just a single individual will help achieve a change in the destiny of a nation and, further, will enable a change in the destiny of all humankind.

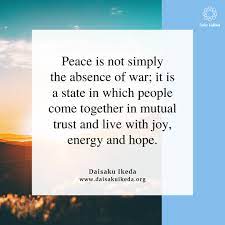

For Ikeda, peace was far more than the mere absence of war. He saw this as a set of conditions in which cultural differences are embraced and appreciated and in which dialogue is firmly established as the means of choice for resolving conflict. In the end, peace will not be realized by politicians signing treaties. True and lasting peace will only be realized by forging life-to-life bonds of trust and friendship among the world’s people. Human solidarity is built by opening our hearts to each other. This is the power of dialogue.

Daisaku Ikeda passed away on 18 November 2023, at the age of 95 years. As another war rages on, the world is in dire need of the wisdom of men such as him, to remind us again and again of the futility of violence. Peace is not simply the absence of war; it is a state in which people come together in mutual trust and live with joy, energy and hope. This is the polar opposite of war―where people live plagued by hatred and the fear of death.

With hope and a prayer that the year ahead may lead humanity from war to peace.

Peace is not found somewhere far away. Peace is found where there is caring. Peace is found when you bring joy to your mother instead of suffering. Peace is found when you reach out and make an effort to understand and embrace someone who is different from you. Daisaku Ikeda

–Mamata